CIA scientist Jon Monett was known around agency headquarters as a technical genius akin to James Bond’s gadget inventor, Q. Following his 1990 retirement, Monett dabbled in private intelligence. Then, in 2008, he formed a nonprofit called Quality of Life+, which seeks to bring together engineering students and needy veterans to create life-enhancing prosthetics.

The tax-exempt organization was first housed at Monett’s alma mater, California Polytechnic State University, and forged partnerships with 19 other universities nationwide. QL+’s success was threatened in December 2020, when the Los Angeles Times revealed that it was beset by a toxic work environment driven by Monett, who was accused of sexually assaulting at least two women, one QL+ employee and one woman from Cal-Poly. Monett’s lawyer described the allegations as “99 percent” false and defended his client as an indispensable spymaster turned veterans’ advocate. In the wake of these allegations, Cal-Poly severed ties with QL+, Monett resigned, and an interim executive director claimed that the charity’s benevolent mission would continue unfazed.

But behind the scenes—according to sources who have worked for QL+, company documents, and affidavits related to ongoing litigation—QL+ continued to grapple with myriad other issues, including allegations of inappropriate financial and accounting practices, conflicts of interest, retaliation against whistleblowing employees, and questionable expenses. (The nonprofit didn’t respond to written questions and interview requests.)

Former officials said they also struggled to corroborate many of the organization’s lofty claims. “There was no comprehensive database or real effort to try to measure the organization’s impact,” Charles Kolb, QL+’s former executive director, told me. “The numbers were not adding up,” explained another former official. While Monett’s credentials gave the impression that QL+ held standards befitting MI6, a source who worked through Cal-Poly told me that prosthetics and other assistive devices were often unusable or quick to break, an observation backed up by others. “Veterans are expecting this equipment to solve a problem, to improve their quality of life,” this source said. “In reality, these are high-end, science fair–level prototypes. A lot of them didn’t work.”

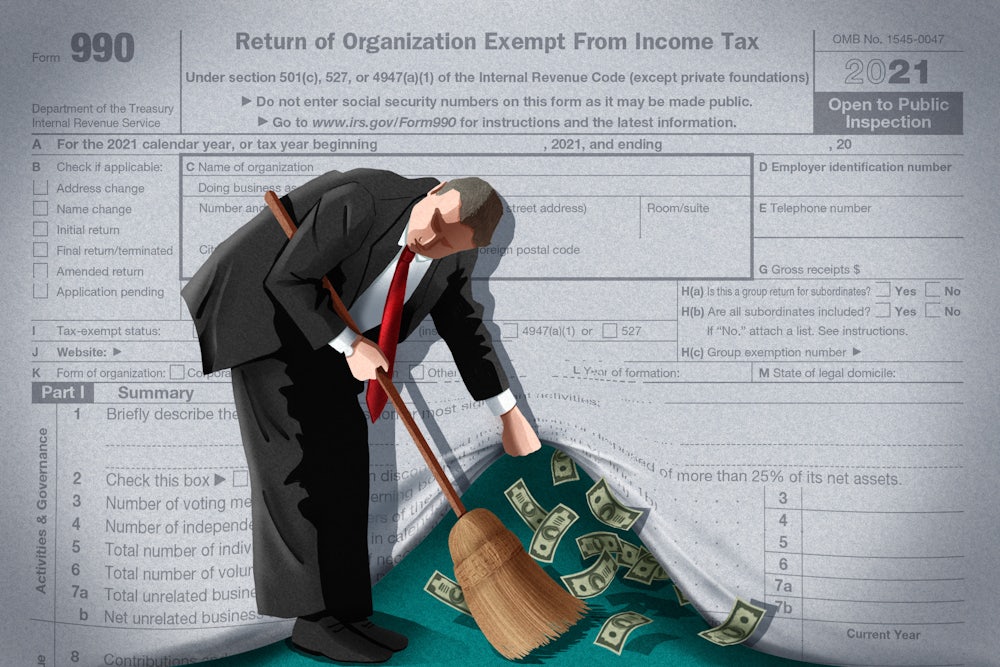

While the Times reported heinous sexual abuse, QL+’s opacity and questionable impacts reflect endemic issues in the nonprofit industry. Last year, a QL+ official alerted a colleague over email of their belief that the nonprofit was “manipulating” their accomplishments in Internal Revenue Service forms through a counting scheme that inflated the number of volunteers. A second, more senior official agreed that the behavior should stop but shut down efforts to revise public impact statements. “They wanted to brush everything under the rug,” vented a former official. “I left because I couldn’t have my name attached to these lies.”

As an investigative reporter on the veterans’ beat, it can sometimes feel that former service members attract do-gooders and bad actors in equal measure. Some of the most infamous nonprofit scandals have been exposed inside veterans’ organizations. But misbehavior extends to organizations of all stripes. In the last year alone, journalists and government investigators have reported bribery and sexual abuse in a major homeless shelter network, embezzlement from the leader of a Latino support center, and fraud in a group organizing food assistance. (These are but a few examples.)

Effective oversight is vital for the nonprofit world to thrive. It can discourage misconduct, make cheated parties whole, and ensure a group’s mission is met. When the system works correctly, bad actors are brought to justice. But as the number of nonprofits has exploded to just shy of two million organizations, the industry remains plagued by chronic underregulation.

This lax environment was formed through a perfect storm of misguided court rulings, political attacks against the IRS, deceptive charity ratings, and a persistent and uniquely American belief in the power of private-sector altruism. And it’s about to get a lot worse, thanks to a 2019 law pushed by former President Donald Trump that’s forcing the IRS to essentially dismantle the part of the agency dedicated to uncovering tax-exempt schemers. Such contempt for this oversight stems from the Republican-backed, Obama-era investigations into the service for rightly scrutinizing Tea Party groups that were pushing legal boundaries.

Rob Reich, a Stanford professor and author of Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better, argues that America’s “atypically permissive approach” to regulating philanthropic ventures secures financial and reputational benefits to donors and executives. This environment can also cheat the vulnerable populations whom nonprofits claim to help. Summing up the state of regulation, Reich was blunt. “You really have to blow it to lose your nonprofit status,” he said.

During his famed 1831 trip to the United States, Alexis de Tocqueville marveled at the population’s strong social fabric—conditions, he theorized, that were accomplished through the formation of “associations to give fêtes, to found seminaries, to build inns, to raise churches, to distribute books, to send missionaries to the antipodes.” Two years before his visit, a far less famous Boston intellectual named William Channing offered a warning about this growing constellation of groups, which he deemed an “irregular government” that needed to be “watched closely.”

When it came time to draft legislation on how to tax these organizations, lawmakers hewed to de Tocqueville’s ideas, incentivizing the creation of associations by exempting them from governmental duties.

Charitable organizations offer the ability to give beyond government, but also provide the powerful with a valuable tax shelter, a tool for image-making, and an avenue for gaining soft power. This was understood by the robber baron and charitable powerhouse Andrew Carnegie, who, in his essay “The Gospel of Wealth,” concluded that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” Unstated was Carnegie’s vehement opposition to income and property taxes, money that can be democratically directed to public institutions capable of accomplishing great things.

Federal government services are today overseen by a raft of watchdogs, including House and Senate committees, the Offices of Inspector General, and the Government Accountability Office. There are correspondingly few structures in place to dig into nonprofit behavior. Perhaps the most promising effort to increase accountability came in 1969, when Congress imposed a small excise tax on private foundations with all funds meant to support the IRS’s Exempt Organizations (EO) office. Unfortunately, the influx of money didn’t actually make it to this office, leaving it perpetually underfunded.

Despite budgetary challenges, the IRS has shown itself to be a capable regulator. In the 1970s, agents righteously investigated private tax-exempt Southern schools that had imposed de facto segregation. Many other shady actors were caught through audits and random application reviews. Through this work emerged institutional knowledge and legal theories that helped clarify vague statutes.

When Marcus Owens ran the EO division from 1990 to 2000, he had a fleet of about 120 lawyers and certified accountants. In addition to their core oversight work, employees fanned out to field offices to train other IRS officials on the ins and outs of nonprofit regulation. They also released continuing education materials every year that featured evolving guidance.

These efforts were kneecapped through the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998, a bipartisan law that reined in the department’s powers. It passed following a series of overheated congressional hearings in which members of the public essentially complained about the IRS enforcing the law. Nevertheless, President Bill Clinton expressed outrage and promised change. His resulting package increased the burden of proof needed to punish rule-breakers and weakened agency operations. As part of this work, EO lawyers with nonprofit expertise were shuffled elsewhere. The IRS’s overall staffing levels decreased significantly over the next few years. Beginning in 2005, the EO training materials were no longer updated.

In 2012, Republican lawmakers accused the EO office of being a corrupt body of lefty rogues targeting Tea Party groups in its “Be on the Lookout” list. In truth, these were triage tools meant to ensure that the flood of politically influenced nonprofits that emerged in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United maintained rules against participating in political campaigns. The office was flagging groups all over the spectrum, and its enhanced reviews rarely led to denials.

Still, the IRS is an easy enemy, and once again became Congress’s cat toy. This led to a purge of leaders, a host of morale issues, and less regulation. Among other things, the IRS sought to shrink its massive backlog of applications by creating an “EZ” form for small groups that required no supporting documentation. Lawmakers further restricted the EO mission by prohibiting officials from spending federal funds to regulate potentially improper political activity. By the time the multipronged, multiyear inquiry was exhausted in 2016, the EO’s $102 million budget had been slashed by $20 million, and the office had lost hundreds of employees.

A few years later, in 2019, the IRS’s watchdog evaluated a representative sample of organizations using the EZ form and found that nearly 50 percent did not qualify for their tax-exempt status. The report noted that even when organizations correctly followed incorporation guidelines, many had a mission and scope of activities that clearly didn’t qualify for tax-exempt status.

This paltry oversight will soon get worse, thanks to the Trump-era Taxpayer First Act, which, among other things, makes it harder for nonprofits that haven’t filed the proper paperwork to lose their status. Documents laying out a broad reorganization launched by the law further show that the EO office is set to be scrapped, with responsibilities divvied up to other parts of the agency. “For all intents and purposes, the IRS is getting out of the tax-exempt services business,” Owens observed.

As the IRS retreats, what remains is a series of piecemeal and imperfect oversight efforts. Attorneys general in states such as New York, California, and Massachusetts have stepped in to police nonprofits. Harvey Dale, who directs NYU’s National Center on Philanthropy and the Law, said these offices do good work, but have “many other fish to fry.” More to the point, many states have no full-time employees focused on the sector.

One government lawyer vented that even if her state exposes scammers, many simply move and reregister in friendlier states. “It’s a game of whack-a-mole,” she said. “And bad actors will simply relocate where there is very little or no regulation.” Florida may be the most welcoming, with nonprofit regulation relegated to an office focused largely on agriculture. Asked why more states don’t focus on nonprofit misbehavior, Dale said, “Some wags say AG doesn’t stand for ‘attorney general’; it stands for ‘aspiring governor.’ And there’s no real political payoff for overseeing charities.”

There’s also a slew of private charity raters, such as BBB Wise Giving Alliance, Charity Navigator, and GuideStar. These groups confer a sheen of credibility on nonprofits through numerical ratings and gold stars. And yet a large number of problematic nonprofits enjoy high ratings on these sites.

While Charity Navigator initially placed an advisory on QL+, noting the allegations in the Los Angeles Times, it removed any mention of the scandal, following communication between the two parties and what a Charity Navigator official described as proof of “corrective action.” In internal emails, the QL+ leader also expressed a need to focus on GuideStar, “so we can reference that rating in our grant applications and marketing.” Currently, QL+ has a “platinum” rating from GuideStar, which, a few years ago, merged with a nonprofit focused on supporting the charitable sector through fundraising information and other assistance, presenting potential conflicts of interest. Officials from these organizations broadly defended their practices, though a GuideStar official vented over the lack of available public information on nonprofits and compared 990 data—the forms nonprofits are required to submit to the IRS on a yearly basis—to “Swiss cheese.”

These ratings are routinely called out by CharityWatch, the only real aggressive watchdog. The organization helps journalists interpret IRS nonprofit disclosures while revealing how the documents themselves can be easily gamed to understate executive compensation and overstate impact. “The whole system is propped up on false assumptions and flawed automated methods,” said Laurie Styron, CharityWatch’s leader.

CharityWatch has also supported efforts to impose new accountability, transparency, and spending measures over nonprofits, laws that have faced political headwinds, gubernatorial vetoes, and legal skepticism. Last year, for instance, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a California law mandating greater donor disclosures inside nonprofits, calling it a violation of the First Amendment. This followed similar Supreme Court rulings that, among other things, shot down a state law requiring charities to spend a minimum percentage of their annual budgets on program activities and to limit overhead.

This laissez-faire approach has spiked alongside Covid-19, a national crisis that, like others before it, has led to a proliferation of bogus charities. The IRS itself warned of this ongoing crisis in early June and offered consumer tips on how to avoid being scammed. Meanwhile, the EO office withers, and actual oversight is at historic lows, with the IRS last year revoking the nonprofit status of fewer than 100 organizations.