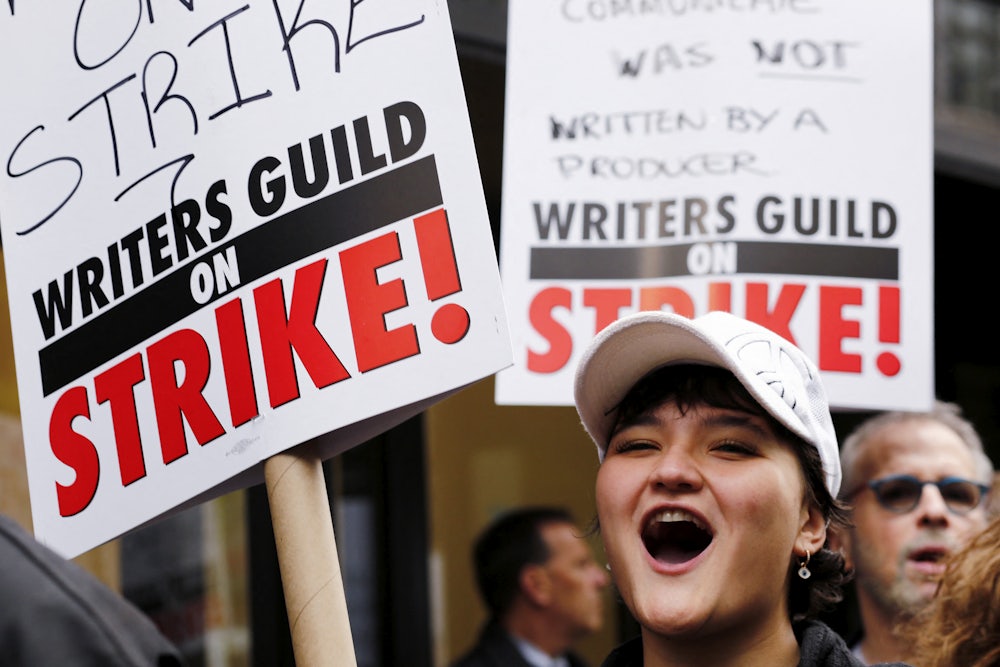

On Tuesday at 3 a.m. Eastern Time, the Writers Guild of America officially went on strike after failing to reach an agreement on a new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. This was upsetting, if unsurprising news, because, for one, I am clinically addicted to being paid. But also because it signaled that the AMPTP, the organization that represents Hollywood studios, had all but explicitly told 20,000 professional writers—the ones responsible for producing literally all the scripted content off of which they profit—that they should just quit whining.

If you’re thinking, “I’m expected to care about Hollywood writers’ financial well-being?” I hear you. The thing is, we’re not all Ryan Murphy (The Watcher, Pose, Glee). Most of us are Murphy Ryan, the fresh-faced kid from Horsefuck, Tennessee, with a full heart and an empty bank account. (For those paying attention, that’s called character development, and it’s all you’re getting for free.)

The proposals made by WGA and the studios’ responses are laid out in detail here, but essentially, writers hoped to address the shift from basic cable to streaming and adjust how we’re paid to reflect that shift. But even beyond that, the proposals were intended to make screenwriting a sustainable career—something it no longer is.

Television work, for example, is hard to get. In the past, a television writer might staff on a network sitcom where they’d be guaranteed high-paying work for the majority of a year, and supplement that income based on residual payments, presumably tiding them over until the next job came. The switch to streaming has replaced that model with shorter rooms (the length of time a writing room meets—eight weeks versus 22 weeks, for example), lower residuals, and longer gaps between jobs. Our proposal? Make rooms a little longer, residuals a little higher, writers a little better taken care of to help ensure that shows aren’t written only by promising young talent with generational wealth.

The Guild estimates that its proposals would cost the studios $429 million per year, a drop in the bucket compared with the $28 billion in operating profits the studios reported in 2021, and the $773 million eight Hollywood CEOs made in 2022. And yet on count after count, the AMPTP not only rejected our proposals, but refused to even make a counter.

It’s maddening. Equally maddening is that we’ve seen this before. Those of us who have been trying to write professionally, or be around those who do, have seen jobs disappear again and again due to corporate willingness to streamline production and minimize costs by exploiting writers.

Before I worked in television, I worked in journalism, where I enjoyed several genuinely fulfilling, joyful years of working with creative, curious people. But then, my publication’s number was called. In 2016, after numerous traumatic and high-profile shifts within the company, including the shuttering of its flagship website due to the vengeful whims of a billionaire, I left after a round of buyouts was offered to incentivize people to voluntarily fire themselves for money.

And even then, “taking the buyout” felt like an enormous privilege—Billy Zane-ing yourself off of a sinking ship before you go down with it. In the past year, journalists haven’t been nearly so lucky. In fact, since the beginning of the year, we’ve seen digital media operations undergo devastating losses. BuzzFeed announced that it’d be shuttering BuzzFeed News, laying off 15 percent of its staff. Insider laid off 10 percent. Paper Magazine laid off the whole thing. Vice will supposedly file for bankruptcy. The list goes on.

So I went to television, both because I loved it and wanted to be around the funniest people possible, but also because the medium offered stability that journalism never did. Unfortunately, soon after I arrived, I realized the stability I had observed was like starlight from many, many years in the past.

And unfortunately, on this Titanic, there’s no longer a lifeboat we can trample women and children to board—no new industry to join, no buyouts to take. Instead, we’re the anonymous, soon-to-be-dead guys who shoveled coal in the boiler room, not because we too are soon to be dead, but because there is simply nowhere else for us to go. And also because the people riding the Titanic usually love the product that they produce (a ship that moves) without giving proper credit to the ones who produce it (the guys).

In his newsletter Read Max, the writer Max Read also pointed to the similarities between the boom-bust 2010s of digital media and the current strike, noting a trend in corporate innovation that has offered an increase in profits while forsaking the quality of the products. “It would not be unfair to say ‘they’re doing to screenwriters what they did to journalists,’” he wrote, “if what you mean is that they—and it is in some cases quite literally the same Silicon Valley executives and investors!—are using technological shifts in production and distribution as an excuse to roll back labor protections and grind down writers’ share of current or future profits, regardless of how those technological shifts will affect the business overall.” Spoiler alert, Read continues: It doesn’t work!

The most obvious example of a technological shift is, of course, artificial intelligence. Even in its nascent days of widespread use, A.I. has already claimed the copywriting job of a friend who was told by a tech executive that it provides “all the options they need,” a dystopian fragment that will undoubtedly be more frequent by the week. The WGA presented studios with a plan to regulate A.I.’s use in scripts. But so far, it hasn’t been A.I. that’s been the biggest threat to writers’ livelihoods. It’s been the studios, who offer hefty paydays to a few, and unreliable, unsustainable work to everyone else. It isn’t M3GAN we should be afraid of. It’s David.

Still, it doesn’t really matter, because AMPTP rejected the A.I. proposal, offering instead “annual meetings to discuss advancements in technology.” It’s an almost laughably bad counterproposal for a thousand reasons, but most of all because no one wants to go to a meeting. They want to be at home. Watching TV. That a person was paid a decent wage to write.