It hasn’t received the same attention as recent abortion or gun rights rulings. But in the past decade, the federal judiciary, with the Supreme Court leading the way, has become increasingly hostile to business regulations and eager to reshape the law in favor of corporate interests. That trend is being tested this term in a battle over Proposition 12, a ballot measure approved by California voters banning the sale of pork that was produced by keeping pigs confined in tiny cages.

Although the justices seem poised to reject the most extreme arguments that business interests have made against Prop 12, a less sweeping ruling in industry’s favor still appears to be on the table. While that result might initially look moderate—and may ultimately allow Prop 12 to survive—it would be deeply problematic for environmental, health, and safety laws in the years ahead.

The lawsuit challenging Prop 12, brought by pork producers, relies on new constitutional theories that depart from settled precedent. (Disclosure: I helped file an amicus brief on behalf of law professors in support of Prop 12 at the Supreme Court.) But despite the willingness of many current Supreme Court justices to abandon precedent when it clashes with their ideology, there’s reason to think that the justices view the pork producers’ claims as going too far. Based on the questions at oral arguments this October in National Pork Producers Council v. Ross, the court might very well reject the pork producers’ lawsuit entirely. Or it might limit the scope of the lawsuit and return it to the lower courts, where Prop 12 will likely be upheld in the end.

Some court watchers have described the second option—letting the case proceed on a more limited basis—as a narrow ruling that would allow the justices to avoid confronting some tricky questions in the case. But even though this would likely leave Prop 12 intact, it would be far from a neutral compromise. Even a “narrow” ruling allowing the case to proceed would make it easier for industry to challenge health and safety measures in court. And ostensibly “moderate” rulings like this are among the ways that today’s Supreme Court moves the law further and further toward privileging the interests of big business.

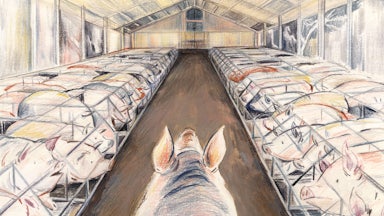

When California voters approved Prop 12, they had two goals: reducing the risk of foodborne illness caused by tightly packing farm animals in densely crammed facilities and enabling Californians to buy pork without subsidizing animal cruelty. Pork producers lobbied hard against Prop 12 in the media, but Californians overwhelmingly approved it. The industry then tried to persuade Congress to override the law, but those efforts failed too.

Having lost twice over in the political process, industry groups went to the courts, arguing that Prop 12 violates the “dormant Commerce Clause,” a long-standing but controversial doctrine limiting state authority to regulate in ways that affect interstate commerce. Prop 12 operates only within California, but the pork producers’ lawsuit rests on the premise that it will have costly ripple effects in other states because the industry is highly integrated nationwide.

This premise is dubious. Pork companies like Perdue, which filed a brief supporting Prop 12, already avoid the use of tiny crates, while other companies like Smithfield and Tyson have said they can make the necessary changes without difficulty. In the words of Hormel Foods, there is “no risk of material losses from compliance with Proposition 12.” And agricultural economists have debunked the notion that Prop 12 will raise the price of pork outside of California.

But even assuming Prop 12 could cause nationwide industry ripple effects, there still would be no constitutional violation—at least under existing Commerce Clause precedent. Indeed, that was the view of a federal appellate panel—composed primarily of judges appointed by Republican presidents—that first reviewed this case. As they explained, California is not impermissibly regulating in other states just because its law might have incidental effects on pork production there. And the possibility that some companies might have to adjust their production systems to keep selling in California doesn’t qualify as an interference with interstate commerce, because businesses have no constitutional entitlement to their preferred operating methods.

Arguing their case before the Supreme Court in October, the pork producers seemed to make no headway on their most radical argument—that a state like California impermissibly regulates beyond its borders whenever its laws have ripple effects outside the state. That logic would devastate states’ legislative power, and thankfully the court seems poised to reject it.

But justices of varying ideological stripes did raise questions about one of Prop 12’s two goals: allowing Californians to avoid complicity in farm production methods they find immoral, even when the production happens outside California. These questions focused less on Prop 12 itself than on concerns about how far states could push this type of rationale in other hypothetical laws.

Many court observers have speculated that at least some justices may look for a way to avoid saying anything now about when states can or can’t ban goods based on moral objections to how they were produced. One possibility, they say, is that the justices will send the case back to the lower courts to hear evidence and engage in a balancing test—weighing the value of Prop 12 to Californians against any detrimental effects it has on interstate commerce.

The justices don’t have to do this. They could instead focus on the other of California’s two reasons for enacting Prop 12: to reduce disease transmission within California by eliminating meat that comes from overcrowded farm facilities. As the state’s voter information guide explained, scientific studies “repeatedly find that packing animals in tiny, filthy cages increases the risk of food poisoning.” This separate rationale provides an independent basis for the law, apart from moral objections to subsidizing animal cruelty. And states have always been able to protect their residents’ health and safety by prohibiting dangerous goods. The justices could simply affirm that long-standing precedent to reject the pork producers’ lawsuit.

If the justices do revive the case by sending it back to a lower court for an evaluation of whether Prop 12’s costs outweigh its benefits, this could have far-reaching repercussions. The law itself should still be safe, because the pork producers’ exaggerations about Prop 12’s effects are so obvious, and the value of Prop 12 is similarly clear.

But reviving the case in this way would also expand industry’s ability to challenge state laws in court. That’s because reviving the case would require the Supreme Court to backtrack, implicitly or explicitly, from important precedent that limits the reach of the dormant Commerce Clause.

In rejecting the lawsuit, the court of appeals concluded that the pork producers’ predictions about Prop 12 (dramatic as they are) simply don’t allege the kind of burden on interstate commerce that can ever outweigh the value of a state law. All that the pork producers are claiming, the court noted, is that they will have to spend money complying with Prop 12 if they want to keep selling in California. But as the court explained, “Laws that increase compliance costs, without more, do not constitute a significant burden on interstate commerce.” It’s not enough, in other words, to allege that companies will have to give up a more profitable method of operating, because the Constitution doesn’t protect any company’s preferred business model.

Supreme Court precedent makes this point clear. In a 1978 case involving Exxon, for instance, the court rejected the notion “that the Commerce Clause protects the particular structure or methods of operation in a retail market,” as well as the notion that interstate commerce is burdened “simply because an otherwise valid regulation causes some business to shift from one interstate supplier to another.”

Any decision by the Supreme Court that retreats from this principle—by sending the case back to a lower court to conduct a cost-benefit analysis, for instance—would amount to a declaration that the Constitution does to some extent shield companies’ preferred business practices from state interference. Justice Gorsuch pressed this point during the argument, observing that Prop 12’s challengers are really just alleging harm to “large pork producers” who aren’t currently set up to comply with Prop 12, which is not the same as “harm to competition or harm to interstate commerce itself.”

If the court were to endorse the idea that companies can sue whenever obeying a state law would make their preferred operating methods more expensive, the result would be much more litigation in which judges are called upon to second-guess the wisdom of choices made by voters and legislatures.

And that’s not all. Until now, the very concept of having judges “balance” a law’s benefits against its costs to determine whether there’s a constitutional violation has been a matter of fiction more than reality. Yes, Supreme Court opinions routinely say that this type of balancing is one way that a state law can be deemed invalid. But that has never really been borne out in practice. Instead, for nearly a century, the court has struck down only two types of laws under the dormant Commerce Clause: protectionist barriers that discriminate against other states’ products and restrictions on transporting goods through a state’s territory.

Prop 12 doesn’t fall into either category. So a decision reviving the pork producers’ lawsuit will inevitably be taken to mean that a wider range of state laws are vulnerable to constitutional challenge. What might seem to be a narrow ruling, in sum, would not be narrow at all.

To be sure, industry wouldn’t get everything it wants if things turn out this way. After all, the pork producers’ most far-reaching arguments will have failed. But that is how corporate interests often make advances in today’s business-friendly Supreme Court. Aggressive new interpretations of constitutional and statutory provisions are routinely foisted on the justices, supported by a coordinated array of amicus briefs from industry and allied groups. Sometimes these broad arguments are accepted, resulting in watershed decisions transforming American law. Other times, corporate interests secure only a partial victory, reshaping the status quo more incrementally. On occasion, these efforts simply fall flat. Regardless, under this court, the law moves in only one direction: looser constraints on business, despite the choices made by Congress, voters, and the states.

The relentless barrage of new arguments against government regulation, and the judiciary’s increasing receptivity to them, can tend to make industry’s partial victories seem modest, even a compromise. That may be how some would view a decision to revive the pork producers’ lawsuit in the limited way observers have predicted. But even though Prop 12 would almost certainly survive such a ruling—and that’s important—there should be no illusion about what such a decision would represent: yet another advance of corporate interests at the expense of the democratic process.