America loves a therapy story. The Shrink Next Door, based on the podcast of the same name, tells the true story of a therapist who took over a patient’s life so thoroughly that he essentially became his therapist’s servant. Shrinking is a light-hearted dramedy about a therapist who pushes the boundaries of traditional therapy, inviting a patient to live in his house. The Patient stars Steve Carrell as a therapist who gets abducted by a serial killer patient who wants him to talk him out of killing again. There’s the long-running In Treatment, which began in 2008 and had its most recent episodes in 2021. And of course, there are the shows that invite us into actual therapy sessions—Couples Therapy or the podcast Where Should We Begin with Esther Perel.

America also loves a cult story. There’s The Vow, about the NXIVM cult and its leader Keith Raniere; there’s Wild Wild Country, about a cult that built a supposedly utopian city in the desert of Oregon; Heaven’s Gate: The Cult of Cults, about the infamous UFO cult that ended with mass suicide in 1997; Jonestown: Terror in the Jungle, about the cult that led to mass murder-suicide in 1978; The Way Down: God, Greed, and the Cult of Gwen Shamblin, about the Remnant Fellowship church and the leader who preached weight loss as a spiritual assignment; Stolen Youth, about the cult at Sarah Lawrence college—and many, many more.

I am an avid consumer of these stories; I firmly share America’s fascination. I have often thought that therapy stories hold interest because they invite us into intimacy with other humans that we don’t often access: an active examination is at play, human beings airing their vulnerability, their mistakes, and their hopes. Cult stories seem to exemplify the ways humans crave belief systems: They show how easy it is for people to give up their will, and perhaps offer viewers a chance to declare themselves exempt, superior—that would never happen to me, I am not so susceptible.

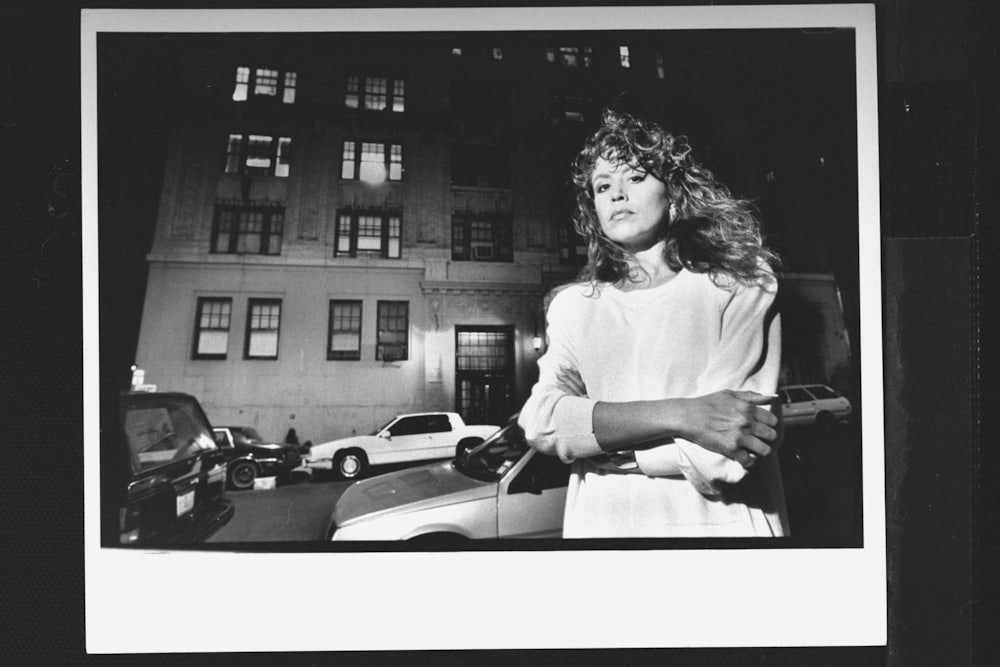

Alexander Stille’s book The Sullivanians is a therapy story and a cult story combined. It tells the story of a group formed on the Upper West Side of Manhattan beginning in 1953, professing a radical form of psychoanalysis that preached against the nuclear family and encouraged an alternative lifestyle. Over the years the group included Jackson Pollack, Judy Collins, critic Clement Greenberg, and novelist Richard Price, and at its peak had around 300 members.

The story has the same features as many astonishing cult stories: coercion, sexual abuse, child neglect, extreme paranoia, disowning of families, theft, and kidnapping. But one of the most astonishing aspects of this story is the way it shows the practice of psychotherapy blurring into a form of social control. Perhaps, it suggests, the things that draw a person into an insular community are the same things that many of us also seek in therapy: to find support, to be offered a reflection of ourselves (which, in too many cases, means an ugly picture, as we believe ugly things), and to defy the terribly unsettling fact that we have no control over anything.

The Sullivan Institute for Research in Psychoanalysis was officially founded in 1957 by Saul Newton and Jane Pearce, then a married couple with two children. Both had worked at the William Alanson White Institute, one of New York’s leading psychoanalytic institutes in the mid-1940s. Pearce, Newton’s fourth wife, was a psychiatrist doing her psychoanalytic training, while Newton, who had no formal training as a therapist, worked in the bursar’s office.

The White Institute, Stille writes, “had a complicated relationship with the starchy Freudian orthodoxy that dominated the field.” Harry Stack Sullivan, one of its founders, was a hero of Saul Newton’s. Sullivan and his colleagues argued, in contrast to the Freudian focus on internal struggles, that therapists must understand patients “in relation to the other people in their life,” a product of interpersonal relations. The White Institute admitted so-called lay analysts, including Erich Fromm, who had a Ph.D. but not an MD. The Sullivan Institute, in turn, took this still further: Saul Newton never had any degree that would qualify him as a therapist, and others who trained and practiced as therapists in the group didn’t even have college degrees.

Sullivan died in 1949. Despite his argument that the “self-system” was repressive and that the way out was through relation to other people, Sullivan had stopped short of arguing anyone should break free of the nuclear family and monogamous marriage; Newton and Pearce felt that after Sullivan’s death, “the White Institute did not have the courage to explore the full implications of his ideas.” They wanted to go further than Sullivan ever had to combat the orthodoxy of psychoanalysis. They founded the Sullivan Institute “to test a specific idea of human nature: that nature was nothing and nurture was everything.”

Their practice was based on the idea that people should follow their desires rather than adapt or conform to what their parents or society expected of them. Parenthood for the Sullivanians (Stille uses this term to refer to the group born out of the Institute, though he acknowledges that no official term exists), “was a kind of death trap from which both parent and child needed to be liberated.” The nuclear family was “the basic unit of capitalist production,” and psychoanalysis as it worked under Freud was only serving to perpetuate the status quo. Newton and Pearce “believed that therapy could carry out a personal revolution in each person by offering a patient the opportunity to reach for the ‘infinities of growth.’” This growth was attainable by means of regular therapy and by practicing free love and unattachment to any single other person, including one’s offspring.

Sullivan had championed an idea called “chumship” among his patients, encouraging his most troubled patients and those with schizophrenia to live together in all-male group housing, suggesting that community could help with mental distress. Newton and Pearce took this idea further, arguing that their patients could break free of monogamy and the nuclear family by living together in same-sex apartments and avoiding any single “focus” on any one person, including their children, whom they most often sent away to boarding schools. The therapists lived in the group apartments alongside their patients, and they were frequently sleeping with them. There was a “training program,” where specially chosen patients were invited to train to be therapists; it is unclear what the parameters of this training were, and it seems it was mostly a way to create a hierarchy. In therapy sessions, patients were encouraged to break ties with their families, who were portrayed as evil, the source of all ills.

Patients filled datebooks with sexual encounters and study dates, along with friendship dates, group classes, and “sleepovers”—often with same-sex friends. Every weekend there were parties, “which invariably ended with everyone pairing off and going to bed with someone else. To do otherwise was seen as a refusal to grow.” It is easy to see how appealing all of this was: In the late 1950s and the ’60s, when the group was growing, rebellion against societal strictures was becoming more popular in leftist circles, and the Sullivanians offered a ready-made community that could satisfy all your desires (sexual, political, social) at once.

Many of the famous people who passed through the group play only cameo roles in the overall story, though the group left lasting marks even on those who were briefly enmeshed. Judy Collins, for example, who remained in Sullivanian therapy for 15 years, wrote about it in her memoir: “I sure got a lot of mileage out of the Sullivanian belief that alcohol was good for anxiety and that having multiple sex partners was a political statement and a healthy lifestyle … Only later, after I had left them, did I realize I had fallen under the spell of a cult.”

Michael Cohen, who joined as a young man in 1972, was drawn much deeper into the group. He had lost both of his parents by the time he graduated from high school, and he initially entered the group because of its revolutionary politics and because it provided him with friends and an active sex life. Cohen began therapy with Joan Harvey, who in 1972 was Saul Newton’s fifth wife and one of the group’s leaders (Pearce, by this point, was marginalized in the group). Harvey told Cohen repeatedly that he could never survive without therapy—this was one of the group’s most often repeated lines. Without the group, “he would wind up in a mental hospital, or dead, or in prison.” He believed it.

Harvey, who was Jewish, ridiculed Cohen’s family as “fat, ugly, stupid Jews,” and encouraged him to break off all ties with his one surviving sister (who lived in Israel), which he did. Sullivanian therapists carried out this routine over and over with others—patients wrote letters to break off ties with family members, and therapists watched from the window as patients put their letters in the mailbox. Many members didn’t speak to family for many years; many had parents die while they were in the group, and never saw them again. When Cohen’s sister called, he was “instructed to tell her to ‘fuck off,’ that she was a ‘fascist Zionist pig.’” All of this Cohen did, as he trained to become a therapist just like Harvey, encouraging others to cut off ties with their families in turn. He stayed in the group for more than a decade.

Like Cohen, DeeDee Agee, daughter of writer James Agee, was young when she joined. In 1971, she was 24 years old, married, and with a 2-year-old son, living an isolated and unhappy life in upstate New York. Her husband was an alcoholic who was frequently away for work. Thanks to therapy, she left her husband and moved into a group apartment, breaking with a family pattern that had repeated over three generations—early death, alcoholism, and a female existence built around the fate of a man. After three years of therapy, her therapist encouraged her to send her son, then 5, away to boarding school. She was told, as were many others, that she was so dangerous to her son that she shouldn’t visit him or spend vacations with him.

Eventually, she lost her son in a custody battle with her husband (the judge: “plaintiff … spends more time with her therapist than she does with her son”). In 1982, DeeDee Agee had another child via what the group called a “sperm pool,” whereby a woman would sleep with multiple people during her ovulation period, and the leadership refused her access to the infant, insisting that her breast-feeding was creating dependence in the child, which was ultimately bad for both mother and baby (it should be noted that members of the group’s leadership were always allowed to hang on to their children and used much of the money they pilfered from their patients to send them to fancy Manhattan private schools).

Over the decades, the group became more and more insular, more and more leader-driven, more and more abusive and cult-like (although to this day some former members bristle at the classification). On a few occasions the group used violence to defend its turf: In 1985, when the recent college graduates who lived next door to one of the group buildings refused to remove some paint they had spilled on the building, the group broke in and attacked their place, smashing dishes, furniture, sinks, and toilets, and “when one of the young men came over to protest what had happened, one of the men from the group pulled him into the lobby and hit the boy so hard he broke his own wrist.”

When the nuclear accident happened at Three Mile Island in 1979, the whole group flew to Florida because the leadership told them New York City was unsafe. During the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, new restrictions were put in place, members were disallowed from sleeping with people outside of the group, as well as from eating any food not prepared by a group member. The Sullivanians became more and more hierarchical, with Saul Newton and the leadership (his fifth and sixth wives and the fifth wife’s new husband, a long-time Sullivanian therapist) enjoying rights denied to other members and buying real estate with members’ money, while members worked multiple jobs to be able to stay in the group.

Saul Newton appears to have abused his patients over the entire course of the group’s existence, demanding oral sex during therapy sessions, fondling young girls, and as the years went on, erupting into maniacal rages, all the while taking money from his patients. By the late 1980s he was showing signs of dementia, and his demands were even more out of control; his sixth wife and fellow group leader Helen Moses, no longer interested in sex with him, would send him young women to occupy him. In one particularly horrifying story, Newton forced a young group member to move out of her apartment when she was six months pregnant, the stress of which caused her to deliver her baby prematurely. Upon returning from the hospital, she reported to therapy, and Newton made her perform oral sex on him. Instead of having an orgasm, he defecated in his pants.

The group’s attitude toward the nuclear family has left a long trail. In 2019, dozens of kids who were born in the group, never knowing who their parents were, banded together to share genetic data. Major custody battles ensued—Stille takes a lot of material from court transcripts—including one case in which a father who left the group spent years fighting for custody of his twin girls, only to find out many years later that he was not their biological father at all. Michael Cohen, who participated in two different “sperm pools,” learned he had two biological children he hadn’t known about. Stille asks him how it was possible that he could have had sex with ovulating women and then not even consider that their offspring could be his.

In one of these encounters, Cohen participated willingly, with fond feelings and a genuine desire to help; in the other case, the experience was a horror. He was made to sleep with Helen Moses, Saul Newton’s sixth wife, under extreme duress. Cohen’s therapist, Joan Harvey (Newton’s fifth wife), pushed him to do it, but Cohen resisted; then Newton himself intervened, screaming, threatening Cohen, saying he would kick him out of the group if he didn’t. Cohen, afraid “he would be a homeless, penniless, friendless, unemployed twenty-three-year-old with no family and no direction,” eventually acquiesced, but was so disturbed he couldn’t perform until he calmed himself with drugs. Years later—he was able by then to call it rape—it shocked Cohen to realize this happened within a year of his entering the group, and yet, he still went on to become a true believer in the group’s philosophy.

Stille’s

book and the story of the Sullivanians raise questions about just what we are

seeking when we go to a therapist for help. I know I have been

frustrated by therapists who offer no solutions or advice, who simply validate

my confusion. Is that all you can do to help me? There is something inherently

unsatisfying in responsibly practiced therapy and therapy narratives, which are

often open-ended and undirected (some of the popular depictions play with this

frustration: In Shrinking, for instance, the therapist breaks

traditional rules to tell his patients what he actually thinks). Perhaps many

of us would like our therapy to be more directed; we would like, in fact, to be

told what to do.

The story Stille tells shows the risks of handing over control of one’s life. A therapist tells a female patient to “shut your mouth and open your legs.” Therapists were forbidding new mothers to breastfeed their children for more than 20 minutes at a time, then for no more than seven, and then forbidding them to see their babies at all. That the group met its end when brutal custody battles in the 1990s exposed many abuses is a rather tidy irony. Being told what to do often does not solve our problems. Forcibly cutting off families, removing children from their parents, bucking the nuclear family with violence only led to more conflict—none of it examined.

As Stille shows, many of the former members struggled for decades after the group dissolved with the choices they had made and with the legacy of those choices. DeeDee Agee, in a letter to her son 25 years later, wrote, “We believed that we are all more alike than different, that nurture trumps nature every time, and it wasn’t such a big leap to the notion that it was of no account who your biological father was.” Replying to her son’s suggestion to move on from what happened, she added, “The past is alive in us always, all the more so when we try to ignore it or forget. It calls for attention like a phantom limb. Sometimes it’s more real, more potent than the present.”

It seems to me that it’s in the space between these two assertions that many of our struggles lie. We are many of us haunted by the past, even as we try to tell ourselves it doesn’t matter, that it is the present that matters most. We are haunted, too, just as much by the questions we don’t know the answer to as those we do. Even if nurture trumps nature, we still want to know who we are in every way that we can; we still want to understand our origins, and why we make the choices that we make, especially when those choices lead us down bewildering paths. Maybe this, actually, is what we need therapy for.