Street protests are an unruly but essential part of democracy. Courts have long held that those who organize them are generally protected by the First Amendment. An unnamed police officer and the most conservative court in the nation want to change all that and, to that end, have filed a lawsuit against a leading figure in the Black Lives Matter movement. In its private conference this week, the Supreme Court will consider whether to take up a case that could rewrite how free speech principles protect nonviolent protesters from legal liability.

The case, Mckesson v. Doe, traces its origins to a police shooting in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 2016. Two officers arrested 37-year-old Alton Sterling after receiving reports of a man at a local food mart who had been waving a handgun around. One of them claimed that, while Sterling was pinned to the ground by both officers, his hand was going for a handgun in his own waistband. One of the officers fatally shot Sterling multiple times. Later reports emerged that Sterling wasn’t the man for whom police had been summoned and that he had been carrying a handgun in self-defense.

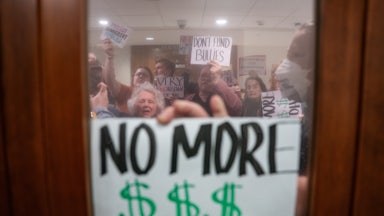

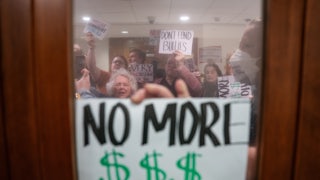

As with many other police shootings that summer, Sterling’s death drew national attention and outrage. Black Lives Matter protesters gathered in the city four days after the shooting to protest what had happened. Among the protesters was DeRay Mckesson, a former educator who became a prominent figure in the movement. He gathered protesters in front of a Baton Rouge police station for a march. The protest, by most accounts, began peacefully but turned hostile toward the officers present. Demonstrators threw water bottles and, eventually, a rock that severely injured a police officer.

Shortly after the protest, that officer filed an anonymous lawsuit against Mckesson and the Black Lives Matter movement. Mckesson played no personal role in the violence—he was arrested that day for obstructing a roadway, but prosecutors declined to pursue charges. But the officer argued that Mckesson was nonetheless liable for his injuries under Louisiana law because Mckesson helped organize the protest and should have known it would turn violent. The officer sought damages for negligence, civil conspiracy, and more.

A federal district court dispensed with most of the complaint fairly easily—Black Lives Matter, for example, is a leaderless movement that lacks a legal personality to sue in court. The civil conspiracy claim was also rejected for insufficient causal evidence. Finally, the judge dismissed the officer’s negligence claims against Mckesson in particular, citing Supreme Court precedent on the free speech implications of such lawsuits.

The Supreme Court has routinely held that participants in nonviolent First Amendment activities, such as boycotts and protests, are constitutionally protected from civil lawsuits for the consequences of those activities. In the 1982 case NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Store, the justices considered a lawsuit brought by white merchants in a Mississippi town who had been boycotted by Black civil rights groups during disputes over racial integration and police violence. The high court ultimately ruled that the First Amendment barred such lawsuits, especially against nonviolent participants.

“The taint of violence colored the conduct of some of the [defendants],” Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the court, referring to sporadic violent acts that had occurred during protests to enforce the boycott. “They, of course, may be held liable for the consequences of their violent deeds. The burden of demonstrating that it colored the entire collective effort, however, is not satisfied by evidence that violence occurred or even that violence contributed to the success of the boycott.”

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ranks as among the most conservative courts in the country, took a different approach from the lower court. Two members of the three-judge panel concluded that Mckesson was in fact liable under Louisiana law for the officer’s injuries. Mckesson appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court, and in 2020, the justices summarily reversed the Fifth Circuit’s ruling. The high court concluded that the panel had erred by deciding complicated questions on Louisiana tort law without certifying the questions to the state Supreme Court first, ordering them to do so.

After the Louisiana Supreme Court weighed in, the panel again ruled in the officer’s favor last June. Two judges on the panel ruled again that Mckesson was liable for his injuries under Louisiana law. They also distinguished the case from the relevant precedent, including Claiborne, by noting that Mckesson allegedly took a much more direct role in the protest.

“To be sure, Doe does not allege that Mckesson directed the unidentified assailant to throw the heavy object, or that he directed the protesters to loot the grocery store and throw water bottles at the assembled police officers,” Judge Jennifer Walker Elrod wrote for the majority. “But the fact that those events occurred under Mckesson’s leadership [supports] the assertion that he organized and directed the protest in such a manner as to create an unreasonable risk that one protester would assault or batter Doe.”

The dissenting vote came from Judge Don Willett, one of the Fifth Circuit’s most conservative judges. Willett is also a frequent critic of the circuit’s approach—and, at times, the Supreme Court’s—to qualified immunity, the judicial doctrine that largely immunizes police officers from civil rights lawsuits. Here too he sought to vindicate constitutional rights in the policing context.

“Officer Doe risked his life to keep his city safe that day—same as every other day he put on the uniform,” Willett wrote. “He deserves justice. Unquestionably, Officer Doe can sue the rock-thrower. But I disagree that he can sue Mckesson as the protest leader. The Constitution that Officer Doe swore to protect itself protects Mckesson’s rights to speak, assemble, associate, and petition.”

Willett rejected the majority’s invocation of “negligence” to overcome Claiborne, arguing that it ran directly counter to the precedent’s framework. Claiborne, he noted, distinguished between violence and nonviolence on whether protest leaders could be sued. Invoking negligence in this case was merely a means by the plaintiff and the court to recategorize Mckesson’s nonviolent acts as violent ones.

“Claiborne assumes that there are categories of conduct in which a protest leader can engage that are ‘unlawful’ under state law but that are still protected under the First Amendment,” Willett explained. “That decision then delineates those categories. The majority opinion rejects the assumption—if not expressly, then by implication, and by a question-begging retreat to legitimate expressive conduct as the dividing line between categories.”

Willett also warned that the majority’s approach ran counter to the broad scope of American history. He noted that the liability theory would have “enfeebled America’s street-blocking civil-rights movement” by “imposing ruinous financial liability against citizens for exercising core First Amendment freedoms.” Willett also observed that Martin Luther King Jr. had sometimes overseen protests, including the one immediately before his assassination in Memphis, that saw outbursts of violent activity.

“Had Dr. King been sued, either by injured police or injured protestors, I cannot fathom that the Constitution he praised as ‘magnificent’—‘a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir’—would countenance his personal liability,” he wrote.

The Supreme Court’s order to vacate the Fifth Circuit’s ruling four years ago was procedural in nature, so it doesn’t formally signal how the court could rule on the merits. It also suggested, however, that at least one of the justices might be in favor of the panel’s approach to protests and the First Amendment. Justice Clarence Thomas indicated in the court’s order that he had dissented from the decision to vacate. Though he did not explain his reasoning in a written opinion, Thomas’s vote suggests he may have approved of how the panel decided the underlying approach to Louisiana law.

A ruling in the anonymous officer’s favor would open up protest organizers and leaders to an entirely new category of liability for organizing large demonstrations. That could impose chilling effects on actions that are otherwise protected by the First Amendment. In the most troubling scenarios, bad actors who oppose a protest’s goals could even anonymously commit violence during a demonstration so that others could sue them for damages. (Nobody ever identified who threw the rock in Mckesson’s case, for example.) With this case, the Supreme Court has an opportunity to reaffirm the fundamental right to protest in American society—or severely weaken it.