In politics, history has a way of repeating itself with a twist. Eight years ago, the media was drenched with leaked emails from Hillary Clinton’s campaign, a flood that may have tipped the scales in Donald Trump’s favor. Fast-forward to 2024, and we find ourselves in a bizarro version of that same story. This time, it’s the Trump campaign allegedly falling victim to a hack, with internal documents hitting journalists’ inboxes. But unlike the frenzy of 2016, major news outlets have chosen to sit on this information, only revealing its existence weeks after the fact. Hmm.

This dramatic shift in approach raises a serious question: Has the media learned from its past mistakes, or is this an overcorrection in a way that, once again, just happens to benefit Donald Trump? Meanwhile, the frustrating reality is that the public is largely in the dark about the decision-making processes behind these changes. While restraint in publishing potentially hacked materials can be commendable, the lack of transparency about this evolving practice is more than a little troubling.

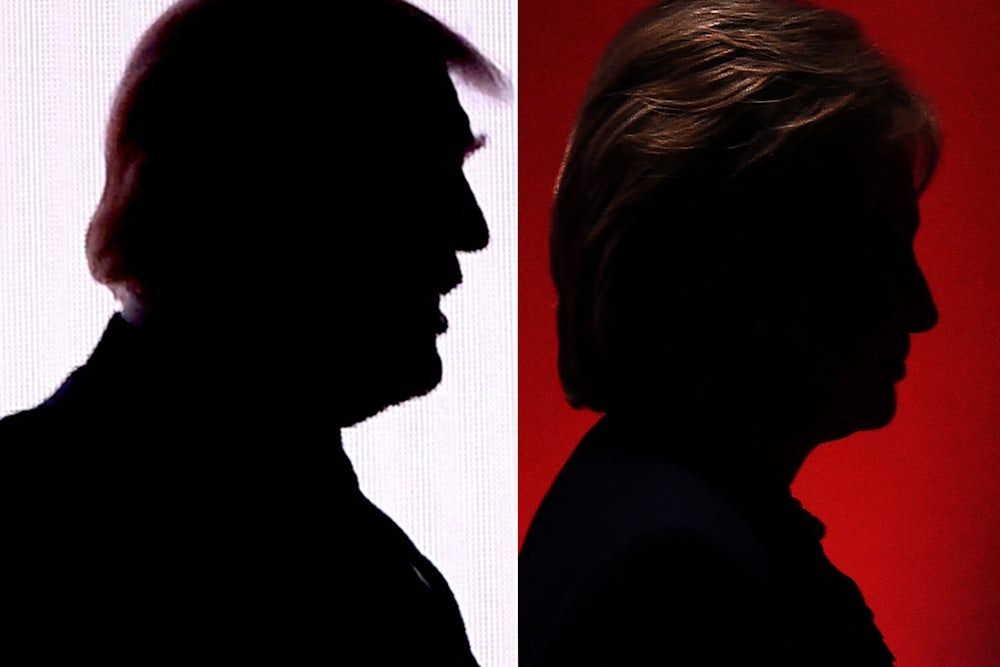

I want to look at some of the similarities and differences between the 2016 and 2024 hack-and-leaks and try to understand why they’re being treated differently.

First, let’s look back at the 2016 leaks and how the press covered them.

In the summer of 2016, the Democratic National Committee discovered that its emails had been hacked. On July 22, just days before the start of the Democratic National Convention, WikiLeaks published nearly 20,000 emails stolen from DNC servers. These emails typically contained conversations between DNC staffers and insiders. There was a fair amount of embarrassing, if not entirely damning, content in the leaks. For instance, the leaks gave a behind-the-scenes look at how donors essentially buy access to politicians and made clear what was pretty obvious: DNC leadership were not exactly fans of Bernie Sanders.

In October, WikiLeaks began releasing emails stolen from the personal account of John Podesta, Clinton’s campaign chairman. Over the course of the month, WikiLeaks published more than 50,000 of Podesta’s emails in daily batches, keeping the story in the news cycle right up until Election Day.

The media’s response to these leaks was … pretty intense. According to a study by Media Matters, in the five weeks leading up to the election, weekday evening cable news aired a combined 247 segments either about the emails or featuring significant discussion of them. Major newspapers published nearly 100 articles about the WikiLeaks emails in their print editions during the same period.

The coverage wasn’t just high-volume; it was sensationalized. Many outlets focused on cherry-picked quotes taken out of context, fueling controversy and speculation. The constant drip of new information kept the story alive, dominating headlines and shaping the narrative of the campaign’s final weeks.

While there were early suspicions of Russian involvement in the hacks, many media outlets initially treated the leaks primarily as a political story rather than a potential act of foreign interference. It wasn’t until after the election that the full scope of Russia’s role in the hacking and distribution of these emails became clear.

The damage to the Clinton campaign was extraordinary. WikiLeaks’ slow-release approach forced journalists to cover each batch as new “revelations,” even when there wasn’t much to actually cover. Having learned through bitter experience that few Americans would bother to actually read them, WikiLeaks sprinkled emails into the news cycle and gave Americans the impression of a campaign wound so deep it couldn’t heal. While Donald Trump rapid-cycled through scandals that seemed not to stick because they were so quickly displaced by fresh ones, “the emails” lingered in the public eye.

The effect was devastating. By artificially prolonging the story, WikiLeaks conveyed the impression of wrongdoing so deep it transcended the amnesia we’ve come to expect from the news cycle; of a grievous wound that wouldn’t heal and which—if we ever bothered to actually take a look at it—we’d find shocking indeed.

The press absolutely helped Assange and WikiLeaks achieve his unstated objective of tanking Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign and elevating Trump to the presidency. There’s really no question about that.

So, surely, the press would issue some sort of mea culpa for effectively handing Trump the presidency, yes? Surely, this would mean the return of the ombudsman and public editor roles at organizations, yes? Ha! No such luck! Instead, the best we got was a December 13, 2016, New York Times article by Eric Lipton, David E. Sanger, and Scott Shane that included the line, “Every major publication, including The Times, published multiple stories citing the D.N.C. and Podesta emails posted by WikiLeaks, becoming a de facto instrument of Russian intelligence.”

Other than that? Good luck.

Now let’s look to 2024 and examine the alleged hack of the Trump campaign.

In late July and early August of this year, several major news outlets, including Politico, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, received emails from a mysterious figure calling himself “Robert.” This individual offered internal Trump campaign documents, most notably a 271-page dossier listing J.D. Vance’s potential vulnerabilities as a running mate. Unlike in 2016, when similar leaks were quickly published and dissected, these news organizations chose a different approach.

For weeks, these outlets sat on the information, conducting their own investigations and deliberations. It wasn’t until August 10 that the story broke, not with the content of the leaks but with news of the hack itself. The Washington Post reported that the Trump campaign claimed to be “the victim of a foreign hack,” pointing to a Microsoft report suggesting Iranian involvement.

The media’s restraint has been notable. As Will Sommer and Elahe Izadi reported in the Post on August 13, “So far, newsrooms have been reluctant to run with the material.” Instead of publishing the leaked documents, news organizations have focused on the hack itself and the potential implications of foreign interference.

This cautious approach represents a significant shift from 2016. Matt Murray, executive editor of the Post, explained their reasoning: “This episode probably reflects that news organizations aren’t going to snap at any hack that comes in and is marked as ‘exclusive’ or ‘inside dope’ and publish it for the sake of publishing.” He added, “All of the news organizations in this case took a deep breath and paused, and thought about who was likely to be leaking the documents, what the motives of the hacker might have been, and whether this was truly newsworthy or not.”

The decision not to publish the Vance materials seems to have been influenced by their perceived lack of newsworthiness. Murray noted, “In the end, it didn’t seem fresh or new enough.”

However, this new approach has not been without its critics. Jesse Eisinger, senior reporter and editor at ProPublica, told Sommer and Izadi that the outlets could have told more than they did. He argued that even if past Vance statements about Trump were easily found publicly, the vetting document could have indicated which statements most concerned the campaign or revealed things the journalists didn’t know.

Writing at The Bulwark, Marc A. Caputo, who was at Politico during the 2016 election, made the argument for publishing leaked documents: “Reporters are not in this to worry about partisan critics or holier-than-thou media professors. This isn’t a job to make friends, be extensions of campaigns, or agents of any government. We report news.”

I would say the same thing today. The job is to cover the news. And the Vance dossier sure as hell sounds like news.

Writing at his Off Message Substack, writer Brian Beutler argued that “outlets like The New York Times owe their readers frenzied coverage of his campaign’s emails, or a mea culpa for their history-altering emails fixation in 2016.”

This stands in untenable contrast to the way these same outlets responded to the hacking and leaking of Democratic emails in 2016. A hallmark of Trump-era journalism has been the media’s institutional defensiveness of its conduct in the run-up to Trump’s first election. Precious few reporters have retrospectively acknowledged that their 2016 fixation on emails (both the ones on Hillary Clinton’s personal server and the ones that were stolen from her colleagues) fell beneath professional standards. Most reporters, and nearly all decision-makers, insist they did nothing wrong—at most they’ll allow that their failures that cycle were garden-variety.

“When we learn important things, to not publish is a political act,” the Times’ then-executive editor Dean Baquet insisted in retrospect. “The calculation cannot be, we’re just not going to publish because that would screw up American politics. You know, at that point, I will go into business as like a campaign adviser to people and not as a journalist.”

Oliver Darcy caught up with some veterans of Clinton’s 2016 campaign for a piece over at his brand-new Status newsletter. It’s not that the former Clinton campaign officials believe news organizations should spotlight hacked materials. It’s that, when they protested in 2016, their complaints largely fell on deaf ears. Now, however, it appears the standards have quietly changed without any type of formal mea culpa having been offered by news institutions.

As the former Clinton communications official told me, “To the extent that there is a widespread frustration, the lack of a mea culpa is what is driving people the most nuts.”

I’m with Beutler on this. If the press wants to do things differently this time around, fine. But if they’re going to do that, then they have a responsibility to both explain the change and make it clear that they botched 2016. It’s as simple as that. If they can’t do that, then I think there’s an obligation to treat this leak the exact same way they treated the 2016 email leak: nonstop negative coverage that played up the very existence of a leak as a scandal in itself. But they won’t.

The media’s failure to acknowledge and atone for their role in 2016 election coverage leaves a gaping hole in the public’s understanding of how and why news organizations have changed their tactics. This silence not only undermines trust in journalism but also allows for additional double standards that consistently seem to benefit one side of the political aisle.

If outlets want to adopt a more cautious approach to leaked materials, they have an obligation to explain this change to their readers. More importantly, they need to openly reckon with past mistakes. Without this accountability, the press comes off as uneven and biased, favoring the right.