Every presidential election is about control of the Supreme Court, even if many Americans don’t consciously realize it. By reelecting former President Donald Trump on Tuesday and turning over the Senate to firm Republican control, voters guaranteed that all but the youngest of them will live under a deeply conservative high court for the rest of their lives.

The two oldest members of the court are both conservatives: Justice Clarence Thomas is 76 and Justice Samuel Alito is 74. Since 1990, the average age of Supreme Court justices at the time of their retirement is 83 years old. A Kamala Harris presidency would not have guaranteed that Democrats appointed their replacements, of course, but it would have at least denied the opportunity to Republicans for another four years. That possibility is gone now, and a strategic retirement or two on the court’s right flank is much more likely.

Alito has never publicly discussed his potential retirement, as is typical for the justices. But when he was surreptitiously recorded earlier this year, many court-watchers took note of his wife’s hint that he might not be on the court much longer. “I want a Sacred Heart of Jesus flag because I have to look across the lagoon at the Pride flag for the next month,” Martha-Ann Alito said in the recordings, referring to controversies over flag-flying at their house and her discussions with her husband about it. “I said, ‘When you are free of this nonsense, I’m putting it up.’”

Thomas, for his part, apparently hopes to stay on the court for as long as he can. The New York Times reported in 1993 that he told one of his clerks that he planned to serve on the court until 2034. When asked why that specific year, Thomas’s answer was straight to the point. “The liberals made my life miserable for 43 years, and I’m going to make their lives miserable for 43 years,” he reportedly said.

Even before Tuesday, the judicial math for Democrats was dire. The three justices appointed by Trump in his first term were young by judicial standards: Justice Neil Gorsuch was 49 years old at the time of his confirmation, Brett Kavanaugh was 53, and Amy Coney Barrett was 48. All three of them could easily serve on the Supreme Court until the 2060s, and their replacement of older justices meant Democrats already faced a difficult path to flipping the court to the liberals within the next 10 to 15 years. That time horizon is now closer to 30 or 40 years.

Trump’s inauguration in January will have an immediate impact on the court’s work. The justices have already heard oral arguments in nine cases where the Biden administration is a plaintiff or a defendant. More are on the court’s docket for the months to come. Not all of them will be affected by the change in administrations, but cases on environmental law and the Second Amendment could see the Trump Justice Department revise the government’s position.

An open question is how much the justices will intervene in some of Trump’s policy plans. Some of his proposals, such as a purge of the federal civil service, are legally dubious. There will almost certainly be court battles over his mass deportation plans and his proposed invocation of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to carry them out. Congress sets the federal budget, not Elon Musk. It is hard to imagine that the justices will exert themselves to constrain Trump on some of these policies, especially when he now has a clear democratic mandate to enact them.

In the long term, the court’s conservative majority will likely continue its ongoing work. The justices will make it easier to limit or scale back federal regulations. Civil rights laws will come under challenge; the court has already teed up a case that could make it impossible to challenge racial gerrymandering via the Voting Rights Act. More ambitious goals, like enshrining fetal personhood in the Constitution or overturning the ruling that protects same-sex marriage nationwide, could now gain traction in the conservative legal movement.

The Trump-era elections have highlighted a deeper shift in how the court and its members understand their roles in public life. Supreme Court justices serve until retirement or death. For most of the post–World War II era, it was retirement. Between Chief Justice Fred Vinson’s death in 1946 and Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s death in 2005, sixteen members of the court left it through retirement or resignation and none died on the bench.

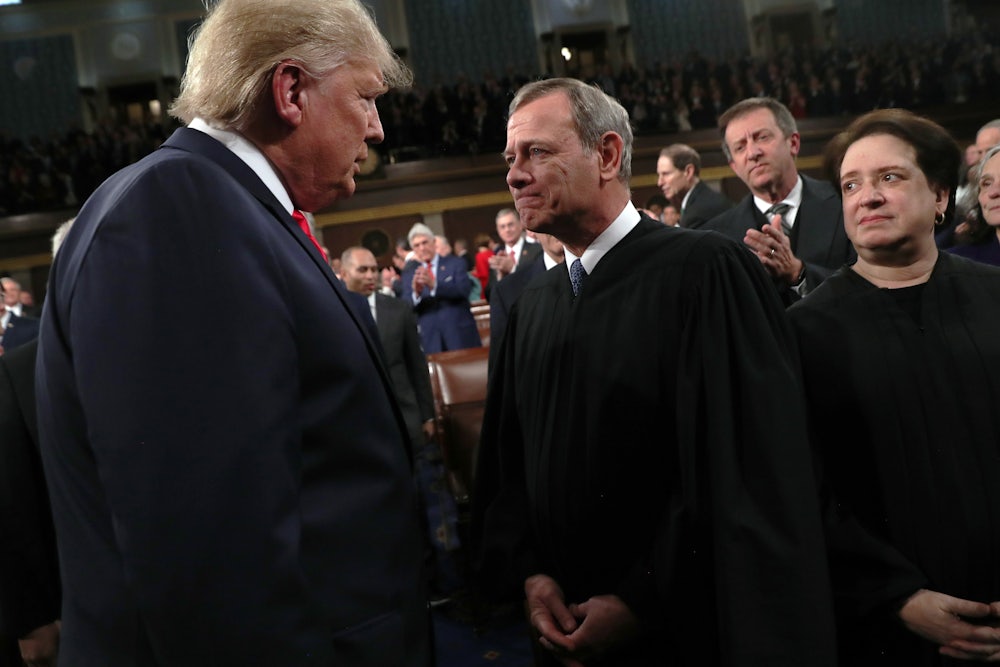

That dynamic changed in the last two decades. Liberal and conservative justices alike took greater care to strategically time their retirements to ensure an ideologically similar successor would be appointed by a sympathetic president. Sometimes they succeeded. David Souter and John Paul Stevens stepped down during Barack Obama’s first term in office, allowing him to appoint Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan to the high court to bolster its liberal bloc.

But there are some things beyond even a justice’s control. Antonin Scalia’s sudden and unexpected death in 2016 raised the prospect that Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential nominee that year, would appoint a fifth liberal justice to the Supreme Court, giving the court its first liberal majority since the 1960s. Republicans rallied around Trump to forestall that possibility. Ruth Bader Ginsburg resisted calls from some Democrats to step down for health reasons in 2014 and died six weeks before the 2020 presidential election. Though Joe Biden won that race, her untimely death meant that Trump appointed Amy Coney Barrett to replace her.

Those twin deaths had a long-term impact on the Democratic Party’s psyche. Out of fear of slipping to a 7–2 minority (or worse) under Trump, some on the left no doubt will push for Sotomayor, who is only 70, to retire during the lame-duck period while Democrats still hold the White House and Senate. I’ve written before about how pointless these calls would be and how little they would matter if Trump wins the 2024 election. For one thing, Sotomayor has shown no interest in retirement and has no publicly known health issues that would make it particularly urgent. More importantly, West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin effectively ruled it out in March by promising to block any nominee who lacked GOP support.

The future for how Democrats engage with the court in general is also uncertain. In recent years, some of the court’s critics proposed sweeping reforms that would add more justices to explicitly reverse the Trump-era majority. The Biden administration tolerated those suggestions if only to ultimately suppress them. If Democrats ever regain power at the federal level, similar proposals might be floated again. But even Franklin D. Roosevelt, who wielded legislative majorities unlike any president before or since, found himself unable to pack the court in the late 1930s.

It is doubtful that any future Democratic president will be more successful now. Two of the last three presidential elections were, at least in part, referendums on the future of the Supreme Court—who would control it in 2016, and whether it had gone too far in 2024. Democrats lost both of those contests. The justices are not on the ballot themselves, of course, but they are not ignorant of public opinion. It will be hard for them to take any message from Tuesday’s results other than this: Full steam ahead.