It took 51 years for the Justice Department to build its tradition of political independence. It took President Donald Trump and his allies roughly three weeks to demolish it. Through a series of orders, memos, and actions since Inauguration Day, the second Trump administration has successfully demolished the post-Watergate norm that federal prosecutors should operate according to the law and without regard for partisan demands by the White House.

Nothing symbolized Trump’s victory over those norms like the department’s decision to drop charges against New York City Mayor Eric Adams. Federal prosecutors had charged Adams with a variety of corruption-related charges last year for his interactions with the Turkish government. After Trump’s victory in November, the embattled mayor traveled to Mar-a-Lago to cozy up to the president-elect, for purposes that were transparently—hilariously—obvious.

Mission accomplished: On Tuesday, the government dropped the case against Adams. Emil Bove, the acting deputy attorney general, ordered the federal prosecutor’s office in Manhattan to dismiss the charges without prejudice, meaning they could theoretically be refiled in the future. His memo instructed prosecutors that there was to be “no further targeting of Mayor Adams or any additional investigative steps” before the department conducts a deeper review after this year’s mayoral election.

Bove made clear that the department had “reached this conclusion without assessing the strength of the evidence or the legal theories on which this case is based.” Instead, it argued that dismissal was necessary on policy grounds. “The pending prosecution has unduly restricted Mayor Adams’ ability to devote full attention and resources to the illegal immigration and violent crime that escalated under the policies of the prior administration,” Bove wrote.

If this sounds suspiciously like a corrupt quid pro quo, then Bove is more than eager to put a reader’s mind at ease. In a footnote, Bove wrote that the federal prosecutor’s office in Manhattan had written a memo noting that Bove himself had told Adams’s lawyers that “the government is not offering to exchange dismissal of a criminal case for Adams’s assistance on immigration enforcement.” Adams, for his part, has now reportedly directed city officials to do more to help the Trump administration.

This is apparently how things work now. Gone are the days when Americans could assume that federal prosecutors were applying the law without fear or favor to people who violated it. Trump has achieved his long-sought goal of turning the department into a vehicle for his personal passions—and what’s left of the rule of law will suffer for it.

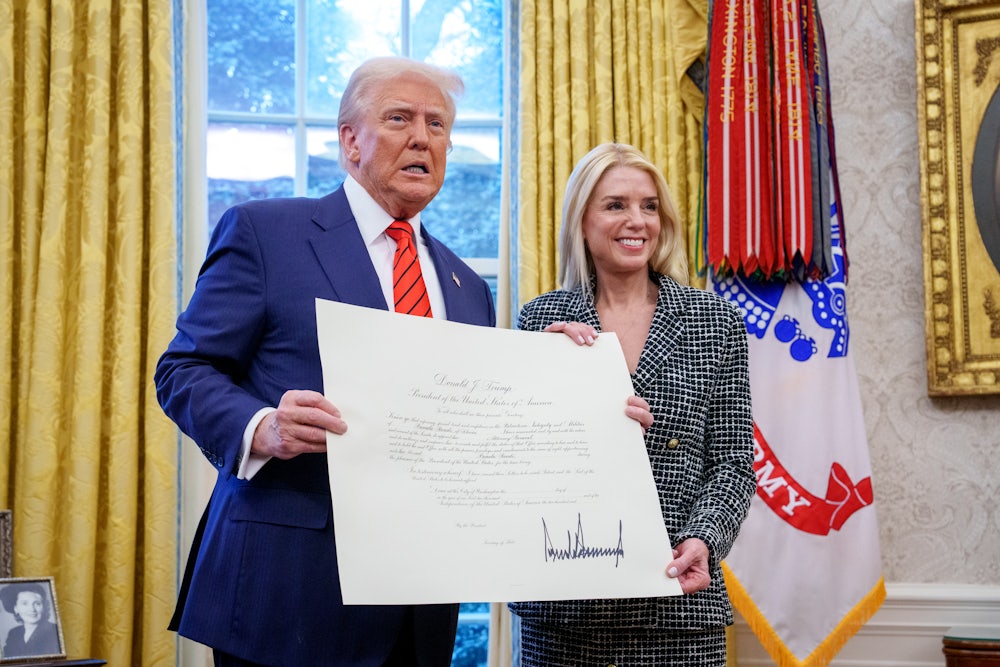

Attorney General Pam Bondi, who took office last week after the Senate voted to confirm her, has already sent out a wave of memos to reshape the department in Trump’s image. Some of these memos reorient the department’s priorities toward Trump’s policy agenda. This in and of itself is not unusual, though Bondi and Trump are more aggressive about it than most.

In a February 5 memo, for example, she directed the Civil Rights Division to “investigate, eliminate, and penalize illegal DEI and DEIA preferences, mandates, policies, programs, and activities in the private sector and in educational institutions that receive federal funds.” Trump had previously ordered all federal agencies to identify potential targets for civil and criminal penalties.

In another memo, she redirected the department’s Fraud Section away from its traditional work and more toward prosecuting cartels and other international criminal groups. She also disbanded the units and task forces that sought to seize and impound Russian oligarchs’ assets after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Those steps follow another one of Trump’s priorities: weakening or erasing federal laws that tackle corruption and ethics violations. Earlier this week, Trump issued an executive order that barred the Justice Department from enforcing the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, or FCPA, altogether. That law generally prohibits U.S. citizens and business from bribing foreign officials.

While the White House framed the order as a temporary pause, the president’s language suggested that he opposed the law’s enforcement altogether. “Many, many deals are unable to be made because nobody wants to do business, because they don’t want to feel like every time they pick up the phone, they’re going to jail,” Trump reportedly said when signing the order, according to CNBC.

Bluntly directing the department to not enforce a long-standing federal law is an extraordinary step. But Trump has long made it clear that he hoped to bring the Justice Department to heel. His experience with the Russia investigation during his first term, as well as his subsequent prosecutions after leaving office in 2021, amplified that hostility. He frequently cast himself as the victim of “witch hunts” and politicized prosecutions, regardless of the evidence against him.

Other memos signal that there will be no room for dissent or autonomy under this new regime. Justice Department attorneys have long enjoyed the informal ability to decline to sign certain briefs on conscience grounds. One of Bondi’s memos, as first reported by Chris Geidner at Law Dork, put an end to that tradition. “When Department of Justice attorneys, for example, refuse to advance good-faith arguments by declining to appear in court or sign briefs, it undermines the constitutional order and deprives the president of the benefit of his lawyers,” the memo said.

“It is therefore the policy of the Department of Justice that any attorney who because of their personal political views or judgments declines to sign a brief or appear in court, refuses to advance good-faith arguments on behalf of the administration, or otherwise delays or impedes the Department’s mission will be subject to discipline and potentially termination, consistent with applicable law,” her memo concluded.

To that end, Trump has transformed the Justice Department into something resembling a personal law firm. Bondi is a longtime ally of Trump dating back to before his presidential campaign. Bove, whom Trump nominated to serve as principal assistant deputy attorney general, worked on Trump’s legal defense teams after Trump’s first term. Todd Blanche, Trump’s nominee to be the permanent deputy attorney general, also worked on his defense team. John Sauer, who represented Trump in the immunity case, is slated to be the next solicitor general.

Bondi has also set up an ironically named “Weaponization Working Group” to investigate the people who prosecuted and investigated Trump. “No one who has acted with a righteous spirit and just intentions has any cause for concern about efforts to root out corruption and weaponization,” she wrote in the memo announcing the move. “On the other hand, the Department of Justice will not tolerate abuses of the criminal justice process, coercive behavior, or other forms of misconduct.”

The president and his cronies had help dismantling the Department of Justice. In Trump v. United States last year, Chief Justice John Roberts essentially nullified the department’s traditional independence. Then–special counsel Jack Smith had alleged in an indictment that Trump had improperly demanded that Justice Department officials publicly support his false claims of voter fraud. Roberts, in his majority opinion, held that these demands weren’t improper at all.

“The indictment’s allegations that the requested investigations were ‘sham[s]’ or proposed for an improper purpose do not divest the President of exclusive authority over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials,” Roberts wrote. “And the president cannot be prosecuted for conduct within his exclusive constitutional authority. Trump is therefore absolutely immune from prosecution for the alleged conduct involving his discussions with Justice Department officials.”

No one has ever disputed that presidents can fire top Justice Department officials, of course. The problem with Richard Nixon’s Saturday Night Massacre wasn’t that he lacked the legal power to oust Attorney General Elliot Richardson, Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus, or special prosecutor Archibald Cox. The problem was that ousting them was a nakedly corrupt act by Nixon, one in which he abused his powers as president to further his personal self-interests.

In other words, this isn’t about what a president can do, but what a president should do. For the last half-century, that meant avoiding the appearance or reality of corruption that comes with letting the White House exercise prosecutorial discretion in politically sensitive cases. Trump, Bondi, and Roberts have sent a very different, very Nixonian message to the Justice Department and to the American people: When the president does something, it’s not corrupt and it’s not a crime. What this heralds is a heyday for corruption and criminality.