One

year after Joe Biden’s inauguration, Amanda Gorman recounted how she almost didn’t read her luminous poem,

“The Hill We Climb,” at the ceremony that day, how she overcame fear—of failure,

Covid, and violence in the wake of the Capitol riot—by listening to the greater

fear of forever wondering what “the poem could have achieved.” A year is a tiny

vantage point from which to reflect on the possible effects of our words. The

words of those further in the past are still doing work now, as historians keep

them before us, in endlessly new garb, so that history keeps making history.

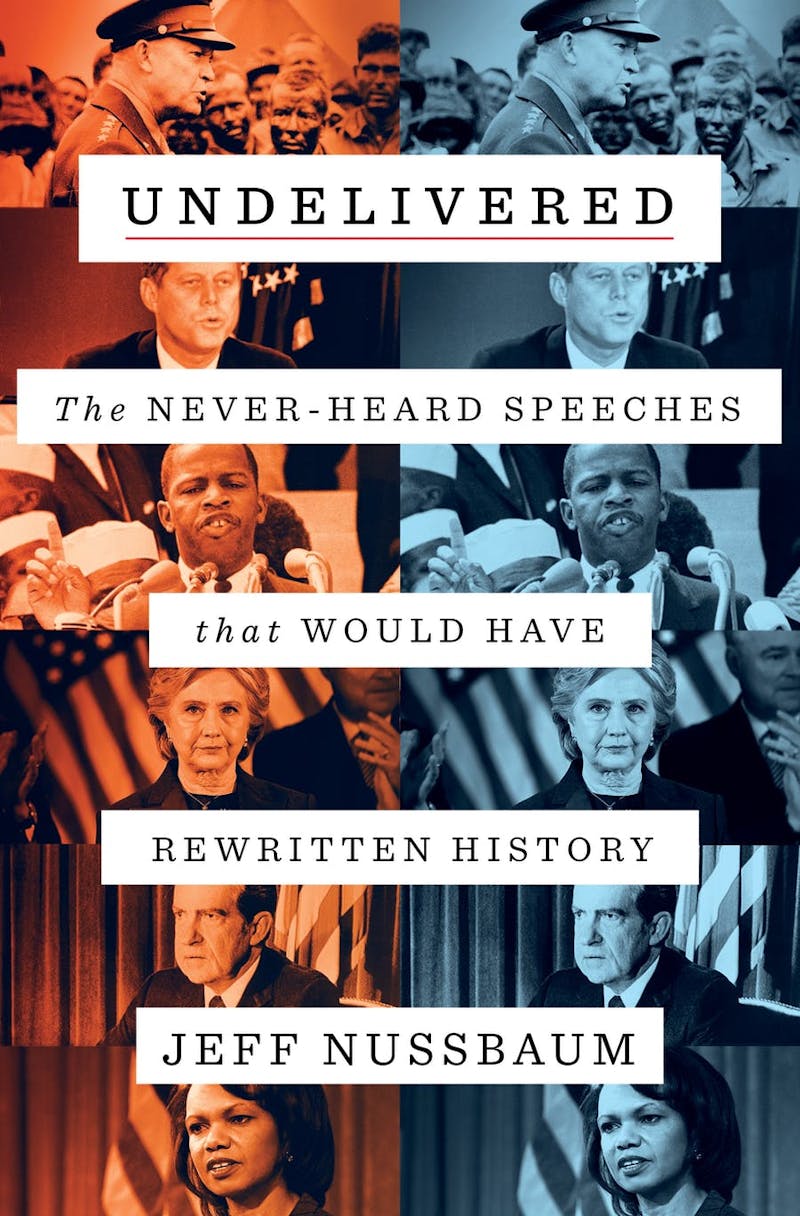

Like poetry, the political speech is a traditionally oral form whose influence proliferates through reproduction in print and other media. In Undelivered, Jeff Nussbaum, speechwriter for powerful politicians, including then–Vice President Joe Biden, tells the stories of speeches that never made history because events prevented their delivery—often happily, at times unhappily. Many are tied to momentous historical events, such as the D-Day landings, the abdication of Edward VIII, Nixon’s resignation, and the March on Washington. He includes the victory speech Hillary Clinton planned to deliver in 2016 and the speech urging missile defense that Condoleezza Rice would have given on September 11, 2001—the very day the United States proved vulnerable to a low-tech terrorist attack.

Alongside speeches linked to such pivotal events are those that might have created major turning points had they been delivered, such as the indictment of the super-rich that Emma Goldman suddenly decided not to deliver at her sentencing in 1893 or the speech against fascism that death prevented Pope Pius XI from giving in 1939. The speakers are monarchs and presidents, Native and African American leaders, anarchists and the disabled. While unlocking the universe of historical possibility, Nussbaum remains attentive to his stories’ human dimensions and the internal commotion that accompanies a stymied speech. Entangled with these riveting accounts is the history and anatomy of the political speech as a genre and of professional speechwriting and its peculiar self-effacing power: the speechwriter as witness to and author of great events.

The unifying premise of Undelivered is to highlight the central role of speeches in the making of history and the glimpses they offer of alternative worlds we might inhabit. Outcomes that seem certain in hindsight were in fact precarious at the time, these never-given speeches suggest. What if John Lewis had given a different speech at the March on Washington? What if Helen Keller had been able to make her speech in the Suffrage Parade of 1913? How would our world be different?

The

hitch, however, is that some undelivered speeches turn out to have been simply

undeliverable or never intended for delivery, making it difficult to imagine

them as keys to alternative worlds. Crucially, they often went undelivered in

the face of the more irresistible historical power of the collective, forged

through everyday exchanges—which may be the speech that matters most.

It’s easier to conceive “an alternative history” in some cases than in others. Certainly we can imagine Warren Beatty receiving the right envelope at the 2017 Academy Awards, so that Barry Jenkins could give his speech in acceptance of the best picture award for Moonlight. (Instead Beatty congratulated La La Land, and Jenkins’s words, aimed at inspiring dreams of possibility in young people, went undelivered.) It’s harder to imagine John Lewis giving the original, militant draft of his speech rejecting the civil rights bill and denouncing patience at the March on Washington—a speech that would have alienated key audiences and changed the course of the civil rights movement, Nussbaum argues. But it is difficult to see from Nussbaum’s own account how Lewis could have delivered it, given his earnest commitment to a collective endeavor, for which he knew he had to accommodate his personal preference to fellow organizers’ priorities. The speech was undeliverable in the circumstances.

Likewise, it’s difficult to believe that a single speech might have swayed Britain toward fascism in World War II. In 1936, King Edward VIII—a monarch sympathetic to the Nazis—was forced to abdicate in order to marry the divorcée Wallis Simpson. Egged on by Winston Churchill, he considered appealing to the public to avoid this fate, and Nussbaum includes the text he drafted. But in a constitutional monarchy, he would have needed ministerial approval to make such an appeal. His toying with an address was just that—toying. He may have thought that the British people would support his appeal, but he lacked the power to make it. Moreover, even Edward’s successful evasion of abdication would not have put Britain “fully on the side of fascism” in the war. He was hardly unique among Britain’s political elite in admiring Hitler in 1937. Churchill sided with the fascists in the Spanish Civil War, and his 1937 book, Great Contemporaries, included a friendly chapter on Hitler. Fascism became a problem for him only when it fueled German expansion in Europe. In missing this, Nussbaum succumbs to the spell of Churchill’s epochal speeches of 1940. It’s entirely likely that a King Edward in power in 1939 would have heeded the ascendant ministerial view; his views as an abdicated king desperate to “distinguish” himself aren’t a reliable guide to what he would have done as king.

The speeches that most intriguingly compel reflection on the premise of counterfactual history are those written purely to ensure against the need to deliver them. Dwight Eisenhower habitually drafted apology speeches before amphibious operations for good luck. His undelivered apology for D-Day’s failure may count as an undelivered speech—if we don’t share his superstition that his very writing of it obviated its delivery. Such stories ask us to take measure of whether we believe otherworldly forces play a part in history. (Certainly, the Clinton campaign’s “karmic reasons” for crafting a concession speech did not have the hoped-for auspicious effect.)

It’s not merely whether but how a speech is delivered that determines its effect—the performance, quite apart from the text. Nussbaum’s sensitivity to this reality, however, stirs a sense of history’s sublime open-endedness rather than a vision of neatly distinct alternative paths. The lost words here had the potential to alter history, depending on the mercurial effect of their delivery. Martin Luther King Jr.’s celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech diverged significantly from the prepared text. The text remains “undelivered,” but King delivered the speech he wanted to deliver. To what extent can we take the forsaken texts here as an indication of what the speakers would actually have said had events permitted? Can we know the counterfactual, given the way that speeches interact with listeners and spread through media?

What we think we want to say is ultimately highly contingent: a function of history. The book includes marked-up speech texts that show the entanglement of the processes of writing and thinking, how editing clarifies our thoughts and negotiation with gatekeepers (whether editors or conference organizers) shapes what gets said. As anyone who has written anything knows, it is through drafting that we arrive at what we really want to say. First drafts are often cathartic, as Nussbaum notes. They are the soul-unburdening that allow you to form the words that you do want to say, aware that speech (unlike a diary confession) is a social act. There’s a fine but important distinction between undelivered speeches and speeches never intended to be delivered.

Take the speech that Boston’s progressive Mayor Kevin White drafted in 1974, when court-mandated busing designed to integrate the city’s schools met with violent pushback. The speech proposed steps to halt the busing. But was it ever meant to be given? Or did White write it more to understand and test the arguments in favor of that position—or as a possible strategic bluff to elicit badly needed support from other offices? His proclamation in the speech that he did give, that “there is no odor, save death, worse than that of a public official too frightened … to say … what he honestly believes,” intimates a core value of integrity—not just “smart politics”—that would have made it highly unlikely he could have delivered the other speech.

A similar process is evident in the speeches that John F. Kennedy’s staff drafted for and against an airstrike during the Cuban missile crisis. Kennedy’s appointment of his pacifist speechwriter, Ted Sorenson, to the decision-making committee suggests an awareness of the role of writing in such processes—and Sorenson’s efforts to clarify the anti-strike position while drafting speeches for both sides (according to Nussbaum’s stunning detective work) proved pivotal to the outcome. Though both drafts offered nearly identical promises to retaliate against nuclear attack, the pro-airstrike version also included language “likely to have come from someone morally opposed to nuclear weapons,” Nussbaum discerns. “Nuclear weapons are so destructive,” the speech reads, “that a sudden shift in the nature of their threat can be deeply dangerous.”

Professional speechwriters face the recurring challenge of writing persuasively for positions with which they disagree. This is simply part of the job, explains Nussbaum. But he also recognizes that “to hold the pen is to hold the power,” and his stories offer repeated testimony of the outsize influence of idealistic speechwriters. If speechwriting requires “becoming a Method actor” to “channel your boss” when you don’t know what exactly is in their head, the bosses here often only seem to understand what’s in their own heads through the suggestive power of speechwriting. Nixon’s toggling between the decision to resign or not to resign shows in real time how the working out of arguments on paper clarified his grasp of his real options. The undelivered speech refusing resignation in favor of seeing the constitutional process of impeachment through acknowledged the evidence against him but invoked the risk of “instability” and “descent toward chaos if Presidents could be removed short of impeachment and trial.” It was the best argument his speechwriter Ray Price could make, and even Nixon was not convinced. He went with Option B, which affirmed the importance of putting “the interest of the nation … before any personal considerations.”

Opening up a box of tantalizing what-ifs, Nussbaum consistently finds that the path history took was the best possible one. Lewis’s and King’s speeches, for instance, turn out perfectly balanced for “the needs of the moment”—though we can’t know what (perhaps more powerful?) impact a different balance might have produced. Humbly disclaiming historical authority, Nussbaum accepts the liberal understanding of history as an exalted (if not otherworldly) force of its own: “History—with a capital H.” In this providential outlook, all events, even seemingly evil ones, ultimately forward a story of progress, and the great must at times rise above ordinary mortality with the promise of vindication by history. It’s an assumption of an “arc of history” (President Obama’s pet phrase), itself propagated across time on the wings of momentous speeches, inspiring moral courage but also moral recklessness, as I’ve described in my recent book Time’s Monster.

The very idea of the speaker as the fount of political action, inspiring ordinary people to act, stems from this liberal historical imagination. Nussbaum’s “instinct about where to uncover a never-given speech,” depends on a narrow definition of what counts as a speech: These are famously undelivered speeches. The array of “occasions” for such speeches are events pre-invested with historical meaning (inauguration, commemoration, annual awards ceremony)—hence the presence of technological amplification (mass media like newspapers, radio, television) allowing the audience and a vaster remote audience to be addressed at once.

But

these are merely the speeches we know went undelivered; what about the unknown

undelivered speeches—all those “occasions” when we craft words, on paper or in

our minds, but shrink from giving them utterance? Which of these numberless conceived

but undelivered “speeches” count as likely to have changed history (even if our

inability to voice them in that moment is itself a function of history)?

Certainly, in a world in which a historical imagination centered on great men and hinge moments of history deeply influences our understanding of our agency, the words of the great have outsize impact. But as one great man, Mahatma Gandhi, noted, the sustaining force of love—conveyed through everyday speech by ordinary people—routinely defuses would-be conflicts in a manner illegible to liberal conceptions of history. History is, in fact, the unceasing flux of life, a continual quarrel between ethics and circumstances that shapes the ends of each of our lives. Ordinary people routinely make history without inspiration from a podium, evident in Undelivered’s depictions of the crowds who time and again determine who can speak and what they can say. Speeches that matter include the exchanges integral to group activism, such as the addresses that daily fueled protest from 2020 through 2021 by Indian farmers—speech that merges with song, slogan, and poetry, that is entwined with action. The danger lies not only in listeners at speeches failing to recognize their agency, as Nussbaum warns, but in imagining their agency as purely reactive.

Coming at a time of mass protest and a global authoritarian turn, Undelivered longs for enlightened leadership. Some speeches by great leaders of the past (such as FDR’s dying call for peace) are included less for what they might have done than out of a hope for what they might do now. But the book’s own account of how speechwriters have come to craft lines for politicians pretending intimacy with their audiences illuminates some of the sources of diminishing faith in such figures: a culture in which politicians don’t mean what they say and citizens assume that their speeches are mere rhetoric—at worst, lofty words lending cover to violent action. Whatever its valorization of guidance from the top, the stories here invite reflection on the power of ordinary people to make history, even from delayed utterances conveyed on paper rather than from a podium.