In late May, just six months before the election to decide his successor, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner penned a statement denouncing yet another state bill targeting his ability to govern. Republicans had already come for the region’s school board, for its elections administrator, and even, in effect, for its future election results. The latest bill, which concerned a long-running firefighter labor dispute, “might play well for some politically,” Turner wrote, “but it will not bode well for Houston and its financial future.” He continued from City Hall: “This mayor will turn over to the next mayor … a city that is in [a] healthy financial state. It’s up to the next mayor to maintain it.” Turner was directing a jab at the bill’s author, state Senator John Whitmire, who is the front-runner to succeed him—and a fellow Democrat.

The bill, which Governor Greg Abbott signed into law in early June, mandates binding arbitration between firefighters and the city, effectively ending the grueling six-year conflict during which the first responders worked without a contract. It also buttresses public workers’ collective bargaining rights by ensuring firefighters’ right to negotiate and come to a resolution, rather than struggling to get a word in edgewise over whatever the mayor wants.

That Whitmire, a well-known conservative Democrat and the longtime chair of the state Senate Criminal Justice Committee, would champion such a law may seem surprising given his hard-nosed reputation. (In 2021, Last Week Tonight With John Oliver shared a clip of Whitmire explaining the “real solution” to the lack of air conditioning in Texas prisons, where heat has killed more than 270 people since 2001: “Don’t commit a crime and you can stay home and be cool.”) But he’s a union member himself, with a long history of backing labor in the state legislature. Conversely, Turner, who ran for mayor on a progressive platform in 2015, and is term-limited out after winning reelection in 2019, has behaved like a classic union-busting CEO in office: He threatened layoffs in the hundreds, claimed the city didn’t have the money to meet union demands, and circumvented negotiations entirely by unilaterally enacting concessions, including incremental raises.

The new law, and the resulting spat between a progressive-talking corporate Democrat (Turner) and a labor-embracing conservative Democrat (Whitmire), has exposed a left-liberal fault line running through Houston, a newly solid blue beachhead in the Lone Star state. The fight may not only be key to the upcoming mayoral race but also to the city’s future. In Texas, the state government and decades of austerity have weakened unions, constricted city budgets, and neglected a laundry list of eroding infrastructure, leaving some Houston liberals to feel they must decide which reforms are worth the price tag, and which they can live without.

If Texas’s expansive modern prison system, renowned for its cruelty, has a single architect, it may well be John Whitmire. With the support of then-governor (and revered liberal paragon) Ann Richards, he overhauled the entire penal code in 1993, resulting in harsher, longer sentences for violent and nonviolent offenders. (Whitmire, now the dean of the state Senate, had already held the seat for 10 years at that point.) George W. Bush, the next governor, cheered Whitmire on as he continued his crusade. The prison population nearly doubled in just five years, and the number of its prison beds grew apace, eclipsing those even in California, a state which then had 70 percent more people. With a $2.5 billion price tag, the Texas prison construction spree was one of the largest public works projects in the country.

It took more than a decade for Whitmire, and even some Republicans, to realize their strategy was untenable. Despite the construction wave, prisons were all but full amid a 2010 budget crunch, requiring either further construction or cheaper alternatives to incarceration. Whitmire changed tacks, working to shore up the parole-and-probation-to-prison pipeline, which then accounted for around two-thirds of incarcerations. But despite some rollbacks and a trickling decline in the state’s prison population, Whitmire’s tough-on-crime bona fides remained intact. He has, for example, held his chair on the state Senate Criminal Justice Committee on and off for three decades, even as all of the other Senate Democrats were forced to relinquish their gavels. (The Texas legislature is officially nonpartisan with the lieutenant governor making committee assignments, which can lead to members of the minority party leading panels, a practice that conservative activists have managed to eliminate in recent years, with the exception of Whitmire.)

As a result, Whitmire has tried to have it both ways on crime. He uses his prior position bolstering Texas’s punishment system to burnish his image as a firm, uncompromising justiciar, doling out grueling sentences to so-called career criminals. “Sometimes, I think some of my colleagues and other elected officials need to be held up at gunpoint,” Whitmire wrote in a 1995 Dallas Morning News op-ed recounting his family’s own such experience. “Then they would take this as seriously as I do.” But he also uses his later shift to a decarceral, smart-on-crime approach—impelled, mostly, by budgetary shortfalls—to claim a mantle as a liberal reformer.

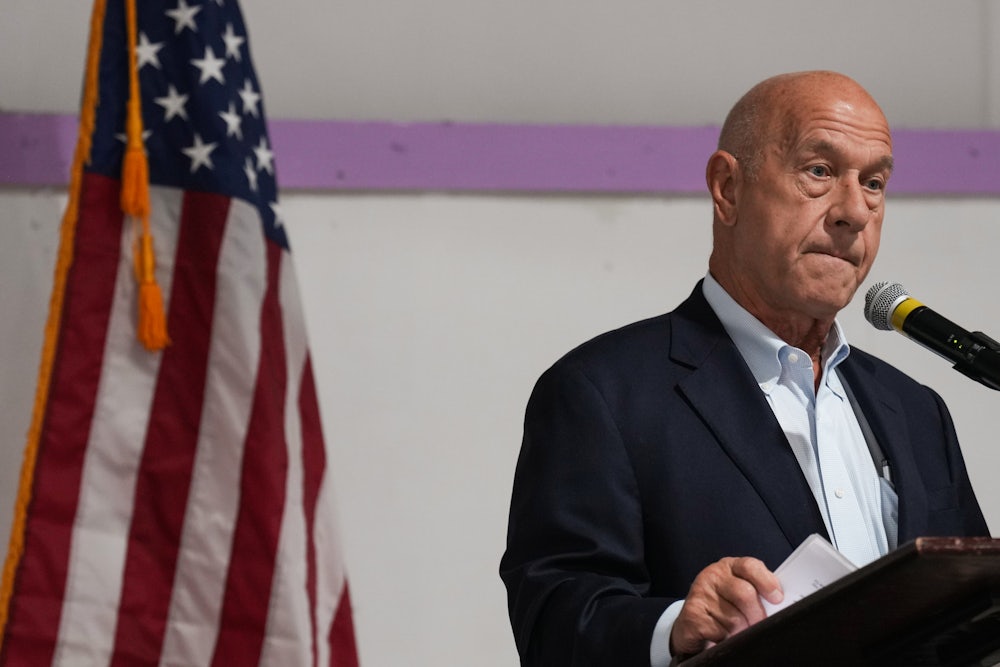

Houston’s mayoral race is officially nonpartisan, but several Republican megadonors, including Houston Rockets owner Tilman Fertitta, joining Whitmire at his 2022 campaign launch spoke volumes about which Whitmire iteration was running. Their desire for a tough-on-crime (but easy on ethics) mayor seemingly outweighed the (D) that has for decades accompanied his name. His campaign war chest holds some $10 million, with donations from Fertitta, oil and real estate interests, and police associations—but also the local Teamsters and firefighter unions, and the AFL-CIO. “The bottom line is we have a crime issue in Houston,” Whitmire declared at his announcement. “I want you to tell the firemen and the policemen that help is on the way. I want you to tell Houstonians that help is on the way.”

The Gulf Coast Area Labor Federation, part of the AFL-CIO, gave Whitmire an early endorsement, meaning that more than 80 percent of the union federation’s 300 delegates voted to endorse him. “He clearly showed his understanding and commitment to union values.” Jay Malone, its political and communications coordinator, told me. “The big concern that is at the forefront of all of our decisions is around the city budget and its potential impacts on city employees. There’s a long-term structural imbalance and, at some point, the next mayor is going to have to make a decision that has the potential to impact thousands of city workers. We want to make sure that the next mayor is someone who is going to prioritize those workers.”

The decision to which Malone referred involves the city’s revenue cap, a proposition anti-tax activists helped pass in 2004 that limits the amount of property taxes Houston may collect each year, forcing the city to reduce its tax rate when property values increase. It’s a rigid austerity measure of the type that became popular nationally in the 1970s as white suburban families, many of whom had fled the urban core, received services through their neighborhood homeowners association instead of the city proper. (In 2019 the state legislature enacted a similar law limiting how much local governments may increase their property tax revenue without voter approval.) Not so coincidentally, since the measure passed, many of Houston’s wealthiest neighborhoods have created their own Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones, which reserve a portion of property taxes to be spent only within their boundaries, effectively allowing them to hoard their accumulated wealth and avoid sharing with the rest of the city. The revenue cap has saved the average Houston homeowner a cumulative $950 over the past decade, the Houston Chronicle reported, but it has cost the city some $1.8 billion that could be spent on roads, parks, and, yes, firefighters’ salaries.

Financial projections from last year’s budget forecast deficits of anywhere from $114 million to $268 million during the next mayor’s first term. As property values continue to increase, the thinking goes, the city is nearing a fiscal cliff, and public workers’ jobs could be among the first round of sacrificial offerings. Unions, wanting to prevent that, need a powerful ally in the budget fight, and Whitmire, whose political acumen and deep pockets make him a favorite in the race, seemed a natural choice. (Notably, the AFL-CIO endorsed Turner in his 2015 run, but declined to do so in 2019; it’s possible that backing an unproven progressive candidate this year, only to be potentially burnt again, was also part of the organization’s calculus.)

Houston’s mayors have long lamented that the revenue cap ties their hands when it comes to progressive measures. But Bill King, a Republican-leaning businessman who wrote a book titled Unapologetically Moderate and ran against Turner in the past two mayoral cycles, called the complaint “complete and utter bullshit.” King, who says he’s given Whitmire and other mayoral candidates policy advice and expects to endorse the state senator “at some point,” contends that the city is flush with cash from federal Covid-19 grants and other revenue sources, including utility bills. The city has more than $400 million in reserves, the strongest it’s been in decades (the healthy financial state to which Turner referred). “There may be some employees that need to be laid off, but that’s a completely different issue,” he said.

Rather than real budgetary issues, King argues, the long-running city-firefighter labor dispute results from Turner’s, shall we say, unique disposition. “He is very thin-skinned,” King said of his two-time opponent (“We get along fine,” he added, “we see each other occasionally and chat”). So when the firefighters made strong demands for better pay in 2017, Turner took it personally. “They’ve been in a pissing contest ever since,” King said.

Others doubt that a mere personality issue is holding Turner back from enacting his original progressive vision so much as a lack of political will. Longtime observers remember Turner the 2015 candidate advocating for workers’ protections and affordable housing before failing to deliver as mayor. Measures such as paid sick leave languished under his administration, and Turner faced scandal after scandal delaying affordable housing construction—not to mention the mountain of evictions that occurred under his watch during the pandemic while he refused to enact a local moratorium.

Rob Block, a rank-and-file member of the firefighters union, who self-describes as “not Whitmire’s biggest fan either” and still isn’t sure who he’s voting for, also doubts Turner’s budgetary reasons for opposing the mandatory arbitration law, which he calls “a pretty standard union-busting narrative.” And yet, he marvels, “somehow people still view his position as progressive and the labor position as reactionary.” Even those who expected more from Turner’s administration have their problems with Whitmire’s move; one longtime Houstonian, who works in the progressive community but asked to remain anonymous for fear of their employer being drawn into the squabble, told me, “The firefighters probably do deserve a raise, but I know each dollar spent on the fire department is a dollar that can’t be spent on roads or parks or other things across the city.”

Meanwhile, the city has diverted millions in crucial funds away from drainage infrastructure and into its general fund, according to West Street Recovery, a local nonprofit formed in response to Hurricane Harvey’s devastating floods. (In late June, facing substantial pressure from residents, Turner added $20 million to a fund for drainage projects, which one Houstonian likened to “crumbs” compared to the funding needed as hurricanes become more severe due to climate change.) “No one likes to say they have no power like these Texas center-left” politicians, said Ben Hirsch, the group’s co-director. “What we say as a community group is it’s very clear you have more power than us, and we’re asking you to use it.”

King, the businessman who ran twice against Turner, believes there’s a simple reason some Houston liberals oppose Whitmire’s arbitration law: The firefighters “are overwhelmingly Republican.” The anonymous Houstonian with whom I spoke argued it was less due to their politics and more the budget tradeoffs. “Right now I don’t see any fires blazing out of control,” the resident said, “but I do see plenty of potholes that need to be filled and sidewalks that need to be built.” In his view, if the city gives the firefighters what they want, solutions to every other problem will have to go unfunded. Block, who is also a former candidate for the Texas state legislature, has a different take: “Houston’s not a city that in recent history has had a lot of labor movement stuff.” Without that strong voice for workers, he said, “people just don’t have the expectation that the government is going to make changes for working people.”

“You look at places like Chicago where they just elected Brandon Johnson,” Block added, referencing the recent progressive win in the country’s third-most populous city. “That’s something that grew out of a decade of struggle by their teachers union, who has collective bargaining rights, who has a right to strike—all these things that we want.”

One major difference between Houston and Chicago: Public employees in Texas—from teachers like those who bolstered Johnson’s campaign, to firefighters—don’t have a right to strike. When Rob Block joined the Houston firefighters in 2016, cadets made around $29,000 a year. (Coincidentally, those who make that salary today qualify for the region’s new guaranteed income pilot program, because it’s below 200 percent of the federal poverty line.) Block looked into applying for food stamps to make ends meet, and he had friends who took out mortgages on their homes to provide for their families.

Houston firefighters make a fraction of the salaries paid to their counterparts in Dallas or Austin. Voters overwhelmingly approved a 2018 proposition that entitled firefighters to pay parity with police officers (the union says first-year salaries currently hover at $45,000, whereas police first-years can make upward of $74,000)—until the conservative Texas Supreme Court sided with Turner and blocked the measure, sending the parties back to the negotiating table. The decision was a blow to the talks, but the court also affirmed the firefighters union’s right to bargain collectively, leaving the window open for other public worker unions, including teachers.

“Almost everyone in my class took a pay cut” to become a firefighter, Block said. He became a rank-and-file member of the union as soon as he could, and he’s been a Democratic Socialists of America member since 2018. The contract negotiation process with the city left him frustrated, but not entirely surprised. What were their collective bargaining rights if the mayor could simply ignore their demands for years? “You can’t not pay your employees and expect it to go away,” he said.

With many unions already lining up behind Whitmire, University of Houston political scientist Jeronimo Cortina said, it will be important for any left-wing challenger to appeal to remaining progressive constituencies, including Black and Hispanic communities, and, especially, sympathetic “younger, college-age and recent graduate” voters, a group that did not turn out strongly enough to swing New York City’s and Philadelphia’s recent mayoral races. There, crowded fields and divided union support decisively led to victories for center-left candidates.

No challenger from the Houston left materialized in 2019 even though many progressives were disappointed with Turner’s first term. That was not because Houston was infertile ground for progressives: Just a year earlier, Lina Hidalgo, a young Democrat who championed changes to the local bail system and other reforms, rode the 2018 blue wave, and turned the county judge seat blue. But in 2019, a Trump-aligned millionaire sucked all the air out of the room, eventually facing Turner in a runoff, which allowed the incumbent to campaign as a unity candidate.

But with Whitmire the presumed front-runner this year, there is room for an insurgent progressive candidate to emerge. Hidalgo recently endorsed U.S. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee, a longtime liberal who entered the race in April. She’s also garnered support from the Houston Teachers Federation at a time when the region’s public school system is under attack and community support is high. But Jackson Lee is hardly the kind of new, fresh face the left has enjoyed in other cities—her tenure in Congress, which began in 1995, is sprinkled with strange interview gaffes and allegations of staff abuse. (In 2019, Jackson Lee stepped down as the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s board chair amid allegations that she had fired a staffer in retaliation for planning to sue the group over rape allegations.) The remaining candidates seem to lack Whitmire’s and Jackson Lee’s gravitational pull. Indeed, since April, two of the more well-known candidates have already dropped out to seek other electoral seats.

With weeks yet before the August 21 filing deadline, it’s unclear whether anyone in Houston will take up the progressive torch that Maya Wiley in New York or Helen Gym in Philadelphia once carried, but with greater electoral success. It leaves Houston progressives with uncomfortable questions: Who will make up the coalition they hope to build, and how can they overcome the obstacles stacked against them? If, as Block surmised, wins like Brandon Johnson’s require a “decade of struggle,” they must ask when that decade began in their own city—and whether it even has.