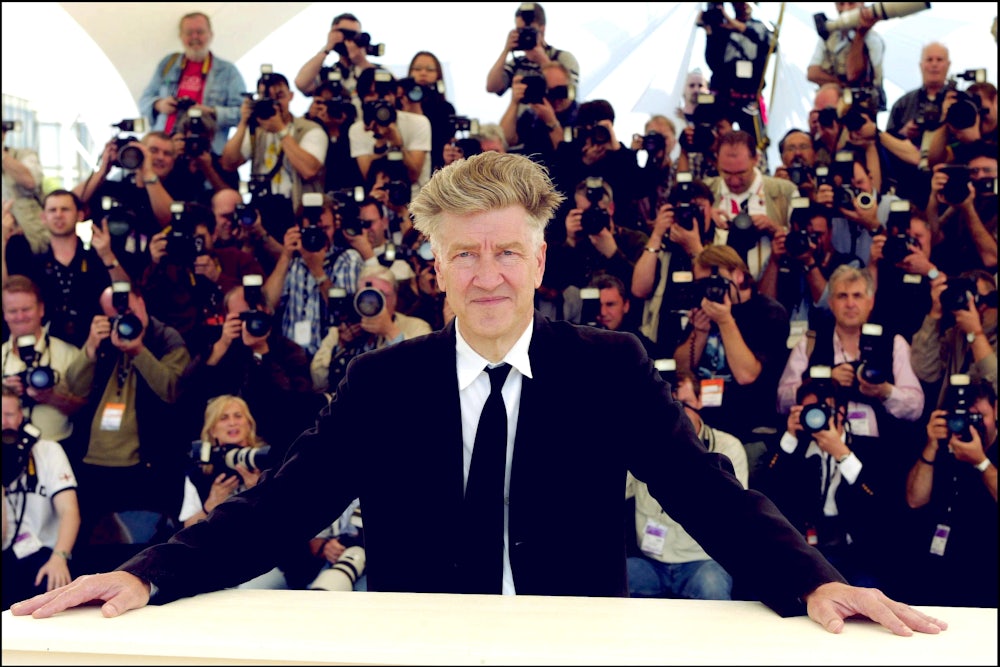

The Fabelmans, Steven Spielberg’s 2022, barely coded biopic of his own artistic adolescence, ends with a young Sammy Fabelman (the Spielberg stand-in) granted an audience with his hero, the legendary American director John Ford. Sitting in a dim office in trademark ball cap and eyepatch, puffing on a big cigar, Ford is played by another fabled American filmmaker—David Lynch, who passed away Thursday at 78, following a struggle with emphysema.

As Ford, Lynch orders the young Fabelman around his office, barking at him to describe the horizon lines of a bunch of Western vista paintings hanging on his walls. “Now remember this,” the elder statesman says. “When the horizon’s at the bottom, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s at the top, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s in the middle? It’s boring as shit!”

At first blush, it was a weird cameo. It would be hard to think of two American filmmakers of the same generation who have less in common than Steven Spielberg and David Lynch, at least in the final analysis. Granted, both have a dweeby, Boy Scout quality. (Indeed, Lynch reached the rank of Eagle Scout as a boy, and Spielberg has thanked the outdoorsy org for catalyzing his interest in moviemaking, thanks to its Photography merit badge.) Both are obsessed with broken homes, and busted-up family dynamics. But where Spielberg’s cinematic project (at least pre-9/11) was the restoration of some bygone feelings of family, togetherness, and order, Lynch plumbed into the murkier depths, from which Spielberg and his ilk long recoiled.

Born in Montana in 1946, Lynch’s early artistic ambitions led him to Philadelphia, where, in 1965, he enrolled at the (recently shuttered) Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. There, Lynch messed around with sculpture and mixed-media projects, producing early shorts Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times), and The Alphabet. In his 1970 short The Grandmother, a young boy pots a weird seed in his bedroom and grows a nagging maternal babushka, with the hope that she’ll protect him from the quarreling family dynamics raging below. From Freud, these works borrowed a deep psychosexuality, framing the nuclear family as perverse; from Francis Bacon, Lynch lifted a sense of human beings as revolting monstrosities. The work was abject, nauseating, and funny.

As influential to Lynch as his early cinematic forays was the city of Philadelphia itself, which the young artist described (in the sort of comment a proud Philadelphian may take as a backhanded compliment) as “one of the sickest, most corrupt, decadent, fear-ridden cities that exists.” This mood—palsied, perilous, postindustrial—hung over Lynch’s feature film debut, 1977’s Eraserhead. The film is a parable of anxious fatherhood, featuring a dork in a high pompadour tending to a mutated newborn whose sorrows are eased by a chipmunk-cheeked singer who lives in his radiator. It became a regular fixture in the midnight movie circuit, playing to generations of late-night crowds, buzzed on pot and low-dose surrealism.

After Eraserhead, Lynch’s reputation as an oddball loomed large. And sometimes in ways that did a discredit to his art. His well-earned renown as a conjurer of campy and self-consciously “weird” images—a lady in a radiator, a little person in a cherry-red suit dancing madly, an eyebrow-less Mystery Man (played by Robert Blake) cackling into a ’90s portable telephone, a sinister cowboy berating Justin Theroux at an abandoned Hollywood Ranch, a spinster in a chunky sweater communing with a log—could itself be flattened into kitsch; reproduced as T-shirts and enamel pins and memes proliferating across social media. His body of work could evoke the uncharitable description offered by Moe, the grumpy bartender from The Simpsons, when asked to define postmodernism: “weird for the sake of weird.” Countless imitators who have striven to reproduce truly Lynchian images—i.e., those that juxtapose the menacing against the everyday, the banal with the surreal and sublime—risked making the director’s approach look like little more than a bag of tricks. Scratch such superficial surfaces, however, and (in Lynchian fashion) an even more revealing underbelly appears.

What is most discomforting about Lynch is not his foregrounding of abuse, venality, or the general rot that gnaws away at the edges of America’s middle-class, white-picket-fence fantasies. It is his profound—and profoundly unfashionable—moral seriousness. His is a moral cosmos of right and wrong, of virtuous good, railing against a more seductive, corrupting inequity. The conflict is explored at length in his ABC (and, later, Showtime) primetime soap, Twin Peaks. It is ostensibly a straightforward detective drama, about the eccentric FBI agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan, whose boyish charm and square-jawed good looks made him a recurring Lynch proxy) dispatched to a small Pacific Northwest town to solve the murder of a high school prom queen, Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee). In the process, Cooper unravels an epic, dimension-spanning battle over the souls of man, waged by daemonic inhabits of a hellish “Black Lodge” and the more angelic agents of the “White Lodge.” Cooper’s quest, more than solving the murder, is about navigating the tension between these realms of unambiguous good and evil.

This clear-cut delineation between right and wrong—combined with the artist’s “gee golly” affect—have led certain critics to brand Lynch and his work reactionary. Owen Gleiberman, writing in Variety, called Lynch an “ironic cultural conservative” who “dug President Reagan for the same reason that he loved sitting in diners in L.A. drinking milkshakes and coffee: It made him feel that the ’50s of his youth was still going on, that Fortress America was still there to protect him.” Roger Ebert, another longtime Lynch-agnostic, was galled by the provocations and violence of 1986’s Blue Velvet, which set “cold-blooded realism” against “deadpan irony.” “What are we being told?” Ebert wondered, rhetorically, in a pan. “That beneath the surface of Small Town, U.S.A., passions run dark and dangerous? Don’t stop the presses.” (Ebert, and a great many others, would come around by the time of 2001’s tinseltown fantasia Mulholland Drive, which is about as fine a film as has ever been made in America, or anywhere.)

Certainly, Lynch’s nostalgia for diners, milkshakes, poodle skirts, and all that Malt Shop Memories nonsense could scan as a little regressive. His treatment of his female characters, who were almost always imperiled, only to be rescued by do-gooder men embracing their role as white knight, could also seem oldfangled, even totally sexist, were it not tinged by that trademark irony. (His 2006 avant-garde baffler Inland Empire was released with the tagline “A Woman in Trouble.” It might well double as a title for a career retrospective.) Perhaps it is a function of Lynch being so steeped in signs, stereotypes, and clichés—the Boy Scout, the Good Girl, the Femme Fatale. But whatever one makes of these characters and scenarios, it is clear that Lynch, especially late in his life, complicated them.

In 2017, Lynch would return to the sylvan landscape of Twin Peaks for the limited event mini-series Twin Peaks: The Return. Released at a time when a spate of mothballed TV shows were greenlit for cash-in comebacks, the long-gestating third season made every effort to frustrate the expectations of viewers. If the original series was, in a way, about nostalgia, then The Return was about the corrupting power of the same.

For the first 16 episodes, Kyle MacLachlan’s fan-favorite Dale Cooper lies comatose. In the season’s stunning finale, a revived Agent Cooper enters another dimension, in a last-ditch effort to save Sheryl Lee’s Laura Palmer from her untimely demise. It is a vain attempt at Dudley Do-Right heroism on the part of Cooper, and one that only dooms Palmer, yet again. But the lesson is clear.

The Return unfolded less like another ironic satire (of TV reunions, this time) and more like Lynch’s mea culpa, reconciling his own compulsive tendency to circle back to these narratives of women in trouble. As it stands, The Return is Lynch’s final piece of work. And it’s a perfect capstone to a career marked by dizzying, dreamlike creative highs: one that embodies, complicates, and crucially thinks through the assumptions of his own art, and of the all-American myths undergirding it.

Still, perhaps the best—and certainly more comforting—final image of Lynch is his turn as John Ford in Spielberg’s movie: a master of American cinema playing a master of American cinema, in a film by another master of American cinema, about the genesis of his own cinematic mastery. A seemingly random, throwaway role, it typified Lynch’s approach to art and creativity. His choices were always eccentric and unexpected. And, following John Ford’s dictum, Lynch always committed to a deep consideration—and expansion—of the horizons of the medium, its artistic and commercial potential, and the audience’s ability to vibe on his particular wavelength. David Lynch was fundamentally, temperamentally, incapable of ever being boring.