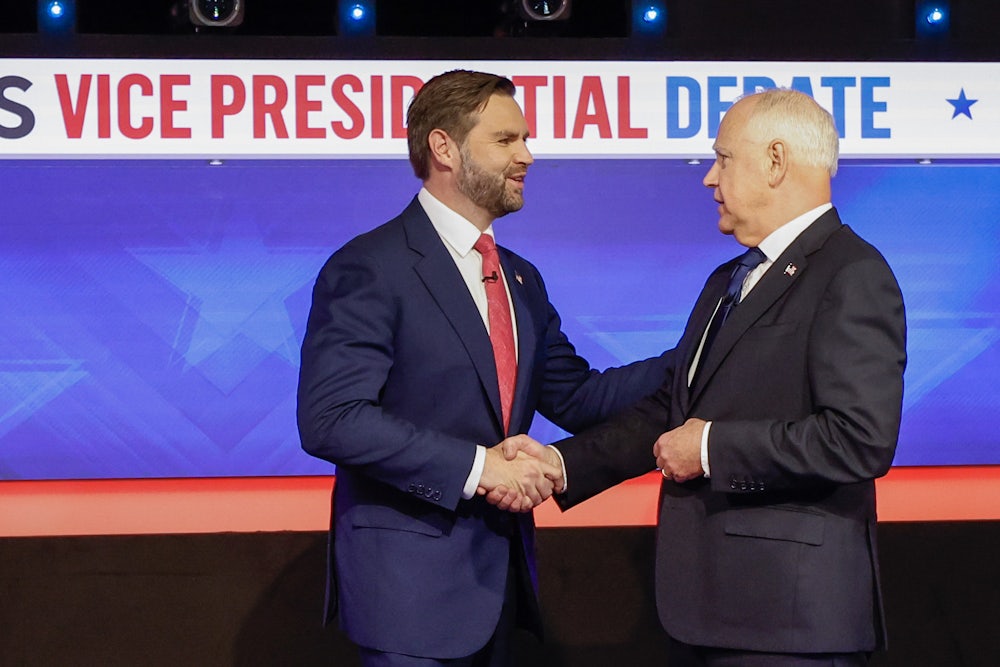

Unlike the contentious debate between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump in September, the debate between their two running mates on Tuesday was relatively mild-mannered, with occasional areas of polite agreement. One such moment of comity between Minnesota Governor Tim Walz and Ohio Senator JD Vance was on the importance of childcare, and the belief that it is overly expensive and difficult for parents to raise children.

“I think there is a bipartisan solution here because a lot of us care about this issue,” Vance said in response to a moderator’s question on childcare. Walz later added that he did not think Vance and he “are that far apart.” The rub, however, lies in how to solve the problem of high childcare costs. Walz and Vance may be further apart than they claim.

Childcare can be massively expensive for parents, comprising a high percentage of a household’s monthly income. Unlike many other developed countries, the United States does not subsidize the cost of childcare facilities. There is also a shortage of childcare workers, and facilities find it difficult to fill openings because of low wages; according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, childcare workers in a professional facility earned an average of roughly $30,000 per year in 2023, less than the average wages of waiters or retail cashiers.

While there may be bipartisan agreement that this is indeed a problem, the parties diverge philosophically on how to fix it, said Oren Cass, the founder of American Compass, a think tank that promotes a more populist interpretation of conservative social policy.*

“The Democratic Party tends to see childcare—meaning the commercial service of somebody taking care of the kids that the family pays for—as a sort of discrete, stand-alone service that government should be providing support for,” said Cass, who previously served as an adviser to Mitt Romney. “I think conservatives are much more reluctant to go in that direction, not because they oppose that but because, I think, they recognize that that is only one of many ways a family might want to arrange parenting and childcare.”

As a modern warrior of the MAGA movement, with the occasional overture to populism that entails, Vance has spoken about childcare access and the role that government should play in ensuring its affordability. At the debate on Tuesday, he highlighted how his own family situation—two working parents—echoed that of many other households, saying that his wife was “an incredible mother to our three beautiful kids but is also a very, very brilliant corporate litigator.” But even someone with all of his wife’s advantages could find it difficult to raise children, Vance continued, arguing that there was “cultural pressure” on new mothers.

“A lot of young women would like to go back to work immediately. Some would like to spend a little time home with the kids. Some would like to spend longer at home with the kids. We should have a family care model that makes choice possible,” Vance said.

In the past four years, congressional Republicans stymied President Joe Biden’s efforts to implement an affordable childcare system and shut down Democratic efforts to reinstate a version of the expanded child tax credit that was temporarily implemented at the height of the pandemic. A bipartisan effort to more narrowly expand the credit was torpedoed by Senate Republicans, and Vance did not attend either vote on advancing the bill.

Nonetheless, at the vice presidential debate, Vance attempted to burnish his bona fides as a Republican committed to easing the burden and expense of parenthood, arguing that the informal networks of childcare should be bolstered by federal assistance. He stayed light on policy specifics but argued that the current childcare programs that primarily assist low-income households “only go to one kind of childcare model.”

He expanded upon an idea that he had previously promoted, in which community or family members would be subsidized by the government for providing childcare assistance. “Let’s say you’d like your church, maybe, to help you out with childcare. Maybe you live in a rural area or an urban area, and you’d like to get together with families in your neighborhood to provide childcare in the way that makes the most sense. You don’t get access to any of these federal monies,” said Vance. “We want to promote choice in how we deliver family care.”

These comments echoed previous statements from Vance. In early September, he told conservative podcast host Charlie Kirk that the cost of childcare could be lessened by having grandparents, aunts, and uncles “help out a little bit more,” and that the federal government could “empower working families” by rolling back regulations and requirements for childcare workers. More controversially, Vance appeared to agree with a podcast host in a 2020 interview that the “whole purpose of the postmenopausal female” was to help raise grandchildren.

“What you see all these Republican proposals leaning toward,” Cass said, “is, let’s actually get the family the resources in a cash payment and let them decide, ‘Yes, we can use this to reduce the cost of childcare, if that’s what we want, but we can also use it to allow us to have a parent working, or we can use it to contribute to some sort of other noncommercial arrangement,’ and then that does a much better job of actually addressing what what families want.”

But Hailey Gibbs, the associate director of early childhood policy at the left-leaning Center for American Progress, argued that the recent Republican proposals on childcare were overly reliant on informal family support, rather than improving conditions for childcare workers who are trained to provide comprehensive early education.

“Not everyone has access to extended family members to help provide care, and asking those family members to do so without pay negatively impacts the economic security of that person for whom retirement might still be out of reach, or health expenses might be quite high,” said Gibbs. A focus on family assistance also “undervalues the crucial work of early educators in the field,” Gibbs continued, which is “educational and developmental support for young children that plays a big role in shaping their trajectory throughout and beyond.”

Gibbs also argued that when Republicans talk about making it easier for parents to stay home after having children, the implication is that it is mothers, specifically, who will stay home to provide the bulk of care.

“I think a lot of conservatives, when they’re talking about the child tax credit, are thinking of it as a way to supplant other levers to support families’ access to care and really reinforce this [one] parent at home, [one] parent in the workforce family model,” said Gibbs. She characterized Democratic policies instead as the ones that offered parents more choice through a “a mixed delivery system that’s not contingent upon family income or geography” but provides options for care from different community, school, and family-based programs.

Republicans have long framed themselves as the party of traditional family values and supported policies that they see as promoting family formation—such as the child tax credit, which congressional Republicans increased in their massive 2017 tax cuts bill. In the two years since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, some conservative organizations have embraced policies to encourage people to have children, such as cash benefits. Vance himself has promoted the idea of increasing the child tax credit to up to $5,000 per child.

“After that decision came down,” said Angela Rachidi, senior fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, referring to Dobbs, “there was a … renewed attention to the ways that public policy can help young families, so that moms might feel like they’re more supported if they wanted to bring a child into the world.”

Harris has proposed capping childcare expenses at 7 percent of household income, although with few specifics on how it would be implemented. She has also endorsed a tax credit of up to $6,000 for newborns, in addition to an expanded child tax credit. Meanwhile, Trump has insisted that somehow his proposal to raise tariffs would boost the economy such that childcare costs would no longer be a factor.

“It’s a very important issue. But I think when you talk about the kind of numbers that I’m talking about that—because the childcare is, childcare, it’s, couldn’t, you know, there’s something, you have to have it. In this country, you have to have it,” Trump said at the Economic Club of New York in early September. “But when you talk about those numbers compared to the kind of numbers that I’m talking about, by taxing foreign nations at levels that they’re not used to, but they’ll get used to it very quickly—and it’s not going to stop them from doing business with us, but they’ll have a very substantial tax when they send product into our country. Those numbers are so much bigger than any numbers that we’re talking about, including childcare, that it’s going to take care.”

Vance defended this logic at the debate, arguing that the plan to “penalize companies and countries that are shipping jobs overseas” would result in a stronger economy. “I think what President Trump is saying is that when we bring in this additional revenue with higher economic growth, we’re going to be able to provide paid family leave; childcare options that are viable and workable for a lot of American families,” Vance said. However, some economists have predicted Trump’s tariff proposals would cause the American economy to shrink, with middle-income Americans paying the brunt of the costs.

At the debate, Walz touted his state’s new paid family and medical leave program, which will go into effect in 2026. The Minnesota government this year also released $6 billion in grants to help fund childcare programs across the state. Making childcare easier to obtain nationwide would mean addressing the issue “at both the supply and the demand side,” Walz said during the debate.

“You can’t expect the most important people in our lives to take care of our children or our parents, to get paid the least amount of money. And we have to make it easier for folks to be able to get into that business and then to make sure that folks are able to pay for that,” Walz said.

What Republican and Democratic proposals have in common, argued Rachidi, is the centrality of the federal government in addressing the problem. “The approach, really from both sides is, ‘Well, how do we just get more government assistance?’” she said.

But that doesn’t mean conservatives are entirely on the same page. Cass said there was an ongoing debate within the Republican Party about what constitutes “welfare,” which has long been a dirty word on the right. He noted that proposals from Republicans to expand the child tax credit generally include work requirements—an area of disagreement with Democrats, who generally believe complete benefits should be available to low-income households regardless of whether a parent is working.

“If your definition of ‘welfare’ is counterproductive, bad incentive programs that discourage work, then this stuff people are talking about now is exactly the opposite,” Cass said about childcare proposals like Vance’s. “If the greater value that you’re focused on is actually supporting families and encouraging family formation and work and self-sufficiency, then this is exactly the type of program you would want.”

* This article originally misidentified Cass’s organization