I have lived in Bachelor Nation. ABC’s The Bachelor franchise of reality shows—which feature a teeming cast of contestants going on exceedingly strange dates and vying for a marriage proposal from the titular bachelor—debuted at the beginning of the century, and, for its first decade, I largely ignored it. But one season of the show’s gender-swapped spin-off The Bachelorette sideswiped my own real life in a way that was irresistible: A friend’s ex, it turned out, was going to appear as a contestant on the show, one of a couple of dozen perfectly tanned, glamour-muscled dudes living frat-style in the “Bachelor Mansion” high in the hills above Malibu. The very idea of this guy participating in such a strange public ritual was enough to light up the group chats in frenzied anticipation. But he didn’t just appear; he thrived. This person who had once hung out with us, made small talk, and seriously dated someone we knew, was now on television, nimbly navigating a slick and shiny simulacrum of those things. I was hooked.

As we watched, we learned the show’s conventions: the narrative drama of the rose ceremonies, the front-runner edits and the villain edits, the contestants who are there for the “right reasons,” the contestants who “aren’t there to make friends,” the contestants who strangely do seem to be there to make friends, the sliding intimacy scale from having “walls up” around your heart to “letting down those walls,” and the way that “letting down those walls” usually means strategically revealing a traumatic backstory, whether it’s the death of a parent or the loss of a beloved cat.

The Bachelor shows, like most reality TV programs, are highly formalized. Not only does the competition unfold according to the airtight logic of gameplay, but the individual contestants’ behavior follows spoken and unspoken codes of conduct. In one season of The Bachelorette, a contestant—who was something of a front-runner at the time—casually mused that the bachelorette was performing a different version of herself for the camera. He even called her a “TV actress.” He was not launching a critique, simply describing the premise of the situation, and he was taken aback by the bachelorette’s indignation. She immediately dismissed him from the show rather than waiting for the rose ceremony, breaking a rule of the show’s format in order to enforce a fundamental rule of the show’s universe. You don’t break character; you are not a “character.”

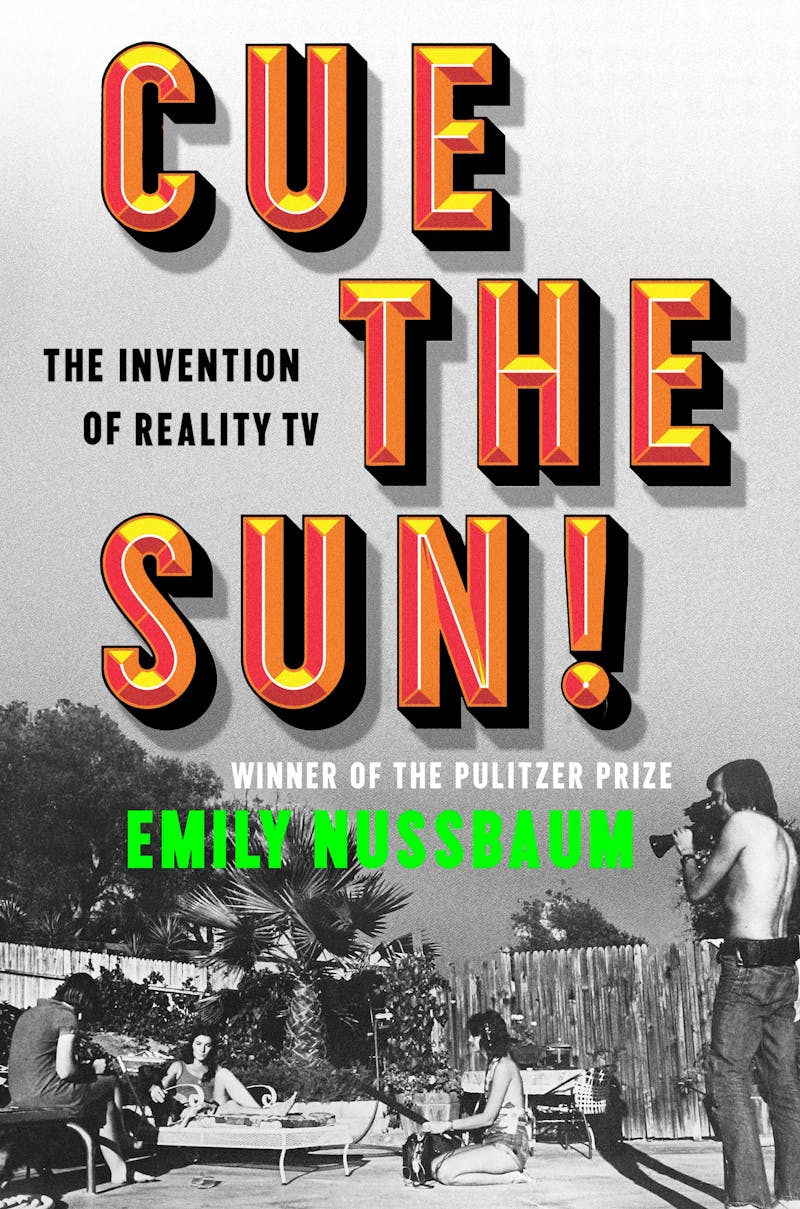

Pulitzer Prize–winning critic and essayist Emily Nussbaum’s new book, Cue the Sun!: The Invention of Reality TV, tells the story of this genre and how its strange codes came, not only to exist, but to be near-universally understood. Tracking the development of reality TV as a genre from the early hidden-camera shows of the 1950s to the sprawling empires of today, the book gives us glimpses into the fraught production of these shows, their divided receptions, and the melancholy biographies of some of the thousands of people who have appeared on these shows only to emerge as strange, fractured mutant versions of themselves, no longer TV characters, but certainly no longer the people they were before.

Nussbaum has spent much of her career arguing for the importance and seriousness of television, even its status as an art form. Reality TV puts her thesis to the test: Sure, The Sopranos is art, but Real Housewives? It’s an old argument, even a tired one, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t still happening. Nussbaum, as always, makes her case for the seriousness of her subject simply by taking it seriously. Attentive not just to the cultural footprint of the reality show but to its ticky-tacky specificity, Cue the Sun! provides a sometimes grim, occasionally gleeful account of the way that television can not just mirror but also create real life.

Cue the Sun! is by no means the first book to examine this topic or to trace the complex ways it’s interwoven into our lives. Lucas Mann’s intimate memoir Captive Audience: On Love and Reality TV (2018) tells the story of his marriage through the reality shows he and his wife have watched together throughout their relationship; media studies scholar Amanda Ann Klein’s 2021 Millennials Killed the Video Star looks at MTV’s transition from music to reality programming, and what the network meant to the generations who watched it religiously; and popular sociologist Danielle J. Lindemann’s 2022 True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us uses the genre as a lens to theorize the social fabric that exists off-screen.

Rather than presenting an “untold story,” Nussbaum focuses on the artistic and ethical dilemmas that shaped these shows, drawing on hundreds of interviews with producers, filmmakers, and on-screen talent. Nussbaum calls reality television “dirty documentary,” or “cinéma vérité filmmaking that has been cut with commercial contaminants, like a street drug, in order to slash the price and intensify the effect.” The story she tells in Cue the Sun! is one of lofty cinematic ambitions compromised by way of hundreds of incremental slippages and brazen betrayals over a period of generations. Alternately craven and credulous, the accumulated acts through which documentary, as a form, came to be “dirtied” in this way amount to a gripping tale of decadence and decay. A rise and a decline all at once.

The genre emerged much earlier than casual viewers might realize, and its early years read like a slow-motion Frankenstein. Nussbaum’s first subject is Allen Funt, who began his career in radio before developing the hit proto-reality series Candid Camera in the late 1940s. Nussbaum paints Funt as both a puckish provocateur and an intellectual theorist of the medium. On the show, unsuspecting people would get chatted up by a mailbox or watch in disbelief as their bowling ball shattered the pins. The stunts were silly, sometimes cringeworthy, but Funt’s patient act of surveillance—catching you “in the act of being yourself,” as he put it—was influential beyond the Nielsen ratings. As Nussbaum points out, David Riesman lauded Funt as “the second most ingenious sociologist in America” in his groundbreaking 1950 study, The Lonely Crowd. Funt was playing with the possibilities of the form, both aware and not of the ramifications his experiments might have down the line.

Then, there’s An American Family, the infamous 1973 PBS documentary series that first truly revealed the sticky ethics of following regular people around with a camera for the sake of mass entertainment. The show—which tracked the everyday lives of a California family in the midst of a divorce—was a controversial hit, but its production and reception were defined by an internal schism that would characterize the genre itself. On one side were Alan and Susan Raymond, the husband-and-wife filmmaking duo who shot most of the footage for the series. They were committed to the documentary principles of cinema verité, the idea that “if you recorded with your camera and microphone for long enough, with enough patience, eventually the truth would emerge.” This approach, which the Raymonds regarded as “almost a religion,” is at the core of why anybody has ever responded to reality TV, the idea that the camera might find something otherwise hidden, precious. But the Raymonds found themselves at odds with Craig Gilbert, the show’s mastermind and producer, who compromised the principles of verité by involving himself in the lives of the family, by adding narration to the final cut, and editing the footage in suggestive and even salacious ways—and who thereby helped establish the norms so familiar to us now.

This tension reappeared surprisingly often as the giant reality franchises of the 1990s and early aughts—The Real World, Survivor, and Big Brother—emerged. In one telling moment early in the filming of The Real World, for instance, a producer plants an embarrassing object in the loft’s kitchen—an art book that contains a nude photo of Eric Nies, one of the cast members—in order to provoke filmable reactions from the other cast members. When Nies discovers what’s happened, he reflexively looks straight into the camera, to the producers he knows are watching. Nies breaks the on-screen illusion, but only because the producers looking back had broken a much more fundamental rule, by messing with “reality” itself.

It’s a revealing anecdote—about the fine line between exploitation and performance, about the emergent ethics of the genre, about the psychologically complex (if deliberately undertheorized) collaboration between screen talent and producers that undergirds all of these shows. But it also marked the moment when something irrevocably changed—when the violation of verité became standard practice, rather than an aberration. One producer opposed the planting of the book because, in Nussbaum’s words, it “would taint the format’s purity.” Later in the same show, a director insisted that cast members kiss at the end of a blind date—a moment that another of the show’s directors described as “the original sin of reality television.”

Purity. Of all the words we might use to describe this genre of entertainment, purity is certainly not one of them. But, in Nussbaum’s telling, for decades, reality TV producers and stars held onto the lofty ideal that what they were doing held the possibility of a sort of pure or unmediated access to the human condition. Nearly all of the foundational decisions in this mode’s history are also violations or betrayals. “Dirty documentary” is powerful, not only because of its mass appeal over the course of decades, but because somewhere out there in an alternate timeline, it might have been something better. The real tragedy is that any of these idealistic, even brilliant people ever believed that.

Perhaps because Nussbaum writes with a keen sense of the genre’s manipulations, she often credits the shows’ producers with making the kinds of choices an auteur makes, and she watches them with the kind of attention usually reserved for more noble genres. Cue the Sun! breaks down the visual language of each different show, stopping frequently to describe the particular dynamics of individual scenes, moments monumental and passing. There’s Pat Loud—of An American Family—smoking a cigarette in loose white pants on the sofa as she negotiates her divorce; the chaotic scramble of producer Mark Burnett initially dividing Survivor contestants into “tribes” after their arrival in Borneo; a port authority worker quietly working through his internalized homophobia with Kyan Douglas on an early episode of Queer Eye. Nussbaum sees these human moments as screen moments and describes them with the same care she might otherwise apply to a prestige drama series.

Likewise, she underlines the importance of logistics in these shows. Reality TV is an art form and an industry, a craft and a business. Its history, Nussbaum suggests, is actually a history of specific evolutions in form, from editing to production design. Where is the camera? Where are its subjects? How do the editors draw them together or slice them to shreds? These formal questions are the real questions at the heart of the genre. Especially as the book moves into the genre’s decadent aughts period, she describes on-screen moments alongside the often grotesque behind-the-scenes machinations that produced them—the ethical violations of the genre cementing themselves in its formal architecture.

We read about the way Big Brother producers manipulated the design and arrangement of furniture on the set in order to pit contestants against each other. We track the development of the “Frankenbite,” a technique used to spackle snippets of speech together to form misleading sound bites. There’s even the moment when Project Runway contestant Jay McCarroll admits that “his own memories had long since been displaced by the edited version of the show.” This genre that once imagined it could use the camera to capture the truth of existence had managed to replace the truth of existence with the camera’s effects.

I left Bachelor Nation for a while as it predictably fell to accusations of racism and sexism on set. As Nussbaum chronicles in the final section of her book, reality TV was an industry made for, and increasingly by, scammers and bad guys. Producers like The Bachelor’s Mike Fleiss and stars like The Apprentice’s Donald Trump are poster boys of the loss of purity once bemoaned by those early Real World producers. And, as much fun as it was to watch all those cringeworthy hot-air balloon dates, at a certain point guilt overwhelms pleasure. What Nussbaum calls the “erotic terrarium” of the Bachelor Mansion starts to stink.

But something last fall brought me back: The Golden Bachelor. The concept of The Golden Bachelor was that it was the same show we’ve come to love and loathe, but, instead of 28-year-old personal trainers, the contestants were sixty- and seventysomething retirees. It was an intriguing switch. The Golden Bachelor not only drew me back in; it shocked me.

For the 14 or so years that I’ve been watch-ing these shows, I’ve been seeing contestants who have also been watching the show itself and learning from it. Nearly everyone who appears on the countless reality series that have grown up in the past 30 years arrives at taping having already studied the role and the way others have played it before them. Even the most starry-eyed romantics show up with a plan. That’s as true on The Bachelor as it is on The Amazing Race or Real Housewives, and it can give the enterprise a stagy quality: Though the show is full of tears and tension, nobody really gets hurt, and nobody’s really there for “the right reasons,” unless those reasons include securing a contract to do sponsored-content posts for skin care brands on Instagram.

But this was not the case on The Golden Bachelor. The cast of characters was the first set of older contestants on the hit show and came in without age-appropriate models to imitate. Some interactions were sweet, some sour, some deeply melancholy, but none formulaic. It felt both refreshing and dangerous to watch. If there are more editions of this particular spin-off, we’ll start to see better-versed contestants, people who have identified the elements of a winning performance. But the first season, in which a houseful of elderly women bond and bicker and speak frankly about loss and mortality and hope, appeared to capture something real, or at least something hidden in plain sight and that television had managed to uncover.

Like Cue the Sun!, The Golden Bachelor revealed something true about both reality TV and the world it mediates. Reality television didn’t put our reality on the screen, it splintered that reality. Shows from Candid Camera to The Golden Bachelor serve up a universe that is neither the one we live in nor one entirely fabricated. The “reality” of reality TV is a secret third type of reality, a place where we perform a shadow play of our lives for others, a place where we cling to flimsy distinctions like viewer and viewed, a place tarred by exploitation but enlivened by optimism, or something like it. We are in it, we are of it, whether we watch or not.