Men, and particularly white men, have long been a key constituency for former President Donald Trump. His 2016 victory was owed in part to his strength among white and male voters, and his loss in 2020 involved a decrease in their support.

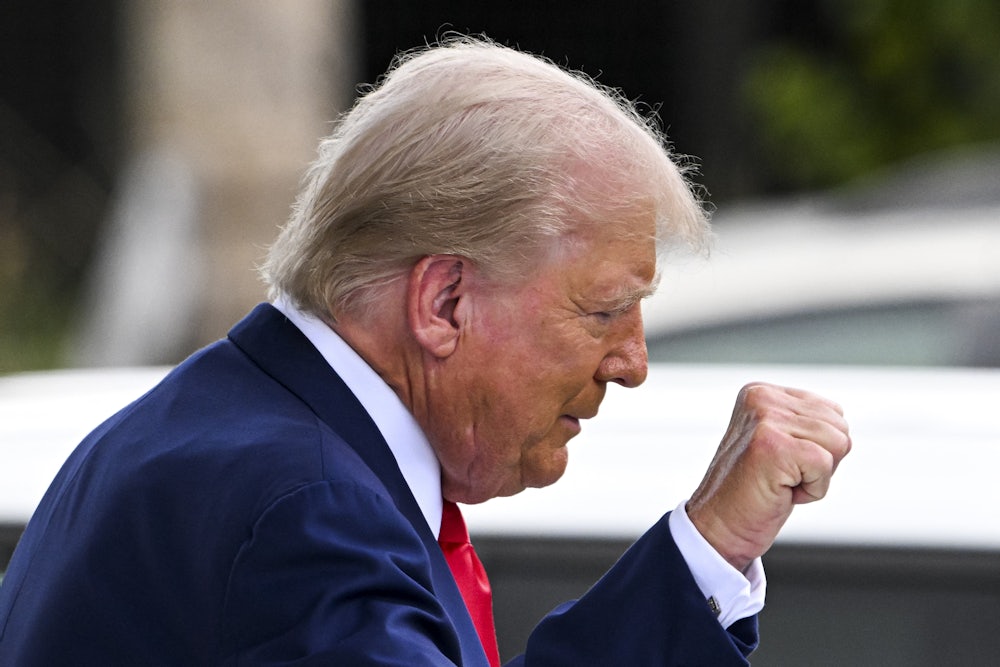

With Vice President Kamala Harris now at the top of the Democratic ticket, Trump’s particular brand of tough-guy masculinity may play an important role in his appeals to male voters, and especially young men, who have trended Republican in recent years.

In recent weeks, Trump has participated in interviews with influencer Adin Ross and YouTuber Logan Paul, who primarily cater to young men, indicating his interest in reaching those voters. He also chatted with billionaire Elon Musk last week. A recent poll by the Young Men’s Research Institute found that 68 percent of American young men surveyed “like” Musk and 52 percent said they had used X—the social media site owned by Musk, formerly known as Twitter—in the past week.

Trump’s running mate, Ohio Senator J.D. Vance, has also appeared on the popular Full Send podcast, hosted by a crew of internet personalities known as the Nelk Boys. They debuted a $20 million campaign to register and motivate young voters in battleground states, The Wall Street Journal reported, partnering with sports figures such as athletes from the Ultimate Fighting Championship—a sport that has become entwined with Trump support.

“They’re trying to meet young men where many of them are,” said Melissa Deckman, CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute and the author of a forthcoming book on Gen Z politics. “There’s a deliberate strategy by the Trump campaign to reach out to, especially, disaffected young men. A lot of those men care a lot about the economy, but I think they’re also drawn to the perception that Trump is very strong.”

Young men’s alienation can be partially attributed to economic struggles and to a sense that opportunity has been taken from them—an opinion promoted by podcasters and influencers in the “manosphere,” a network of internet communities preoccupied with men’s rights and maintaining traditional gender roles. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that young men were less likely than young women to achieve key milestones like financial independence and a full-time job by the age of 25.

Recent polling has also shown that there is a growing gender gap among young men and women in partisan support: While voters under 30 have long supported Democrats, males are increasingly trending toward Republicans. Daniel Cox, the director of the Survey Center on American Life and a senior fellow in polling and public opinion at the American Enterprise Institute, said that young men aren’t necessarily adopting more Republican views—they may just connect more with what GOP politicians are saying about the economy and the societal roles of men.

“There’s just significant evidence of political apathy,” said Cox. “There’s an overall sense of confusion and dislocation and a lack of clear direction for a lot of young men about where they fit in, what it even means to be a man, how they navigate this changing cultural landscape.”

Another recent Survey Center on American Life poll found that only 43 percent of Gen Z men think of themselves as “feminist,” compared to 61 percent of women; 45 percent of young men also said they have faced discrimination because of their gender.

Research by the American Institute for Boys and Men indicates that young men are not wholly turning away from gender equality, and largely support women’s participation in the workforce. Still, if some young men think of women’s advancement as a zero-sum game—a position promoted by members of the manosphere—they may be more inclined to listen to political candidates who argue in favor of traditional gender roles.

Democratic Senator Chris Murphy argued that Democrats had ceded the conversation on masculinity to Republicans. “We certainly should believe that masculinity can exist side by side with feminism, but we’ve got to acquire a language to talk to boys and men about the future of maleness, and right now we don’t have it,” Murphy said. “I do not think the majority of men believe that women should be removed from the workplace, but they notice when Democrats aren’t talking about addressing some of the real crises that exist in male identity today.”

By contrast, Trump and Republicans are able to offer an alternative to men and boys, one that is not focused on the negative side effects of “toxic masculinity” but what men can and should be able to accomplish.

“Trump’s vision, to the extent that he has one, is not saying that men are a problem, but there’s absolutely a place for strong, willful men to play a role here. And you don’t have to apologize for being a man,” Cox said. “That’s quite obviously attractive for a lot of young men.”

This is also a familiar tactic for Trump, who frequently wedges identity into his critiques of the Democratic Party. “Younger voters have trended Democrat for some time now, so it’s very much in Trump’s playbook to try to break that demographic in half to appeal to younger men, to try to tell them that they are being treated poorly—in the same way that, when he talks about race, he often pits Latinos against Blacks, or does other things to try to split up groups that might be seen as being Democratic,” said Robert Boatright, political science professor at Clark University and co-author of a book on misogyny in the 2016 presidential election.

When President Joe Biden was still seeking reelection, Trump appeared to make significant inroads with young men. The annual Harvard Youth Poll, published in April, found that young men supported Biden over Trump by six percentage points, a dramatic reduction of 20 percentage points from his lead against Trump in 2020. The poll also found that young men were far less likely to identify as Democrats in 2024 than they were in 2020.

However, Harris may do better at the top of the ticket than Biden. The polls that showed Trump gaining with young voters may be an “artifact” of a race that no longer exists, Boatright argued. “Much of the polling this year suggested that Trump was going to perform better among a lot of groups—younger voters, Black voters, and so on—than any Republican nominee in decades,” he said. But if Harris does well with young men voters, that indicates that the gender gap may be, if not overstated, then less important in the presidential race.

Recent polling has Harris making up significant ground with young voters in general, helping her gain against Trump in key states. That trend may extend to young men, as well: A late July poll by the Young Men Research Initiative found Harris underwater with young men who were not registered to vote but up 17 percentage points against Trump among young male registered voters. A Pew poll published last week found that young men voters aged 18 through 29 supported Harris over Trump, 55 percent to 31 percent, with 14 percent support for Robert F. Kennedy.

But these findings are not universal—an August poll of young voters by the Democratic group Won’t PAC Down found that while Harris leads Trump among all registered young voters, she lags among young men in the eight battleground states.

Biden appeared to be a weak candidate against Trump, Deckman said, which discouraged support among young men who valued toughness. Harris’s background as a prosecutor may convince voters, including men, that she is as much of a fighter as Trump.

“Suddenly, I think those attributes have the ability to make her appear just as strong as Donald Trump, and so might neutralize Trump’s attempts to court young men voters who really care about having a strong candidate,” Deckman said.

Harris may also be absorbing some of the lessons from Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. In that election, Clinton emphasized her historic nomination as the first woman at the top of a presidential ticket. In contrast, while Harris’s nomination has energized some women voters and people of color, she has not made her racial or gender identity a critical part of her campaign. This may be strategic: Polling by the Young Men’s Research Institute also found that male voters under 30 supported a generic female candidate who campaigned on economic messages over Trump by a larger margin than a generic female candidate who highlighted the importance of being the first female president.

The different experiences of young men and women—the fundamental ways in which they understand the world—may also factor into their support for Harris, or lack thereof. Cox cited a recent focus group he had conducted, in which he interviewed young people about Harris’s candidacy. For young women, Harris’s gender was not the most salient factor in their support for her; however, the young men interviewed believe that women are only supporting Harris because she is also a woman.

“I think it does suggest there’s just some degree of dissonance, or a gap between young women and men, where they’re not understanding where the other side is coming from,” Cox said.

There is also the possibility that Trump’s overtures to disaffected young men may have unintended effects, as they could motivate populations that are more likely to turn out in November.

“The potential downside is that you have the dramatic backlash among young women and young queer people, who tend to vote at a higher rate and participate in politics at a higher rate,” said Deckman. “The backlash to that normalizing rhetoric of hypermasculinity and saying that the left is targeting men and hates men—I think the reality is, that also stands to, in fact, solidify more support for Democrats and for Harris among young voters overall.”