One evening in December 1850, an escaped slave named John Andrew Jackson arrived at a handsome, white clapboard house in Brunswick, Maine, cold and desperate for somewhere to stay. He was fleeing north to Canada, striving to evade the slave-catchers who had just been empowered by a new law, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, to capture runaways even in free states like Maine. Upon arriving at the Brunswick house, Jackson encountered its mistress, a young housewife (and burgeoning writer) named Harriet Beecher Stowe. She considered whether to grant him refuge. Her husband was hundreds of miles from home. Before the Fugitive Slave Act had passed, Stowe later reflected in a letter, she might have “tried to send him somewhere else.” But these were desperate times. She allowed Jackson to sleep under her roof, giving him a bed in “our waste room.” Jackson, a gifted raconteur, entertained her children with stories and songs.

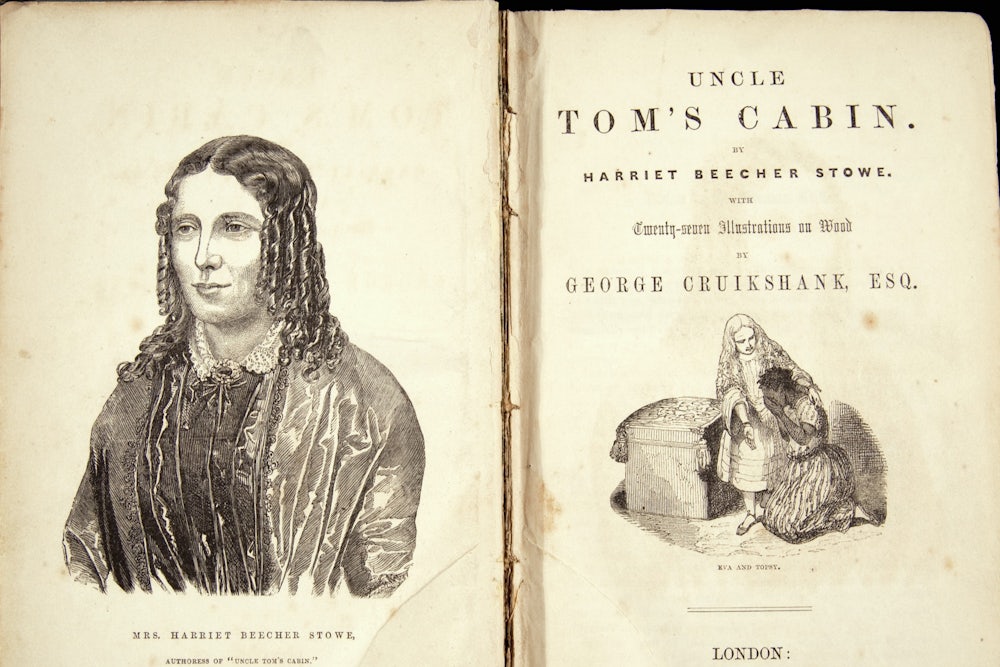

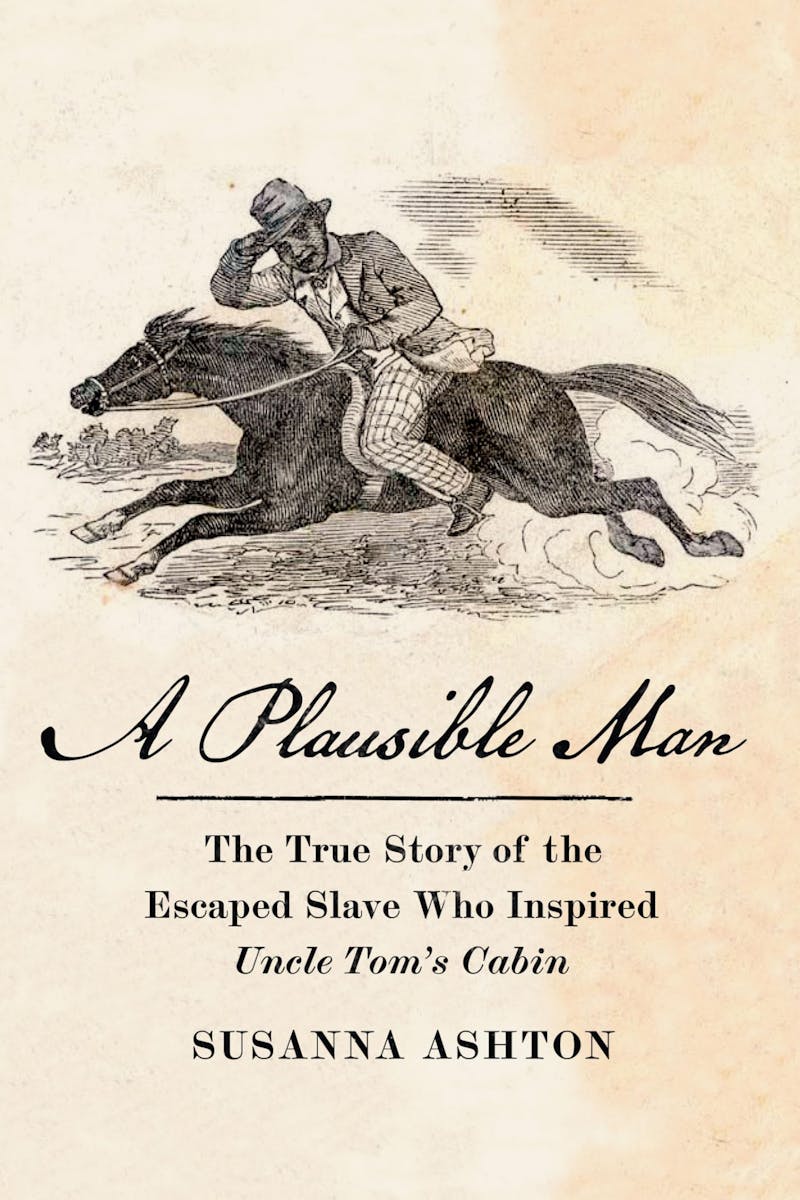

Jackson stayed with Stowe for just a single night, but—writes the historian Susanna Ashton—it was “an encounter that, quite possibly, changed the world.” As Ashton argues in her intriguing new book, A Plausible Man: The True Story of the Escaped Slave Who Inspired Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe drew on this fleeting interaction when, just seven weeks later, she began to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The novel, which tells the story of a long-suffering enslaved man, sold at least 300,000 copies in its first year and helped to inflame the passions of a nation hurtling toward war.

Yet if Stowe’s protagonist was so forbearing that his name has become an epithet, Jackson is a far more compelling figure. An epic, thousand-mile escape from slavery to freedom was only the first act in a life that spanned the pulpit, the jailhouse, and a daring attempt to buy his former owners’ land. Jackson told his own life story in an 1862 memoir that serves as one of Ashton’s main sources. She came upon the memoir while “hunting down rare or out-of-print slave narratives” and was so entranced by Jackson’s “big personality” that she decided to dig further. The resulting book, though billed as biography or literary history, is more properly read as somewhere between a detective story and a caper. In searching for John Andrew Jackson, Ashton has depicted with nuance and restraint a life story that complicates the kind of mawkish or tidy assumptions about enslaved people contained in many works, perhaps most famously Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Her main character’s elusiveness is the story’s most remarkable feature.

“I was born in South Carolina,” begins John Andrew Jackson’s memoir, published a decade after Uncle Tom’s Cabin. His parents, Betty and the unusually named Doctor Clavern, were slaves on the Sumter County plantation of Robert English. John Andrew came into the world in 1825, one of the more than 50 slaves owned by English, most of whom were forced to pick short-staple cotton beneath a burning sun. For reasons still obscure, he was apparently also known to his enslavers as “Jackson.”

English was a striver, a locally powerful but widely disliked property owner; his wife, Elizabeth, and four daughters were memorably abusive, apparently delighting in whipping their slaves. According to Jackson’s memoir, the youngest English daughter, Martha, once ordered Jackson’s sister to be whipped 100 times for refusing to stop praying; the sister died as a result of the beating. Jackson himself was forced to endure “many whippings,” he would write.

Sometime before 1840, Jackson began a relationship with another enslaved woman, Louisa, with whom he soon had a daughter, Jinny. English was irate, as Louisa belonged to a neighboring enslaver, meaning Jinny and any other children Jackson and Louisa would have would be the property of Louisa’s owner. English beat Jackson every time he visited Louisa—“at least every week,” Jackson later wrote. “I shall carry these scars to my grave.” To make matters worse, Louisa’s owner soon moved to Georgia, sundering Jackson’s family.

Jackson apparently sought solace in prayer—and in resistance. In 1846, he somehow acquired a pony and rode it to a religious meeting without permission, an act of defiance so unforgettably bold that Irving Lowery, an enslaved man who lived nearby, wrote about it more than 50 years later in his own memoir. Elizabeth English ordered her overseer to give Jackson a hundred lashes—“a terrifying punishment … not far off from being a death sentence,” Ashton wrote—but he managed to flee into the nearby trees. Realizing he was “stuck in the swampy woods without recourse, supplies, or a feasible plan for sustainable escape,” Jackson returned the next day, but soon thereafter, on Christmas Day, he retrieved his pony and escaped for good. Desperate to recapture their lost property, the English family ran an advertisement offering a reward for his apprehension. Noting his cleverness, the advertisement warned white readers that Jackson “speaks plausibly.”

Armed with little more than his plausible tongue, Jackson managed to charm a procession of acquaintances into helping him escape nearly 900 miles to Massachusetts. He quickly set about trying to raise enough money to purchase Louisa and Jinny’s freedom, making valuable contacts with nearby abolitionist activists. Soon, he was traveling around Massachusetts, telling his story and soliciting donations. It was the beginning of a life of storytelling, reinvention, and tireless fundraising.

Not long thereafter, in 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, forcing Jackson to flee once again. It was on his trip north that he spent a single night at the home of Harriet Beecher Stowe. From her waste room (essentially a storage closet), Jackson moved on to other towns in Maine, apparently passing the freezing winter of 1850–51 in Portland. Once again, his skill at connecting with nearby activists ensured his safety—and ultimately his passage into Canada.

Ashton recounts the remainder of Jackson’s life with aplomb, ably covering his years of lecturing in Canada and then in England, his itinerant preaching, his acquisition of literacy, his decision to write a memoir, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina, and his remarriage, to Julia Watson, a runaway slave from North Carolina. The details of Watson’s life are few, but it is evident she accompanied her husband to England and sometimes lectured onstage alongside him, making her “possibly the first African American woman to speak in the British Isles about her enslaved experiences.”

Throughout the 1860s, Jackson attracted fans and donations yet consistently alienated allies, including financial benefactors. He had “spent his life carefully constructing a persona of resilient bravado,” Ashton writes carefully; he “wasn’t a man to back down.” Shortly after the end of the Civil War, Jackson and Watson returned to the United States, where he found work with the Freedmen’s Bureau. He set about trying to buy up his former owners’ land and turn it into a community for freed slaves—or for his own family. It was just one among many utopian visions for the postwar South, and—like most of these visions—it faded amid fierce white supremacist resistance.

Jackson continued to lecture and fundraise but repeatedly encountered legal jeopardy; in North Carolina, authorities brought charges of financial swindling against him (Ashton calls them “trumped-up”) and he was sentenced to five years of hard labor. The aging man served little of it, briefly escaping from prison and then managing to secure a swift release after journalistic allies turned his conviction into an international scandal.

Toward the end of his life, Jackson did attain small plots of South Carolina soil, including property that had “almost certainly” been owned by “English family relatives.” But his dreams for this land amounted to little. It was “not unlikely” Ashton writes, again with tact, that he was “pilfering or profiting from goods that had been donated.… He had always been a bit of a hustler, a survivor.”

In reconstructing a life that included so many wild twists and turns, drawing on sources drenched alternately in their recordkeepers’ racism and the protagonist’s self-mythologization, Ashton has accomplished something remarkable, a feat of historical excavation. She unearths myriad newspaper articles, court records, and letters, though she also reflects on “what can and cannot be recorded.” The result of her digging is a nuanced depiction of Jackson, a man possessed of almost unfathomable resilience and also chutzpah, a combination that led to both iconoclasm and apparently fraud. Understandably, her sources do not allow Ashton to paint her other characters as convincingly, occasionally resulting in a flattening sentimentality. Jackson’s mother, Betty, “must have been someone special. Someone fearless”; his wife, Julia Watson, “must have been remarkable.” Must they? Ashton is on firmer ground in refusing to make such demands of Jackson.

The most newsworthy of Ashton’s conclusions are her claims about Jackson’s influence on Harriet Beecher Stowe. For it is these claims—featured centrally on A Plausible Man’s book jacket and in its marketing material—that go beyond the biographical, instead seeking to reframe one of the most famous works of American literature. While Ashton insists that the more “significant story” inspired by Jackson was “his own,” no doubt many readers will arrive at this book trying to learn more about the origins of another.

From nearly the first moment it appeared in print, Uncle Tom’s Cabin inspired readers to try to discover Stowe’s inspirations. Within a year, Stowe had published The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an assemblage of the press reports, slave narratives, and other sources from which she claimed to have either drawn or found subsequent “confirmation.” For the character of Tom, Stowe cited the life of Josiah Henson, a legendary abolitionist and escaped slave who eagerly claimed credit for inspiring the novel, as well as the husband of her former servant, who was “such a Christian,” Stowe later wrote, that he refused to escape from bondage. The scholar David S. Reynolds, author of perhaps the definitive cultural history of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, adds a number of other inspirations, including the former slaves Lewis Clarke and Thomas Magruder.

Other authors have been less careful in locating the novel’s sources. In the 1940s, Stowe’s biographer, Forrest Wilson, claimed to have come across “an ex-slave woman” named Margaret Garner who “escaped over the frozen Ohio River and thought she inspired” Stowe’s character of Eliza, perhaps the novel’s most memorable, who likewise fled to freedom across the ice floes of the Ohio. Yet Wilson’s story was untrue; Garner did not escape slavery until 1856, four years after the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Garner herself apparently died in 1858. If anything, the novel shaped public perceptions of Garner, who became infamous for having killed her infant daughter (and trying to kill her other children) rather than allow them to be returned to slavery.

Ashton, for her part, is generally careful in assigning credit to John Andrew Jackson, who—she is clear—was not a source for Tom himself. Rather, she argues that his passing presence in Stowe’s house was what inspired the writer to put pen to paper. Jackson had made slavery real—and urgent—to the Maine housewife.

Stowe was not the first resident of Brunswick to whom Jackson had turned for refuge; instead, he had first traveled to the home of an abolitionist mathematics professor, who directed Jackson to go to the home of his neighbor, the Reverend Thomas Upham, who in turn sent him on to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s house, a block away. Stowe, a harried young mother with a houseful of children and servants, was at home without her husband, who was finishing up his job at a Cincinnati seminary. She had recently debated the Fugitive Slave Act with the Reverend Upham over tea; when she asked him whether “he would obey the law supposing a fugitive came to him,” he had “hemmed & hawed,” she recalled in a letter to her sister. Now, confronted with an actual fugitive slave, Upham had “overcome his fussy civic scruples,” Ashton noted, giving Jackson a dollar and directing him to Stowe’s for sanctuary.

Safe at Stowe’s house, Jackson delighted her children with stories and songs, leading his hostess to write to her sister of the “mysterious power of pleasing children” that “these negroes posses[s].” Yet her casual racism aside, Stowe was deeply moved by Jackson’s brief stay. According to his memoir, he told her his life’s story, to which she listened “with great interest.” At one point, he took off his shirt so she could inspect the scars he bore from years of whippings. Stowe neglected to mention this particular interaction to her sister; it was, in fact, a striking breach of decorum for the personally conservative wife of an absent theologian. It was, Ashton writes, “an intimate and harrowing moment.”

Just weeks later, Stowe began to write her novel. The timing is crucial to Ashton’s argument. She observes Jackson’s influence in two ways. First, more narrowly, Ashton notes striking parallels between Stowe’s description of her own conversation with the Reverend Upham and a conversation in the novel between Senator Bird of Ohio and his wife, in which the man responds condescendingly to his wife’s shock at the cruelty of the Fugitive Slave Act. Just moments later, the character Eliza—the enslaved woman who had escaped over the frozen Ohio River—shows up at the senator’s door, freezing and desperate. Like the Reverend Upham confronted with a fleeing Jackson, Senator Bird instantly forgets his hesitancy and concocts a plan to secure her safe passage north. “Your heart is better than your head,” Mrs. Bird tells her husband.

More broadly, Ashton argues that Jackson had made slavery unignorable to Stowe. He had brought its horrors directly into her home. He had turned the abstract into the concrete. The pivotal nature of this interaction, Ashton continues, was its “domestic” character. Jackson was not Stowe’s servant, nor was he a lecturer whose speech she happened to hear; he was Stowe’s guest, a man who had sung with her children, who had bared his back for her to see.

“So, if Jackson had taught Stowe about slavery, why didn’t she mention him again in public?” Ashton asks rhetorically. Not once did Stowe include him among her inspirations; he is absent from The Key. Ashton posits several explanations: Stowe may not have recalled, or even known, Jackson’s name; his visit with her had been illegal; perhaps most importantly, he had stayed under her roof—and even removed his shirt—while her husband was far away, rendering the interaction “unseemly according to the mores of Victorian America.”

Jackson, for his part, was “surprisingly restrained” in asserting his connection to Stowe and her novel. In fact, he may not have immediately realized the connection upon the novel’s publication in 1852. Four years later, though, he wrote to Stowe, asking her to write him a testimonial, verifying his story and endorsing his character. Stowe complied; frustratingly, her letter has since been lost, though others at the time described it as a notably “strong” endorsement. Jackson would subsequently mention his connection with Stowe onstage, but he was careful not to overstate their relationship. At no point does it appear he claimed to have been a model for the novel’s titular character (though at least one journalist wrote that Jackson “remind[s] one strongly of Uncle Tom”). In the century following Jackson’s death, his association with Stowe—and, indeed, his remarkable life story—fell into obscurity.

Ashton deserves credit for bringing attention not only to Jackson’s apparent influence on Stowe but also to his dazzling biography. Yet a question remains, unaddressed by Ashton: Why do we care what fragments of truth inspired Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Beyond mere trivia, what do we learn by tracking down the inspirations for famous works of literature?

It’s a question with implications far beyond A Plausible Man. Indeed, in recent years there has been something a boomlet of nonfiction books purporting to uncover the origins of iconic characters. In 2018, in Atticus Finch: The Biography, the historian Joseph Crespino identified A.C. Lee, Harper Lee’s father, as the model for his daughter’s most famous character. That same year, the crime writer Sarah Weinman released The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel that Scandalized the World, likewise identifying the “real-life case” that inspired Vladimir Nabokov’s most famous work. Other writers have claimed to have uncovered the true stories behind The Great Gatsby, Dracula, and the supposedly mythic folk hero John Henry.

The fame of these characters and novels is invariably cited as justification for plumbing their origins. Atticus Finch, Crespino writes in his book’s introduction, has become “one of the most beloved characters in all of American literature … an essential symbol of empathy and tolerance in American public life.” The “immortality and cultural omnipresence” of Dracula, the critic David J. Skal adds, is what necessitates a deep dive into the character’s origins (which lie, Skal argues, fairly convincingly, in Bram Stoker’s sexual identity). Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Ashton tells us, “helped inspire the most consequential social revolution in the history of the Western world: the overthrow of modern slavery.”

Sometimes, though, a slippage occurs, with writers crediting the historical inspirations themselves for shaping American fiction or history. Sally Horner’s “uniquely American” abduction and murder, Weinman claims, “reverberated through the culture, and irrevocably changed the course of twentieth-century literature.” Likewise, Ashton posits that Jackson’s single night under Stowe’s roof may have “changed the world.”

Yet what was truly world-changing, this meeting or Stowe metabolizing it into prose? Was it Horner who altered the course of literary history, or was it Nabokov? Writing in The New Yorker, the critic Katy Waldman has called Weinman’s approach “fundamentally anti-fiction.” To Weinman, Nabokov “strip-mined” Horner’s story; to Waldman, he managed to transform “cruelty” into “something beautiful.”

Novelists too have pushed back on what they perceive to be an excessive focus on locating the true stories behind the fiction. Toni Morrison, for instance, was always upfront about the fact that Margaret Garner—the escaped slave, mentioned above, who killed her infant daughter as pursuers closed in—inspired Sethe in the novel Beloved. But Morrison insisted to the press that she pointedly did no research: “I refused to find out anything else about Margaret Garner. I really wanted to invent her life.”

There is, of course, a danger to such invention. Stowe, for one, plumbed the depths of her own compassion to give voice to the most oppressed members of her society; in so doing, she betrayed the profound limitations of her perspective and imagination, lapsing frequently into ventriloquism, romanticism, and racist condescension. “She was not so much a novelist,” James Baldwin famously wrote of Stowe, “as an impassioned pamphleteer.”

In an essay titled “Who Speaks for Margaret Garner?” the historian Mark Reinhardt considered what might constitute “a responsible telling” of the life of another enslaved subject. He concluded that such a telling would need “to be silent about many things. Her silences can be discussed; it is important to seek their sources, trace their contours, take their measure. But doing so requires a refusal to fill them in.” (Morrison, he notes, spent five pages setting the scene for the death of Sethe’s daughter but ultimately gave readers “no glimpse of the precise moment of the killing.”) The scholar Cynthia Gunther Kodat has added that a “sensitive portrayal of Margaret Garner demands some sort of critical reckoning with past efforts to make her story work, efforts that, in their determination to make her serve some higher end, failed to see Margaret Garner herself as a human being.”

Which returns us to Ashton’s project—and its core contribution. A Plausible Man is persuasive in demonstrating Jackson’s influence on Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but more notable is its success in a mission at which Stowe failed: recounting the life of an obscure man in all of his messiness. Ashton refuses to reduce her subject to a mere inspiration for a writer. Instead, she revels in the gulf between history and its portrayal, the distance between the evidence in the archive and any neat takeaways. This, in the end, is the greatest value of works seeking to locate the origins of famous works of fiction: not to debunk the originality of art, but instead to complicate our understandings of reality.