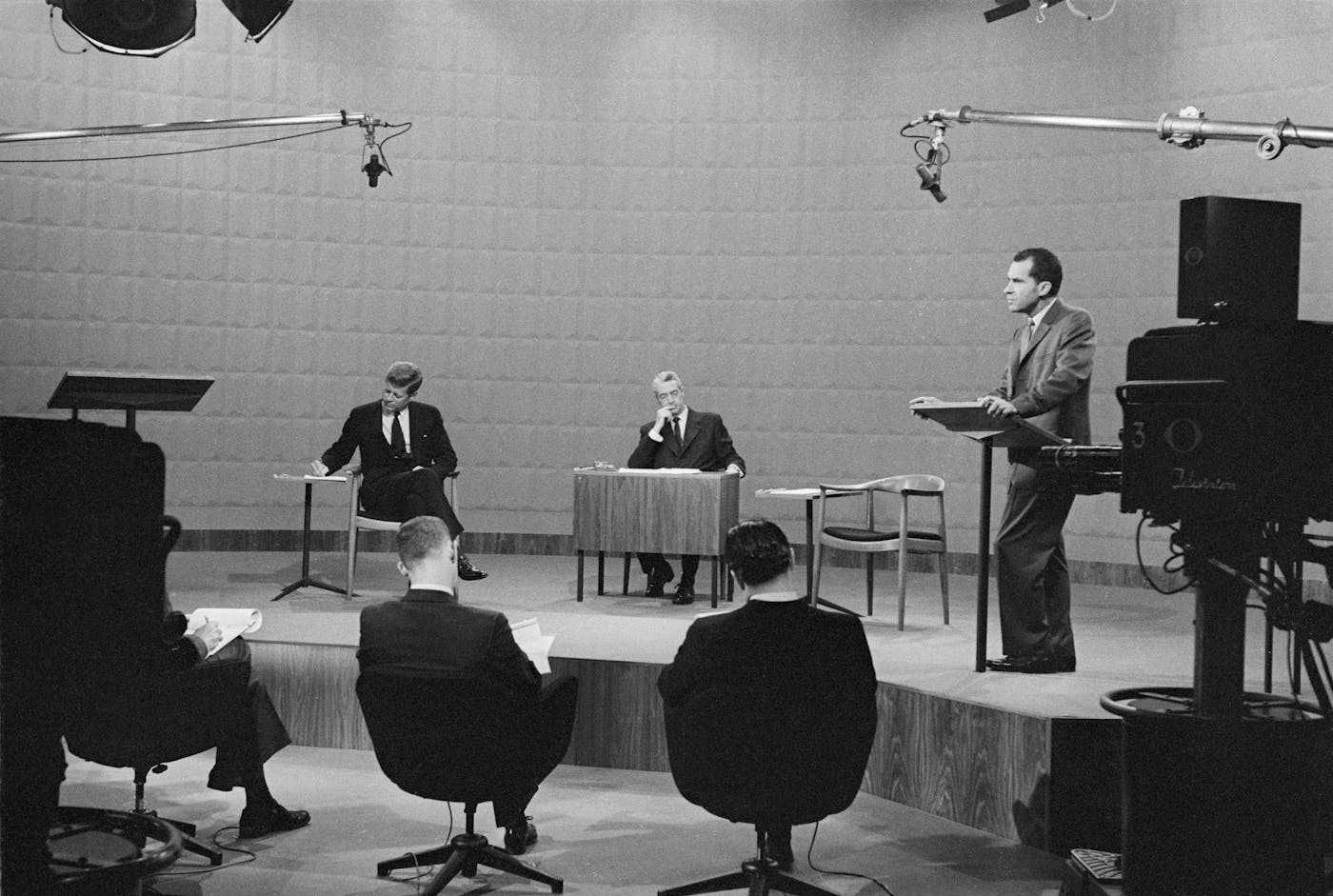

The first televised presidential debate, in 1960, began with both candidates sitting before approaching their respective podiums. Nixon was memorably not telegenic: sweaty and uncomfortable. On the chair next to him, Kennedy, with his legs crossed, appears relaxed, youthful, and handsome. In the intervening 60 years, we have come to think of JFK winning the debate by knowing how to play to the camera. But maybe the chairs also helped: They were Danish.

In fact, they were Hans Wegner’s famed round chairs: the ultimate symbol of midcentury sophistication. The chair was spartan and simple—one big curve that could easily be picked up and moved (the back was a natural handle), like many other streamlined Danish products. The design was apt for postwar America: democratic looking in its simplicity and use of natural products but, without bulk and ornamentation, a sign of the future in which form follows function. As one magazine writer from the time described Danish furniture: It was “human and warm” unlike the “totalitarian” aesthetic put forth by International Style.

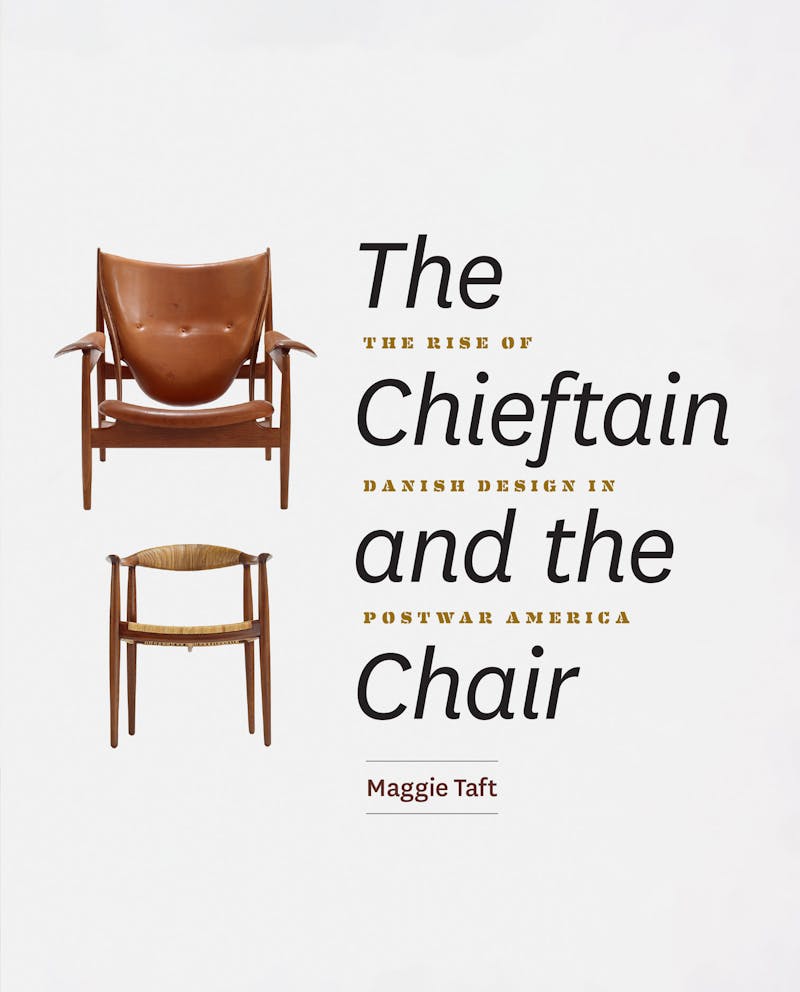

The Wegner chair is one of two pieces that Maggie Taft considers in her new book The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America. The other is the Chieftain chair designed by Finn Juhl. Together, the two seem to capture two different forms of aspiration. While the round chair is understated and unassuming, the Chieftain, as the name suggests, is the boss’s chair for relaxing: large, sunk deep down to the floor, and featuring curved black leather arm pads on the horizontal rests that form a right angle with the back of the chair. Thin teak wood diagonals support the large leather seat creating what Taft calls “a floating effect.” The two chairs were also created by very different men: Juhl was an architect with a coveted degree from the Royal Danish Academy and a Dean at a local college. Wegner apprenticed as a cabinetmaker before making his way to Copenhagen to be a designer; he had more in common with the artisans who made the chairs than with the illustrious architects who taught industrial design.

The most famous Scandi furniture now comes in flat packs, bought cheaply with a stop-off to the cafeteria for a helping of frozen meatballs with lingonberry jam. But the original appeal of Danish furniture was deeper: It promised craftsmanship at a time of ramped-up assembly line production and the pared-down aesthetic of natural wood when the space age look of new materials was ascendant. As Taft shows, these qualities were closely linked to Danish political culture in the postwar years—to its progressive thinking, vibrant democratic principles, and above all its emerging welfare state.

American consumers had

begun to take an interest in Danish designers as early as the 1920s. The

Brooklyn Museum showed Danish art and interior design in 1929 and Copenhagen

furniture makers were involved in the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. But it was

after World War II that Danish furniture really became popular in the United States. The

market for high-end furniture was somewhat limited in Europe, where countries

ravaged and depleted by war were slowly building up from the rubble. Danes, and

other Scandinavian furniture retailers, sensed an opportunity in the U.S., where

disposable income flowed more freely. Postwar America was hungry for couches,

chairs, tables, and bureaus to stick inside the many Levittown-like

developments springing up.

Most of the furniture conformed to the principles on display in MoMA’s 1949 competition for low-cost furniture design. But wealthier buyers also began to collect pieces to outfit modernist homes. Taft uses the examples of Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe houses: International Style homes with angular lines and spartan interiors, where the owners set off this severity with the warmth of Danish furniture. While the Danish chairs are considered part of midcentury modernism, they are at odds with much of the aesthetic: They are simple but not spare, homey rather than industrial, and deriving from nature unlike the plastics, steel, or concrete used in modernist or brutalist architecture. They were a comfier addition to the slightly sterile and cavernous interiors of modernist houses.

While some of the furniture went to affluent residences, a large portion also ended up in posh restaurants and corporate headquarters, custom-built by noted architects. Often this purchasing was a minor act of rebellion against the grandiose rigidness of modernist design and a desire to have something natural seeming in otherwise streamlined spaces. A 1947 Danish government film hyping the crafts economy quoted Finn Juhl: “Furniture should be so made that you get the urge to feel the wood … that warm and living character that causes one’s fingers to tingle.” As life became more regimented and a sense of bureaucratic ennui set in, even for the successful new white-collar workers living the life of a John Updike novel, furniture that looked natural and timeless was a relief from a world galloping into the Space Age.

Why did Americans turn to Scandinavian designers specifically? Economic conditions in Scandinavian countries were ripe for a flowering in design: They had excellent art schools, a strong craft tradition, well-paid specialist production, and a welfare state willing to subsidize some areas of manufacturing. As well as, less admirably, a pseudo-colonial relationship with Thailand that guaranteed cheap teak (until it was terminated in 1960). While Denmark was not known as a major colonial player, except perhaps to people from Greenland, its global influence provided unique materials for high-quality furniture.

Praise of Danish design mounted quickly in the U.S. through exhibitions, magazine articles, and word-of-mouth. Taft relates how Wegner was approached by a members-only club in Chicago in 1949 hoping to acquire 400 chairs, a number far beyond the capacity of the Copenhagen workshop that produced them. Danish chairs became a bragging right with devotees memorizing the shapes and mentally cataloging the available colors of upholstery. The appetite for Scandi furniture was so voracious that knock-offs proliferated. Genuine producers began affixing metal plates, stamps, and brands to the underside of their furniture. One would not be surprised to see their dinner guest surreptitiously peering under the Chieftain looking for where the wood had been marked by a hot iron in the Danish workshop.

The heyday of artisan furniture, however, was brief. Keeping production in Denmark, or even in Scandinavia, did not last long. In 1951, Juhl began designing for Baker, a furniture company from Michigan; the idea was to sell his designs to a larger mass market by scaling-up production. Yet it was never clear how the level of quality could be maintained outside of the Scandinavian welfare state with its unique compromises between government, industry, and labor. In an American mass market, it would be difficult to make elegant joinery using Fordist production techniques (and to pay artisan wages to assembly line workers). As the scale of production increased, it was more difficult to maintain the myth of “Nordic naturalness” and wood forms that represented a closeness to nature. In fact, even the teak was being supplanted by razor-thin slices of rosewood pasted onto furniture facades.

Meanwhile, loose legal protections for furniture design meant that fakes and copies proliferated. Well-heeled tourists in Copenhagen could visit the immense furniture showroom Den Permanente near the central station to see authentic Juhls and Wegners, but they could also saunter over to Tidens Møbler, a store that “offered copies that looked nearly as good” at a steep markdown. “And when exported to America, both the real thing and the copy could legitimately be labeled ‘Made in Denmark.’” Even more alarmingly, American companies were making fake Danish furniture of lesser quality and at lower prices. Some of these businesses still exist today because of their successful foray into midcentury design.

At the same time, counterfeiting was also responsible for a big part of the popularity of Danish furniture. Knock-off versions made design truly widely available. The imitation versions of the furniture were more accessible and also more global: Already in 1955 copies were being made in Taiwan, Mexico, and Yugoslavia. Around the world, designers were churning out “Danish” interior design.

Danish furniture makers spent the 1960s fighting for copyright recognition at home (granted by parliament in 1961) and in the U.S. (approved by the Federal Trade Commission in 1968). But they were also conducting a battle over taste. Taft shows this was often due to cultural differences: Danes wanted furniture for lounge rooms, Americans wanted things to watch and store their TVs on. Danes had a history of interesting space-saving experimentation: designs included “multipurpose furnishings called forvandlingsmøbler” such as “a storage unit that doubled as a minibar or a two-seat sofa that converted into a daybed.” But in increasingly affluent suburban America the point was to fit out larger homes, not to economize.

By the Nixon-Kennedy debate of 1960, the heyday of Danish (and Scandinavian) design was coming to an end, and pieces from a golden era were already being collected and curated. The same year, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York featured the Arts of Denmark: Viking to Modern exhibition, which was both a celebration of cutting-edge design as well as a tribute to the Scandi welfare state and its social goals that were both generous yet not communist. The exhibition stressed the importance of artisans and small businesses rather than state-directed (or private) factories despite the fact that this small-scale manufacturing was quickly becoming economically untenable in Europe and America.

But the free market had the last laugh: Most designers lost their niche businesses to knock-offs well before copyright protection came into effect. What happened then, a story not told in the book, was the shift to the warehouse, flatpack furniture of IKEA (from nearby Sweden). This trend demonstrated the demand for disposable furniture, produced cheaply abroad, and bought in large suburban box stores. Most people never had the money to buy a Chieftain chair, but the pared-down Ekenäset is $250 at IKEA.

Perhaps because of the IKEAization of the global furniture market, original midcentury pieces have grown in popularity. They represent not just a different consumer ethic of buying something for life but also a belief in craftsmanship. They come from a world in which furniture makers could still afford to live in Copenhagen, rather than cutting particle board and bagging screws in Binh Duong Province, Vietnam. Though most consumers may not be aware of it, these pieces were carved out of the basics of social democracy, which brought together living wages, job permanence, and the sense of producing a meaningful product that will not be quickly torn apart and binned when moving day comes.

Of course, the appeal may not be all nostalgia. The faux egalitarian nature of Scandinavian design, despite the fact that it was mostly purchased by elites, is also perfectly suited to an age of hyperinequality. The chairs are exactly the tasteful expensive objects that look homespun and quotidian to those who have not seen their $5,000 (per chair) price tag. No assembly required.