In April this year, President Joe Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, gave a speech outlining America’s major economic problems, and the administration’s plan to address them. The industrial base had been hollowed out, he said, and the country had become so unequal that it threatened the foundations of democracy. He identified “one assumption” that had fueled these transformations: the idea “that markets always allocated capital productively and efficiently—no matter what our competitors did, no matter how big our shared challenges grew, and no matter how many guardrails we took down.” Sullivan hastened to add that he was no foe of markets as such. But excessive faith in free markets had left the United States vulnerable to foreign rivals and internal threats.

Sullivan’s speech appeared to signal the end of an era—after decades of influence on both parties, neoliberal ideas seem to be loosening their grip. The Biden administration’s interest in industrial policy—most visible in the Inflation Reduction Act’s effort to accelerate a green energy transition and support domestic manufacturing—represents the center-left’s pull away from Bill Clinton’s declaration that the “era of big government is over.” On the Republican side, too, there has been a shift. Instead of issuing traditional paeans to limited government, many on the right now demand an active and powerful state as the only available weapon against a “globalist” elite, espousing some combination of nationalism and support for favored groups. Both Democrats and Republicans now contain powerful constituencies favoring anti-neoliberal policy.

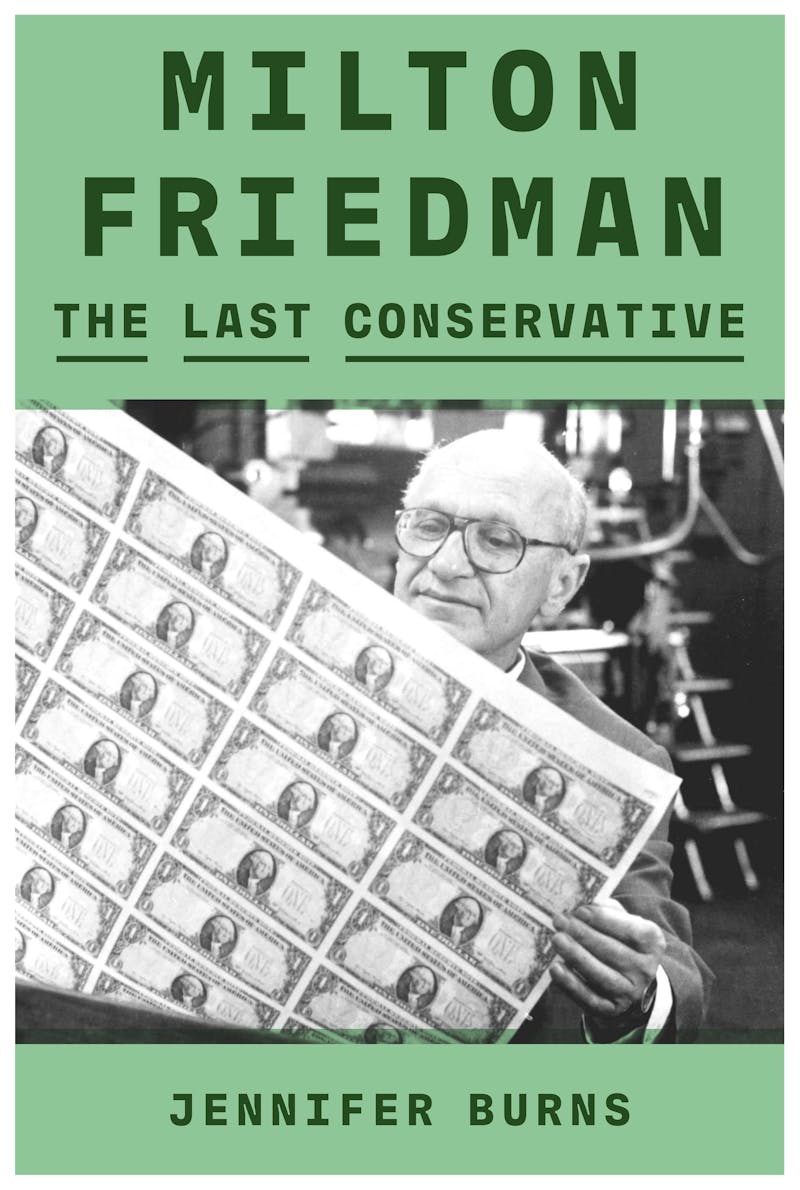

And so Jennifer Burns’s biography of the economist Milton Friedman arrives at a moment when his legacy is increasingly questioned. For no one is more closely linked with neoliberalism than Friedman, who preached the virtues of markets in popular books, on public television, and from his position at the University of Chicago. One of Friedman’s major accomplishments, as Burns describes it, is to have crafted the “basic intellectual consensus about free markets and limited government that powered twentieth-century American conservatism.” For his admirers, Friedman was a farsighted prophet of market economics, a first-rate academic who saw that the world needed more capitalism, not less, to deliver global prosperity. For others, he represents the market fundamentalism that has allowed the wealthy to capture too great a share of the gains of global growth in the neoliberal era, and led to the financial crisis of 2008.

Many books that engage with Friedman are sharply critical. And, more broadly, the last two decades have seen a swell of popular books by left-leaning authors who excavate the history of conservative ideas and engage with them critically, from Rick Perlstein’s Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus to Corey Robin’s The Reactionary Mind. But Burns has opted for a different approach. In this biography, there is enough critique to mark some distance from the subject, but not so much that it would tip into hostility. Burns sees Friedman as an important innovator and an intellectual entrepreneur. If he was “the last conservative,” as her subtitle has it, it is because the American right is moving away from the core principles that he espoused and that helped to define the parameters of conservative thought and identity in the second half of the twentieth century. And if readers do not share Friedman’s way of seeing the world, Burns wants them nonetheless to understand what was appealing about his scholarship and moral philosophy, in its time and place. The book, measured by its own standards, is a success.

But there is a cost, too: Because the book avoids polemic, the reader will not leave with a deep understanding of why Friedman’s influence has faded. There are very good reasons to doubt that his view of the world is the right one for the problems of our time. Burns has written with one kind of fairness in mind. But a more critical look at Friedman’s legacy could have been fair, too. Friedman’s statue casts a long shadow, and a different vantage would have shown something less monumental, but not less true.

Milton Friedman was born in 1912 in Brooklyn to Jewish parents. But the family soon decamped from the frequently left-wing milieu of Jewish New York, and settled in Rahway, New Jersey, where Friedman grew up in modest but basically middle-class conditions. He was bright and hardworking from a young age. The only boy among equally brilliant sisters, it was Milton who had the opportunity to continue his education. From an early interest in mathematics, he earned a scholarship to Rutgers, where he first encountered economics as a potential field of study. There he was introduced to the neoclassical economics of Alfred Marshall, and the 1890 textbook Principles of Economics. “Neoclassical” economics combined broadly laissez-faire ideas with marginal analysis—considering the “marginal” cost or benefit of producing or consuming one more unit of a good or service. Friedman was convinced. Sixty years after its publication, Friedman would still say that Marshall’s book remained the best introduction to the field.

Friedman moved to the University of Chicago in 1932, to study for a master’s degree. It was the institution where he would spend much of his career—teaching there from 1946 until 1977. Many people associated “Chicago economics” with Friedman himself. But it already had a peculiar intellectual culture in the early 1930s. Teachers like Henry Simons and Frank Knight were committed to the view that, broadly, the self-regulating market would do its job best if left alone.

At a time when economists at many schools were convinced that a fundamental change had occurred in economics that required state planning, the approach of “Chicago” economics stood out. The key course was Price Theory, which Friedman would later teach. Price theory at Chicago, Burns writes, was “an architecture of mind”: “Markets and prices … coordinated not just economic activity but the broader society itself.” Well-functioning markets allow producers and consumers to reach an equilibrium, in which supply matches demand. But at Chicago, market logic was extended to the analysis of politics, law, and other domains. Why bother with anti-monopoly law, for example, when the theoretical possibility of competition should keep prices low? Aaron Director, Friedman’s future brother-in-law, called the course a “windstorm” that “swept away the nebulous idealism and Socialist views” he had developed as an undergraduate.

This did not mean that the professors at Chicago were indifferent to the conditions of the Depression. (Paul Samuelson, then a high school student in Hyde Park and later one of the few economists who might be said to have rivaled Friedman’s influence, remembered children and adults coming to the door daily and saying, “We are starving, how about a potato?”) But they preferred solutions that kept the price system intact. Socialism, most thought, was inherently authoritarian, taking away (among other things) the freedom of choice that capitalism offered to the consumer. To fight wartime inflation, they judged higher taxes better than price controls, because the latter would lead to black markets. The government could be called to action in an emergency, but it should not act in a way that could interfere with the basic structures of the market.

Some scholars have written that Friedman was a New Dealer who had a change of heart. But Burns doesn’t think so. It is true that he moved to Columbia for his Ph.D., where the intellectual climate was different. Many Columbia professors were part of the brain trust of the New Deal. Friedman took a job in Washington, too, in the Division of Tax Research at the Treasury Department. But rather than change his worldview, Friedman sought to apply his preferred tools to social problems. After a conversation with the Swedish social democrat Gunnar Myrdal in 1939, for example, Friedman developed an idea for a minimum standard of living that would eventually become the “negative income tax,” in which those earning below some basic level would have their incomes supplemented.

Though never a New Dealer, Friedman did share an ethical universe with economists to his left: He cared about suffering and inequality. He wanted “neoliberalism,” presented at the famous inaugural meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, to have a positive program. He thought negative taxation superior to labor unions, since unions affected the price system (by obtaining wages higher than the market price), and he maintained a place for anti-monopoly actions by the state. The Austrian libertarian Ludwig von Mises stormed out of the meeting, insisting that Friedman and others offering a more pragmatic response to existing conditions were all “socialists.”

Friedman was not, by any reasonable definition of the word, a socialist in 1947, and always wanted the market to be the tool that solved social problems. It was for this reason that he became active in the Republican Party, which he judged more amenable to his views. When, in the run-up to the 1952 election, his friend Fritz Machlup challenged that decision by pointing to the right-wing threat represented by McCarthyism, Friedman countered that the party in power would be better able to contain extremists. But Friedman does seem to have become more conservative over time. By the mid-1950s—following that price theory “architecture of mind”—he had concluded that private monopoly was perhaps preferable to government intervention to break it up. He grew increasingly skeptical of taxation as a method for producing a more equal society. In a series of lectures published in 1956, he listed the following as illegitimate activities of government: rent control, minimum wages, detailed regulation of industries, Social Security programs, licensure provisions, national parks, conscription for military service in peacetime, and legal prohibition of carrying mail for profit. Such views placed him well outside the economic mainstream.

Those lectures became the basis for his book Capitalism and Freedom in 1962, his first real work aimed at a popular audience. It was not an immediate hit, in a striking contrast with Free to Choose, which accompanied a PBS series and was the bestselling nonfiction book of 1980. (Friedman’s wife, Rose, was an important contributor to both volumes, and Burns shows clearly how important she was to his public output.) In the years in between, Friedman’s public profile grew steadily. Support for Chicago economics came from many sources, but most especially from the William Volker Charities Fund, which underwrote Friedman’s travel and lectures. His academic work drew praise, increasing his profile. His 1963 book, A Monetary History of the United States (cowritten with frequent collaborator Anna Jacobson Schwartz), argued that a stable monetary policy was essential for avoiding economic crisis.

Central to Monetary History was the argument that the Federal Reserve had had the power to prevent the Great Depression by expanding the money supply, and failed to do it. This caught the eye of Barry Goldwater on his way to the 1964 Republican nomination, and Friedman provided advice to his campaign. It is here that Burns is most critical of Friedman. For Friedman, like Goldwater, did not support the civil rights movement. Though both men were personally opposed to racial segregation, they saw federal action as infringing on the liberties of the racially prejudiced. Friedman compared laws requiring racial neutrality in hiring to systems of legal discrimination targeting racial or ethnic groups. He instead proposed school vouchers—a market-based system where parents could receive an outlay and then take it to the school of their choice, which did not have to be a public school. Friedman floated vouchers as an alternative to what he understood to be the coercive public monopoly on education, but the idea was soon taken up by segregationists, who flocked to private, whites-only schools as a way of avoiding court-ordered integration. Goldwater won only the Deep South and his home state of Arizona. But Friedman’s star continued to rise; he was given a Newsweek column.

Friedman’s other intellectual bugbear was inflation; at its core, he argued, high inflation was caused by too much currency in circulation, and he warned constantly about its pernicious effects. Other economic schools had more multicausal explanations for inflation, and doubted that high unemployment and high interest rates could coexist. But in the 1970s, those two phenomena occurred together, weakening the prevailing theory but leaving Friedman’s intact. High inflation accompanied by economic stagnation appeared to vindicate him, and his “monetarist” views moved to the mainstream. “The age of John Maynard Keynes gave way to the age of Milton Friedman,” Friedman’s liberal rival J.K. Galbraith admitted at the end of the 1970s.

At the same time, Friedman was also facing some of the sharpest criticism of his career. His trip to Augusto Pinochet’s Chile in 1975 was brief, lasting only six days. But it was seen as a pivotal moment in that country’s transformation into a showcase of “Friedman-style” capitalism, after the military overthrew the socialist President Salvador Allende in 1973. Among Pinochet’s civilian advisers were many economists who had done graduate training at the University of Chicago. Though Friedman himself was not much involved in the program that brought them there, the Chicago ambience had formed them, and Friedman’s visit strengthened their hand.

Writing in The Nation in 1976, Orlando Letelier, Allende’s ambassador to the United States, called Friedman the “intellectual architect” of Chile’s transformation and said, “Repression for the majorities and ‘economic freedom’ for small privileged groups are in Chile two sides of the same coin.” Three weeks later, Letelier was killed by a car bomb planted by Pinochet’s secret police.

Friedman thought the attacks on him for his trip to Chile were deeply unfair. He was heckled at the ceremony awarding him the Nobel Prize in 1976, and dogged by protests for years. It is true that many accusations about him that appeared in print or in person were not accurate, overstating Friedman’s proximity to Pinochet. It is also true that Friedman was advocating for the set of policies he thought would generate well-being. Friedman did not approve of the dictatorship, but he thought that its economic philosophy would eventually undermine its authoritarianism, and he argued against those who thought that his economic vision could only be realized under dictatorial conditions.

But Friedman was more complicit than he wanted to admit. Out of his depth, he adopted much of the far right’s line on Chile. He argued that Allende had “threatened to bring about totalitarian rule of the left.” He also provided a kind of moral authority to the regime with Capitalism and Freedom arguments, asserting in a speech in Chile that “the economic market is a free, more democratic market than the political marketplace.” Over time, Friedman adjusted his message, arguing that there was no trade-off between economic and political freedom. But when he appeared on Free to Choose on PBS stations (and Chilean state television) extolling the virtues of markets, he celebrated the low-tax haven of Hong Kong, a colonial entrepôt whose lack of democracy facilitated its lack of labor rights.

In the 1980s, at the end of his academic career, Friedman was at the peak of his influence. In 1981, Fed Chair Paul Volcker raised interest rates high enough to trigger a recession that lowered inflation, looking like monetarism in action. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher both pointed to Friedman as an influence on their approach to governing, and a broader consensus had formed, across political party lines, about the power of markets and the risks of interfering with them. Union density declined. Privatization of state-owned companies expanded. In 1987, Friedman’s friend Alan Greenspan was appointed to head the Federal Reserve. Free trade, lower taxes, floating currencies, and fiscal discipline increasingly characterized the world economy, and all bore at least some of Friedman’s stamp. Friedman’s “architecture of mind” had gained so much influence, Burns argues, because it provided explanations that helped solve what seemed to be intractable problems.

Another author might have explained Friedman’s influence as the result of the consonance of his ideas with business interests. But in her conclusion, Burns pleads for readers to take Friedman seriously: to understand the appeal even if they do not share it, and not to produce a straw Friedman for easy target practice. She makes her own criticisms; the book is not a defense of Friedman. Friedman didn’t think much about race or gender inequality, she writes, since he saw people as individuals rather than as members of groups. “His concept of freedom was woefully thin,” Burns notes, quite rightly. But, she insists, “Friedman’s ideas have so deeply shaped our current moment that they cannot be tossed away at will.”

And yet: I think it is important not to give Friedman more benefit of the doubt than he deserves. Friedman, who prided himself on his empiricism, and said that economics should be judged on its ability to produce accurate predictions, would have to face the fact that his views on the minimum wage—that raising it would lead to greater unemployment—to give just one example, are not well-supported by empirical study. His argument that the Federal Reserve (and therefore the “government”) caused the Great Depression was a rhetorical sleight of hand. In his scholarship, he laid out a vision of how the Federal Reserve (with benefit of hindsight) might have avoided the Great Depression. In public, this became the claim the government “caused” the Depression. When the Great Recession arrived in 2008, “anti-government” protesters cited Friedman to justify their anger, while Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke cited Friedman to justify the actions he was taking to alleviate the situation.

The aftershocks of 2008 are responsible for much of the reevaluation of Friedman. Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan, testifying before Congress, admitted to encountering a “flaw” in his strategy for managing the market: Rational markets should not have behaved as they did during the housing bubble that led to the crisis of 2008. Bernanke’s actions, following the Friedman recipes, were insufficient to restore the economy to health. The Fed’s program of “quantitative easing,” pumping trillions of dollars into the banking system, helped but was not enough: The post-crisis economy sputtered for years below trend, and people suffered as a result.

In his recent book, Slouching Towards Utopia, the economist J. Bradford DeLong—who comes from a left-neoliberal tradition that is at least respectful toward Friedman—notes that Rose and Milton’s claims to small-government libertarianism in Free to Choose rested on three premises: that macroeconomic crises were caused by governments; that externalities like pollution were relatively small; and that market economies, left alone, would produce a sufficiently egalitarian distribution of income. The Great Recession damaged the first claim. The climate crisis has made a cruel mockery of the second. And many Americans—across the political spectrum—now think that the country’s level of inequality has produced destructive social and political consequences.

Friedman’s idea for making America great again was to return to the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century: “There were few government programs to turn to and nobody expected them. But also, there were few rules and regulations. There were no licenses, no permits, no red tape to restrict them. They found in fact, a free market, and most of them thrived on it.” But it was the Gilded Age that produced the modern labor movement, and the political demands for reform of a world that too many found unsafe, abusive, and insecure. If these developments were a mistake, and we have only fallen in the time since by departing from the principles of market economics, then it is difficult not to conclude (as some libertarians have done) that democracy is indeed the problem. By treating property and contract rights as constitutive of freedom, this kind of thinking offers the rich and privileged a framework from which they can feel aggrieved, even oppressed, by, say, taxation or social spending.

Because of that, it is extremely unlikely that Friedman will be “the last conservative” of Burns’s subtitle. There will be uses for Friedman-style thinking: because of self-interest, and, yes, because of failures of state policies. Friedman partly owed his apparent victory in times of stagflation in the 1970s to circumstances, and his recent downswing to new circumstances. Conditions will of course change again and again: There are many ways to make mistakes in political economy. Friedman’s thought may be at an ebb of influence, but the tides will shift. A book like Burns’s is written to raise the level of debate, not to settle it. But I hope that when the demand for Friedman returns, we will remember not only why it once rose, but also why it fell.