I understand that most folks don’t live and breathe the gory details of health care policy. It’s mind-numbingly complex and frankly kind of boring. But when it goes wrong, bad things happen. Really bad things.

A global pandemic is an example of one of those things. There are, of course, many narratives about how this pandemic came to pass. Here’s one: A new virus emerged with the unique characteristics to spread quickly and sicken and kill enough people that it would take millions of lives—but not enough that hucksters couldn’t possibly deny its seriousness (This wasn’t Ebola, with a nearly 50 percent mortality rate, after all.) There’s also this one: Any semblance of unity in the face of a shared challenge was sacrificed at the altar of America’s political polarization—foreclosing the kind of collective action that could save lives through universal masking or vaccination. Or a third: America’s public health infrastructure had been hollowed into a shell of itself through the austerity years of the Great Recession, leaving us uniquely vulnerable to this inevitable threat. Oh, and we can’t forget this one: Millions of people lost their health insurance in the pandemic. Millions more have been left in profound debt because of how bad so much health insurance is. Millions remain at risk.

All of these things are true. And every single one of them should point us toward seeking political solutions to America’s profound health crisis. That’s what our before-times selves had determined, at least, even before we lived through a global pandemic. Health care was among the top issues voters claimed they cared about as they headed to the polls in 2018 and 2020. And the parties responded. Much of the 2020 Democratic primary was duked out over health care policy—Medicare for All versus all of its variously bastardized cheap replicas. Republicans kept arguing that we should “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act (with what exactly? We’ll never know because they never passed anything—the public policy equivalent of how many licks it takes to get the center of a Tootsie Pop). But apparently we don’t care about health care anymore? Or at least that’s not what parties want to talk about in 2022. Which is a curious thing because … well, the pandemic.

So why didn’t either party talk about health care in 2022? Why didn’t voters demand that they do? There’s the most obvious reason: that what started out as a health crisis has transmogrified into an economic one. In the face of inflation, spiraling rents, absurdly high mortgage rates, and an economy that is actively being driven into recession by the Fed, health care simply isn’t the issue on the top of most Americans’ minds. But health care remains one of the most pressing sources of financial insecurity for most Americans. Health care debt is the single biggest cause of personal bankruptcy, after all. And there’s no evidence that the problem has gotten any better during the pandemic.

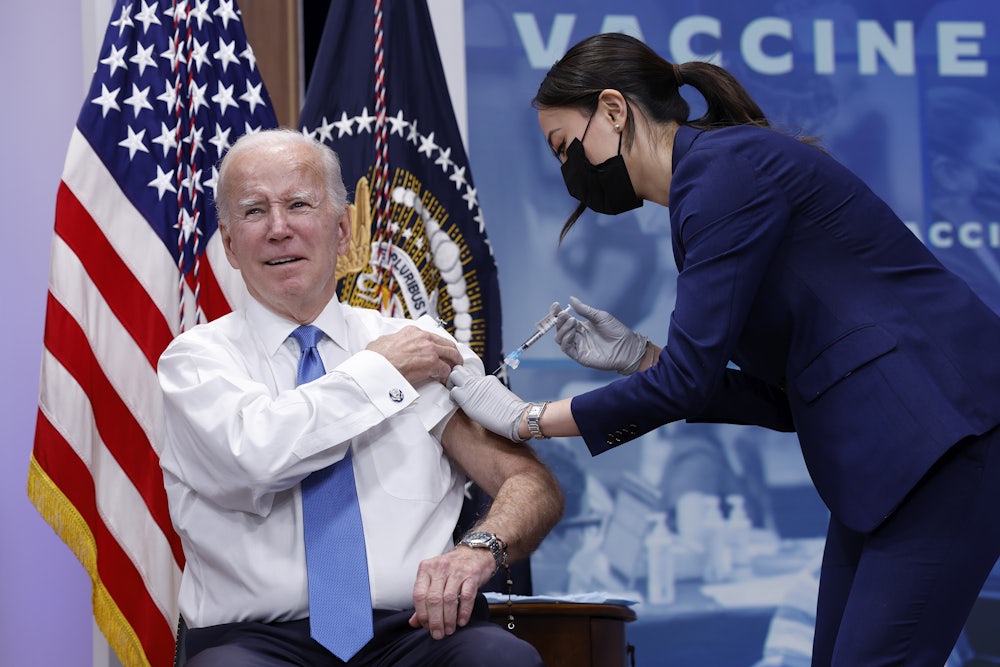

For their part, Democrats are reluctant to continue to talk about health care for a few reasons. First, a conversation about health care will inevitably lead to one about the pandemic. And it’s clear that President Biden would rather not talk about the pandemic—because it’s “over,” as he told 60 Minutes. Conversations about the pandemic inevitably lead to a rehashing of early pandemic school closures or later pandemic vaccine requirements that Democrats don’t want to defend (although these were lifesaving policies). Besides, Democrats would rather point to what they’ve accomplished. The Inflation Reduction Act will extend ACA subsidies for millions of people for several years. For the first time, it also empowers Medicare to negotiate certain prescription drug prices on behalf of beneficiaries and restricts arbitrary annual price hikes. These are, in the words of the president, a Big F’ing deal. And yet they’re far short of what Democrats ran on in 2020. Indeed, the party platform called for a public option and substantial investments in long-term care for seniors and people with disabilities.

Republicans, for their part, seem no longer to want to repeal and replace Obamacare. It seems the culture war no longer sees the rush to destroy the first Black president’s signature health care law as sufficient grist. It’s moved on to juicier subjects: grooming rings, indoctrination, and replacement theory. Besides, the “serious” Republicans never had a plan for the “replace” part, anyway.

So, two and a half years into the pandemic, that leaves us in a paradox. No single issue has so fundamentally altered American life as has the pandemic—an issue that is squarely about America’s approach to public health and health care. And despite a vigorous public debate about how to address America’s clearly failing public health and health care systems going into the pandemic, the conversation about how to fix them has all been snuffed out as we emerge from it … even though we have done next to nothing about them. The health care industry is breathing a sigh of relief after vigorously fighting any effort for reform in the last two elections.

A recent New York Times/Siena poll found that 70 percent of would-be voters believed that democracy was in crisis. Only 17 percent of them believed that the crisis was a matter of the creeping rise of authoritarianism. Instead, most believed that the crisis of our democracy was corruption—the obstacles of money and influence that prevent it from translating the public will into public policy. Perhaps our failure to solve America’s health care crisis—despite a pandemic—is a perfect example.