On a daily basis now, Brad Woodhouse, a longtime Democratic strategist who co-chairs the Defend Democracy Project, a nonprofit group focused on fighting efforts to undermine democratic elections, gets on the phone with a number of allied outside groups and committees to advise them on messaging, voter outreach, and what to be prepared for on Election Day—and, perhaps especially, right after.

According to Woodhouse, he urges the people on these calls to “use election denial from candidates and shenanigans by them and their allies to remind people what’s at stake and why it’s so important for them to vote and not let the suppressors win.”

The conference calls are one example of the steps Democrats are taking to counter what they expect will be an unprecedented wave of misinformation and last-minute voting hijinks by conservatives to change unfavorable results.

Examples of GOP trickery are easy to find. In Georgia, a flyer was distributed in some Democratic-leaning Atlanta suburbs saying early voting ended on October 30 (it actually went until November 4). In Illinois, the state Board of Elections warned voters about a text message going out to voters sending them to the wrong polling places. In Oregon, a political flyer has been circulating that claimed to offer directions on “How to Protect your Vote” but peddled false information on the proper way to vote: that voters have to use blue, not black, ink, or that they need to make their ballots with a big check mark. In Clark County, Washington, the Republican nominee for county auditor, Brett Simpson, falsely claimed that election fraud was rampant throughout the county.

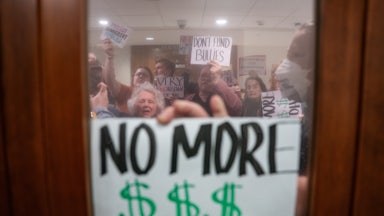

In the final days before the election, Democratic outside groups have been setting up ways to fight all of this—through organizing lawyers, dispatching voter protection teams across the country, and activating hotlines to help Americans vote. But the question is: Are they truly ready for what many think will be an unprecedented tornado of challenges and misinformation?

“The groups with lawyers are lined up. The grassroots are lined up, and they’re all getting ready to react,” said Adam Bozzi, the executive vice president for communications for End Citizens United/Let America Vote, a political action committee that focuses on protecting voting rights. “Everybody is well aware what happened in 2020. Everybody has seen the last two years, where there has been a concerted, coordinated effort on the other side to both restrict access to voting and put in place the pieces to sabotage and overturn future elections. There have been alerts and alarms going off for a long time now, and so our side is going to be ready.”

In addition, federal law enforcement agencies are on alert going into Election Day over the threat environment that could result from perceptions of voter fraud, legal challenges, and extended election certification processes. The FBI is coordinating with departments from the Department of Homeland Security and the National Security Agency to respond to potential Election Day threats.

The Democratic National Committee has gone a step further than in past cycles. For the first time, it has hired a set of anti-subversion “voter protection directors” in a few states where, according to a DNC official, “their job is specifically focused on Republican efforts to subvert the vote” by methods such as trying to delay election certification. The committee has assembled 25 voter protection directors as part of a staff of more than 100 on the ground around the country. Staff have been deployed to five priority states: Arizona, Nevada, North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Texas—which has a number of high-profile congressional races. Staffers there are charged with helping to make sure all ballots are counted “and that election results are certified.”

The committee is also preparing for litigation and has already been involved in a number of election-related lawsuits. In Arizona, the DNC won a lawsuit Republicans brought that challenged whether no-excuse voting by mail is constitutional. In Pennsylvania, the DNC was able to block a GOP lawsuit that aimed to stop counties from giving voters a chance to fix mistakes on their mail-in ballots. And in Wisconsin, the DNC intervened in a lawsuit in order to make sure eligible voters who had their absentee ballots rejected had opportunities to fix their ballots on Election Day or before.

Similarly, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the campaign arm for House Democrats, has its own voter protection program. The DCCC has a national and deputy national voter protection director overseeing six regional directors who “work every day to ensure everyone who is eligible to vote can vote and have that vote counted,” according to a DCCC official. The committee has also trained hundreds of observers to make sure they have poll watchers at voting locations across the country. The DCCC also has a voter protection team that aims to help voters across the country correct their rejected ballots so that their votes can be counted. The widely respected Marc Elias, the Democratic elections lawyer, is the DCCC’s general counsel this cycle—a sign that the committee has long seen election challenges as a high possibility this cycle.

State Voices, a nonpartisan network of organizers and advocates that aims to fight for a “multiracial democracy,” helps lead the Election Protection Coalition, a set of organizations focused on protecting voting rights. It’s the largest national nonpartisan voter protection group. Its affiliate and partner organizations have specific plans for deescalating tense situations at polling sites and helping to train poll monitors. For instance, in Georgia, affiliate groups are involved in election board monitoring, supporting and promoting voter hotlines, and recruiting poll monitors.

Bozzi, the End Citizens United/Let America Vote top communications staffer, said most of what his group would be doing in the final days leading up to the election would be in traditional media and social media, fighting misinformation and raising awareness about voting. “We’re going to probably [be] helping mobilize grassroots when that needs to happen,” Bozzi said. “We have been and are going to counter misinformation and disinformation through social media, earned media opportunities, and general coalition work.”

There’s an air of secrecy to the work some of these groups are doing. One Georgia Democratic operative pinged for this story responded by saying, “Not sure how much we can say on the record as we don’t want [Republicans] to get hip” to Democrats’ precautions. Other Democrats reached for this story declined to comment, saying only that their groups and allied organizations are in regular contact.

It all sounds impressive. But for all the effort going into urging supporters to vote, early indicators offer a mixed picture on that front. For example, in Detroit, a huge Democratic stronghold in a very important state, where Democratic incumbents’ governorship and other statewide offices are up for grabs, the city clerk recently predicted that turnout would be somewhere between 28 percent and 33 percent lower than in the most recent midterm. More disturbing is that early vote totals across the country indicate strong Republican enthusiasm, according to an analysis by the Times, especially in states where Democrats had hoped to be more competitive. In Florida, for example, according to the United States Election Project, 23 percent of Republicans have already voted while just 21 percent of Democrats had. That’s particularly shocking, as the Times notes, because Democrats in that state oftentimes go in with an early voting lead. At the same time, there are promising signs for Democrats. Already the number of early votes cast have surpassed the early vote total in 2018—suggesting Democratic enthusiasm might not be at record lows.

The real test for these Democratic groups may come after voting—when many conservative candidates make good on their promises to refuse to acknowledge the election results if they don’t win. At that point, all of the preparations these groups will have made will once again be put to the test. It’s becoming a normal part of American elections: Votes are counted, and then some hard-line candidates baselessly claim election fraud. That’s when efforts to protect the integrity of elections are really put to the test.