Jimmy Carter’s tireless efforts to bring Israel and Egypt together in a peace agreement during the 1978 negotiations at Camp David can be seen today as the most consequential contribution any U.S. president has made toward Israel’s security since its founding. The treaty earned the Israelis literally 100 percent of what they had so long sought: a separate peace treaty that ended not only the state of war with their most threatening neighbor, but also the freedom to carry out their other strategic and military objectives without concern for igniting a regional war. (It also defenestrated the boycott of Israeli and Jewish products, people, and culture across the Arab world.)

However “cold” the peace may have been in terms of the actual relations between the two peoples, it has withstood countless Israeli actions that might have dislodged it: Israel’s occupation of an Arab capital (Beirut); its air attacks on numerous Arab countries; its demolition of nuclear reactors in both Iraq and Syria; subsequent mini wars in Gaza against the ruling party there, the Islamic fundamentalist Hamas, and in Lebanon against Iran’s guerrilla allies, Hezbollah; the occasional bombing of military targets in Syria; and the violent crushing of two Palestinian rebellions on the West Bank (the first and second Intifadas), together with its apparently endless occupation of and settlement expansion in what was supposed to be Palestine. It needs to be mentioned that in many of these instances, Israel was responding to various attacks, kidnappings, bombings, Scud missile firings, and other violent incidents according to its own doctrine of “asymmetric deterrence.”

So Carter did a great and historic thing. But what he never understood was that he wanted this peace for Israel far more than American Jewish leaders did, and even more than many Israelis. He took political risks for it that no Democratic president before or after him has been willing even to imagine. He paid for his success with a consistent campaign of vilification by these same Jewish leaders, and most of them never forgave him for the tenacity with which he pursued his vision of Middle East peace.

Both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama wanted to pursue Arab–Israeli peace, but neither proved willing to risk the political capital necessary to come close to success (Clinton tried hard in May 2000 but didn’t really get close to the key final status issues). Carter, on the other hand, told his National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Brzeziński, that he “would be willing to lose the presidency for the sake of genuine peace in the Middle East,” and Brzeziński believed him.

Often speaking from his heart rather than from his advisers’ talking points, Carter repeatedly brought the wrath of the professional Jewish world down on his head, beginning just weeks into his presidency, with a March 1977 Massachusetts town hall when he responded to a question on the topic by asserting, “There has to be a homeland provided for the Palestinian refugees who have suffered for many, many years.”

Carter was only reiterating, in slightly different language, the same position he had stated during the campaign, and he qualified his remarks by saying that Israel needed “secure borders” and the Arabs needed to recognize these so that the two sides could eventually make peace. But the words “Palestinian” and “homeland” in the same sentence immediately panicked American Jewish leaders. To say the word “homeland” was to evoke, in the words of historian Arlene Lazarowitz, the creation of “a radical, PLO-dominated state that would be the first stage for the eventual realization of the PLO goal of destroying Israel.”

Even recognizing the Palestinians as a people with a right to national self-determination was enough to set off the equivalent of a four-alarm fire bell among American Jewish leaders. They had reacted nearly as theatrically when, in 1975, an assistant secretary of state named Harold Saunders, speaking to an almost empty House committee hearing, had expressed the belief that the “final resolution of the problems arising from the partition of Palestine, the establishment of the State of Israel, and Arab opposition to those events will not be possible until agreement is reached defining a just and permanent status for the Arab peoples who consider themselves Palestinians.”

The Ford administration was on its way out when Saunders made his statement, but Carter’s had just begun. Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg, a prominent scholar and president of the American Jewish Congress, would soon emerge as the most dovish of Jewish leaders and a fierce critic of the Israeli government and its neoconservative champions in the U.S. But even he objected “most vehemently” to the administration’s use of the term “Palestinian homeland,” as he insisted that it “cannot lead to peace” and would “definitely jeopardize U.S. interests.”

Carter’s plans would be made immeasurably more complicated in May 1977, by the surprise defeat of Israel’s long-ruling Labor Party by its right-wing rival, Likud, under Menachem Begin. Having rejected the original partition of Palestine as “illegal” and “never [to] be recognized,” Begin informed Carter’s NSC Middle East expert William Quandt that he would “never agree to withdrawal” from the West Bank. Deploying considerable understatement, the adviser later admitted that the Carter administration “never quite figured out how to get around Begin or work through him or work over his head or behind his back. I cannot stress to you how difficult that turned out to be.”

Carter’s top political adviser, Hamilton Jordan, misadvised the president that Begin’s election would inspire “leaders in the American Jewish community to ponder the course the Israeli people have taken and question the wisdom of that policy.” Brzezinski had also advised Carter that he might “be able to mobilize ... a significant portion of the American Jewish community” to support his plans for peace negotiations and a settlement. And this Jewish support would ease the president’s path to getting “the needed congressional support.”

Failure has met every presidential attempt to enlist American Jews to oppose the Israeli government on almost any matter, but perhaps never quite so spectacularly as in Carter’s case. Before Begin’s first meeting with Carter in May 1977, the White House received 1,552 letters addressing Carter’s Middle East policies, and 95 percent were opposed; of the 359 telephone calls on the same issue, the figure was 100 percent.

When, on October 1, 1977, the governments of the U.S. and the USSR issued a joint communiqué regarding Middle East peace negotiations to be resumed in Geneva and calling for a “comprehensive settlement” to finally resolve “all specific questions,” this negative reaction was repeated. The joint statement used the same sorts of phrases that had set off Jewish leaders in the past, including, especially, its call for the “withdrawal of Israeli Armed Forces from territories occupied in the 1967 conflict,” and “the resolution of the Palestinian question, including insuring the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people.” According to AIPAC’s newsletter, Near East Report, the phrase “legitimate rights of the Palestinian people” constituted “a euphemism for the creation of a Palestinian state and the dismemberment of Israel.” The lobby circulated a letter eventually signed by 32 senators and 150 representatives accusing the administration of “devaluing” the “principles and commitments which have guided U.S. Mideast policy during the last six administrations.” The letter concluded that the U.S.–USSR communiqué was “only the latest in a series of one-sided pressures exerted recently against Israel by the Administration,” one that “spell[ed] real danger for the national interests which the U.S. and Israel have long shared.” A presidential meeting with Jewish leaders broke up in mutual acrimony, with the Jewish leaders implying that the Polish-born Brzeziński’s beliefs were colored by antisemitism. Ignoring all protocol, Rabbi Alexander Schindler, chair of the Conference of Presidents, leaked the off-the-record contents of the meeting to the news media, thereby simultaneously demonstrating his contempt for the president and burning his bridges to the administration.

When, a month later, Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat made the surprise announcement that he wished to fly to Jerusalem to plead the cause of peace directly to the Israeli Knesset, Carter felt he had been presented with an irresistible opportunity. Yes, Sadat had upended the U.S.–Soviet peace initiative, but at the same time appeared to present a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to break the historical logjam between the two perennially warring parties. The problem was that, even as Sadat had been warmly welcomed in Israel, Begin remained committed to his stated policy. He was unwilling to stop the construction of new settlements or the expansion of existing ones; unwilling to withdraw Israeli settlers from the Sinai, or to permit U.N. or Egyptian protection for them should they stay; unwilling to acknowledge that U.N. Resolution 242 applied to the West Bank or the Gaza Strip; and unwilling to grant Palestinians a genuine voice in the determination of their future. Carter was stunned and began referring to Begin’s position as “the six noes.” Even so, he decided to take the risk of inviting Begin and Sadat to Camp David and pressing each leader to make the concessions necessary to reach a final peace agreement.

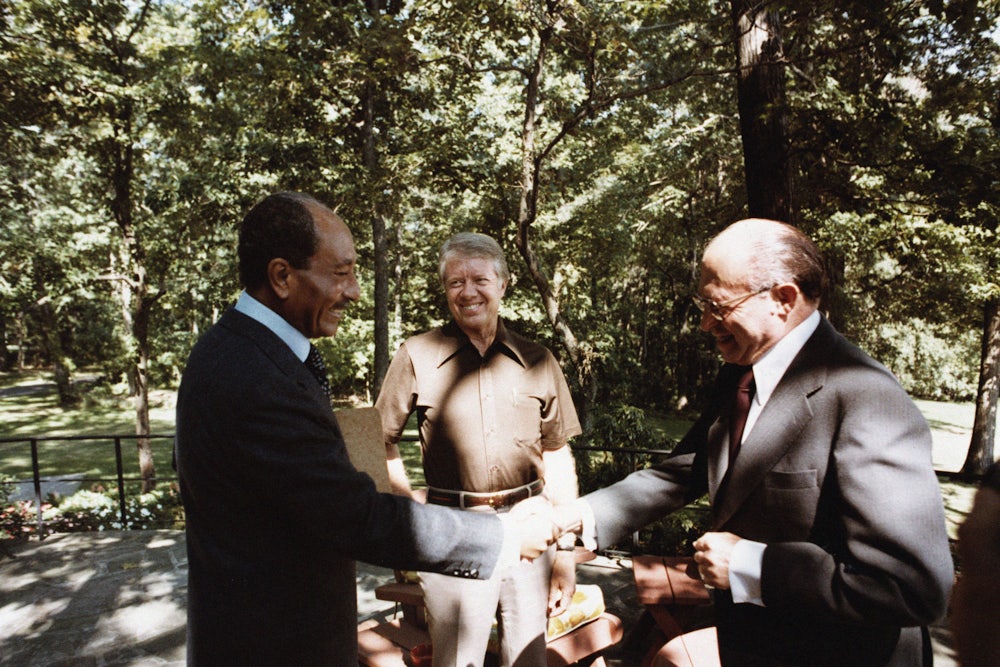

At what turned out to be a 13-day summit at Camp David, beginning on September 5, 1978, Carter found Sadat “always willing to accommodate” him, but saw Begin as “completely unreasonable,” a “psycho” who demanded “a song and dance … over every word.” Eventually, following days of dramatic blowups, packed bags, summoned helicopters, and drafted statements of failure at the ready, and fully 23 drafts of proposed agreements, Carter somehow found a formula acceptable to both sides.

Israeli defense minister Ezer Weizmann would later admit that he had “never seen a man more tenacious” than Carter had been in pursuit of the Camp David Accords. At the September 17 signing ceremony, Begin, who was far from famous for his sense of humor, paid tribute to Carter with the quip that to get to yes, the president had “worked harder than our forefathers did in Egypt building the pyramids.” Former New York Congressman Stephen Solarz, a liberal Democrat but a leading Israel hawk, called the accord possibly “the most remarkable and significant diplomatic achievement in the history of the republic.”

The most difficult of the negotiations’ many sticking points was Israel’s West Bank settlements. Carter was certain he had secured Begin’s promise to cease settlement construction immediately while final negotiations about their ultimate fate could take place. He wrote this in his diary and announced it at a post-summit joint session of Congress with Begin and Sadat sitting in the audience. But Begin felt he had meant his pledge to last only three months. What Begin thought Carter understood is ultimately unknowable. Carter would later, quite bitterly, accuse Begin of having lied on this crucial point. But the evidence is not dispositive either way. Significantly, Begin never signed the agreement that Carter and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance drew up for him that would have codified Carter’s understanding.

William Quandt would later term this a “loose end” that had been left “vague” and “unresolved,” but it would turn out to be a crucial one that risked unraveling the entire deal: Begin went home and immediately began plans to fortify and expand the settlements and soon committed to building 18 to 20 more. Whatever Carter thought he heard from Begin, the latter never veered from his bedrock belief. Peace in exchange for the Sinai was fine, but literally nothing was ever going to dislodge Israel from “Judea and Samaria” so long as it was up to Begin. As future U.S. ambassador to Israel Richard Jones would presciently observe in early 1982, when Israel had settled only a tiny fraction of the hundreds of thousands of settlers who live on the West Bank today, “the goal has [always] been to create a matrix of Israeli control of the West Bank so deeply rooted that no subsequent Israeli government would be able to relinquish substantial chunks of that territory, even in exchange for peace.” The deal Israel sought—and got—at Camp David from Egypt, thanks to Jimmy Carter, was essentially “1967 for 1948.”

Carter did enjoy a brief respite from criticism in the mainstream media, which celebrated the historic achievement and paid particular tribute to Carter’s patience and persistence. But American Jewish leaders mostly sat on their hands. They did not object to the agreements themselves, because being more hawkish than the famously hawkish Israeli leader amounted to trying to be holier than the Pope.

And they were certainly pleased that Carter and Sadat had ultimately proved willing to sell out the Palestinians, who, yet again, took another opportunity to miss an opportunity. The Columbia University scholar and Palestinian American, Edward Said, then a member of the Palestinian National Council, once told me privately that Cyrus Vance had asked him to fly to Beirut with an offer to Yasser Arafat of U.S. recognition of the PLO as the “sole legitimate representative” of the Palestinian people if the PLO chairman would agree to recognize Israel and join the talks, but Arafat refused even to see him.

Following the signing ceremony, Carter continued his dogged efforts to try to bridge the gaps between the two sides. During the repeated trips that he and Vance made to the Middle East, the problem continued to be Begin’s unwillingness to implement what Carter had understood to be his promises at Camp David. In all of these arguments, the Israeli prime minister had American Jewish leaders in his corner. When, after one December 1978 trip, Vance told reporters that Israeli intransigence was blocking an agreement, the American Jewish Committee’s Washington representative, Hyman Bookbinder, expressed his “outrage” over the “unfair accusations” and attacked what he called the administration’s “anti-Israeli campaign.” William Safire, a hard-right propagandist for Israel, titled one of his New York Times columns “Carter Blames the Jews.” Carter later complained that “in public showdowns on a controversial issue,” American Jewish leaders “would always side with the Israeli leaders and condemn us for being ‘evenhanded’ in our concern for both Palestinian rights and Israeli security.”

The Israel issue remained a political thorn in Carter’s side throughout his presidency, including especially a complicated contretemps that arose when his U.N. Representative, Andrew Young, met, in his capacity as the rotating head of the Security Council, with a member of the PLO in order to try to head off another anti-Israel resolution from coming to a vote. Carter’s resultant firing of Young, the highest-ranking Black member of his government, led to a firestorm that pitted the American Jewish establishment organizations against mainstream Black civil rights and political leaders, creating a costly rift inside the Democratic Party that has never fully healed.

In March 1980, after Young had been replaced by his deputy, the veteran Black State Department official and establishment think-tank denizen Donald McHenry, another snafu at the U.N. further intensified anti-Carter sentiment among Jewish leaders. The U.S. voted to approve a Security Council resolution condemning Israeli settlements that failed to distinguish between those on the West Bank, which was under continuing Israeli military rule, and those in East Jerusalem, which Israel had effectively annexed. Carter insisted that the U.S. had intended to abstain, owing to the Jerusalem issue, and the vote had been “a genuine mistake—a breakdown in communications.”

This was true, but the excuse did little to assuage the anger the vote provoked among Jewish leaders. Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts had been trailing Carter in the New York presidential primary in the weeks leading up to the U.N. vote, but he ended up winning it by a significant margin, rejuvenating his campaign and further weakening Carter for the general election.

New York’s loudmouthed Jewish mayor Ed Koch, whom Carter had invited to lunch at the White House after the vote, went on a kind of personal public (verbal) jihad against the president for allegedly harboring anti-Israel officials in his administration—a category in which he included not only Young and McHenry, but also, rather crazily, Brzeziński, Vance, and Saunders. He attacked the president personally and called McHenry a “bastard.”

Carter said Koch acted “like a fanatic.” But Koch’s campaign had its intended effect. Carter’s pollster Patrick Caddell blamed New York Jews’ reaction to the U.N. vote for the president’s humiliation in the primary, adding, “We’re getting wiped out. It’s almost as if the voters know that Carter’s got the nomination sewed up but want to send him a message.” If so, it was a message with implications that carried over into November 1980, when Jimmy Carter became the first (and still only) Democratic presidential candidate since the 1920s to fail to win a majority of the Jewish vote on his way to becoming what he is today: the most morally motivated of all modern American presidents and by far and away, the most dedicated to creating a lasting peace between Israel and its adversaries.