The year is 1977 when Boogie Nights (New Line) begins. Eddie Adams is a 17-year old busboy in a San Fernando Valley nightclub when he is spotted by Jack Horner, a director of porno films. Horner, with the intuition that made him wealthy, senses potency and potential in Eddie. He quickly learns that Eddie has already earned some money sexually, so little persuasion is needed. Horner soon makes Eddie into a big porno star, under the name Dirk Diggler.

For us, however, he remains, most of the time, Eddie, a basically sweet naif, doing what is asked of him sexually like an obliging peasant youth in Sade, except that he becomes mildly famous and well-off. His new life, brings along many new people. First, there is Horner’s girlfriend, a porno star called Amber Waves—in fact, she is Eddie’s first on-camera lay. Then there is Rollergirl, a porno playmate who doesn’t take off her rollerskates for sex. And there is a large miscellany of others in and around the business, almost all of them druggies.

Some of the group’s stories are tracked through the screenplay, with or without Eddie’s involvement, much as was done in Nashville or Pulp Fiction. This braiding device entails a bit of padding; still, as the film blasts along from 1977 to 1983, it cracks open its world. The finish fits out most of the strands with relatively pleasant conclusions. Only the ending of Eddie’s story is a touch too neat. (And, too, there are a couple of murders along the way that the picture simply shrugs off).

Boogie Nights was written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. This is remarkable. Anderson’s only previous film, Hard Eight, was one of those strained independent films whose threadbare central idea wears out very soon. With Boogie Nights, Anderson may have had help from the people who are always around an expensive production, but it has the temper of one person’s ingenuity and energy. It’s an extraordinary step forward from his first picture—a 152-minute film with almost no sags.

All this in spite of the fact that Anderson never quite achieves his presumable chief aim. This picture moves us into a terrain where the moral scale is unabashedly different from the rest of the world’s, even the part that patronizes porn, and it asks us to accept that scale: its ambitions, judgments, loyalties, even its annual “Oscars.” This acceptance never quite happens for us. When a porno production man finally kills his wife, who has frequently coupled with other men in public, and then kills himself, it’s hard to feel the pathos that’s intended. Why didn’t he shoot her before? Or why did he bother now?

Wlien Amber, a divorcee, goes to law for visitation rights with her son and loses, her heartache doesn’t quite reach us. Who would want a child to spend much time in her environment? Yet, despite the film’s distance from us, we are held. In part, of course, there’s the sexual titillation: whether or not we’re sated with porn, the way that those films are made still catches us. Mostly, however, our interest seems to connect with a shift in standards. Moral criteria have been replaced by stylistic ones.

To put it another way, if Boogie Nights were poorly made and acted, its materials would make it intolerably tawdry. But it’s so well done that we keep watching. Film historians may already be at their computers, tapping away at this transition from the sin-suffer-repent of the past to the contemporary acceptance of almost anything if it’s sufficiently well made. Of course there have been precedents in other arts for centuries. (Why is Courbet’s The Origin of the World, a depersonalized closeup of female genitalia, hung in a museum instead of being copied and sold with Hustler? Because it’s beautifully painted.) Now this license through quality reaches the most widely seen art on earth. What does this transition imply or—dread word—forebode? Tune in next century.

As is, Boogie Nights dazzles along. Two scenes stand out memorably. After Amber loses her plea for her son, she is in her lush bedroom talking with Rollergirl, who has problems of her own. The younger one, in tears, says she needs a mom, and the older one (not that old) hugs her as they cry and nestle together. The suggestions in this well-written scene are subtle and evocative. And there’s a long scene toward the end where Eddie, temporarily in money trouble, takes part in a drug delivery and robbery. The place is the home of the rich Rahad Jackson, who is on a giggling high throughout, in his briefs and open robe. The scene is punctuated by the firecrackers that his Chinese companion keeps setting off; and the inevitably bloody outcome hovers invisibly in the air waiting to materialize. The whole scene plays like an insane ballet.

Anderson directs throughout with verve and fluency. His very enthusiasm spurs his talent to carry him over dangers. For instance, the several wild parties. Little is deader on screen than most wild parties, but Anderson makes them smooth, hip bacchanals, with variegated people winding through on their hedonistic way.

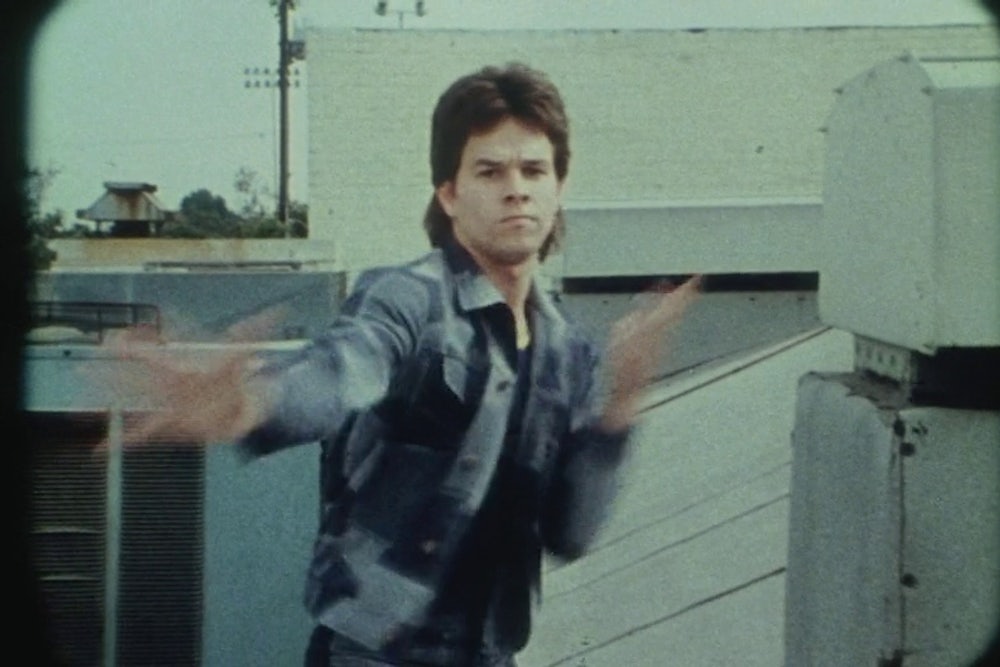

His ability, always clear, is at its clearest in his casting and directing of actors. Mark Wahlberg gives Eddie the precise note of unvicious amorality. (At the end we glimpse the reason for Eddie’s success—his prodigious organ. At least we are to believe it’s his.) Burt Reynolds seems to have invested his whole career in preparation for Jack Horner. Ease used as ethic, a seriousness that is meant to be transparent, all the qualities that marked his unctuously inveigling performances lead directly to Jack, a man of a dependability that is limited only by self interest, with an embrace that is part smother.

Julianne Moore, already distinguished not only by her gifts but by her daring choice of roles, is rightly regal as Amber. She is the queen of herself, moving through her life with the assurance of hermetically sealed values. Heather Graham, the Rollergirl, is pleasant as a human Barbie doll. Every other part, large or lesser, is cast precisely and taken to its utmost. A particular salute to the English actor, Alfred Molina, as Rahad, a carefully designed frenetic performance.

Three more salutes. Robert Elswit gets right to the texture of scene after scene, and thus gives the film itself a seductive luridness. Dylan Tichenor, the editor, knows exactly what we want to be looking at, a moment before we know it ourselves. And the music, old and new, tended by Michael Penn, is a jet propulsion under it all.