When Hasib Satary and his family arrived in the United States on August 27, 2021—less than two weeks after the fall of Kabul—he was in dire need of resettlement services. It had been a stressful 10-day journey for Satary, a former U.S. Embassy employee in the capital of Afghanistan. His travels took him from Kabul to Doha, Qatar, before he finally landed at Dulles International Airport in northern Virginia to begin a new life.

To his relief, the anxiety of arrival was eased by the welcome Satary and his family received from the local community, as well as the assistance of the Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area, or LSSNCA, a refugee resettlement agency offering services in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. The organization helped Satary with finding a home and employment, and aided in enrolling his three children in school. The services were especially needed for his wife, who was pregnant at the time.

“I had no idea where to go, how to go when I was here. But these individuals in the LSSNCA were very supportive, helping me, showing me, taking me to the hospital, taking my wife to hospital,” Satary recalled. “It could [have been] very difficult for me if I didn’t have that support.”

Now, nearly four years after arriving in the U.S., Satary works for LSSNCA as the director of employment services in its northern Virginia office. He helps fellow refugees of all backgrounds find employment, become self-sufficient, and integrate into their communities.*

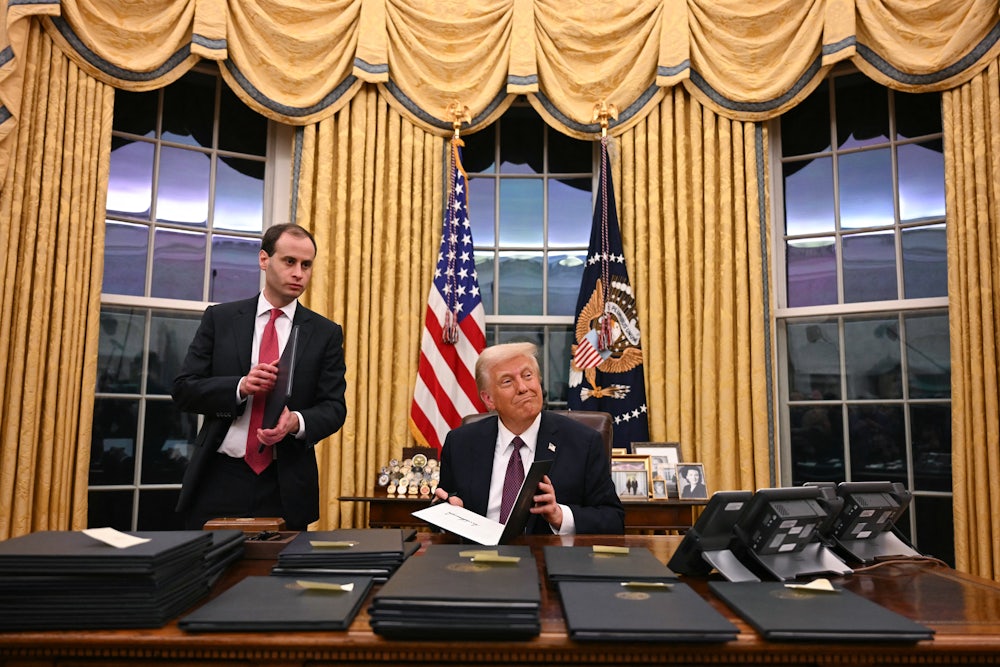

But the assistance that was so vital to Satary and his family in 2021 is no longer available to new arrivals in the United States. After taking office on January 20, President Donald Trump signed an executive order suspending all refugee admissions. Refugees outside of the U.S. who had already received approval to enter the country were blocked from arriving. Shortly thereafter, the administration suspended federal funding for the 10 national agencies that shoulder the burdens of refugee resettlement, most of which are faith-based. This severely disrupted these organizations’ ability to provide services to already-arrived refugees.

Kristyn Peck, the executive director of LSSNCA, recalled receiving the stop-work order from the federal government on January 24, ordering the halt of resettlement services. “We had welcomed 369 individuals through the U.S. Refugee Assistance Program within the previous 90 days who were now immediately no longer eligible for those services,” Peck said. As a result, LSSNCA laid off 42 staff members the following Monday, primarily case management staff. These workers would have been the main point of contact for those recently arrived refugees—75 percent of whom were Afghan.

The administration’s actions have been devastating for the recently arrived Afghans. “They heard the services that people like myself and people who came earlier received—services that they are not going to receive—which is threatening their morale,” Satary said. He recalled a recent meeting with an Afghan man with seven children, who was weeping because he did not receive the resettlement and placement services, as they had been eliminated by the Trump administration—a common source of despair for many new arrivals in the region.

“They are saying it is really an injustice and unfair, the way they are being treated here,” Satary said. For many of these newly arrived refugees, they are caught between a government in Afghanistan that could have them killed and an American government that is suddenly uninterested in providing support.

The Trump administration’s actions on refugee resettlement were swiftly met by lawsuits, some of which are still wending their way through the court system. An appeals court ruled last month that the Trump administration could stop approving new refugees for entry but needed to admit those who had already been conditionally accepted before the refugee system was suspended. (Despite the efforts to make it largely impossible for most refugees to enter the U.S., the Trump administration is working to fast-track the admittance of white Afrikaners from South Africa.)

Separately, a district court judge ordered the Trump administration to resume contracts with nonprofits that conduct refugee resettlement. In a status report updating the court this week, the administration’s lawyers said that the contracts would be reinstated and then immediately suspended.

Tens of thousands of Afghans who were admitted to the U.S. in the immediate aftermath of the American withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 were permitted to enter with humanitarian parole, allowing them to claim temporary residency status. In the years since then, many have traversed difficult legal pathways in an effort to obtain legal permanent residency.

“They’ve applied for asylum, which they were overwhelmingly granted due to the persecution they face back in Afghanistan, but it has been an enormous amount of, you know, time and languishing and legal limbo as those applications work their way through the court,” said Krish O’Mara Vignarajah, the CEO and president of Global Refuge, the parent organization of LSSNCA and one of the 10 national agencies that has long partnered with the federal government to resettle refugees.

Others who served with the U.S. military—such as Satary, who worked as an interpreter from 2003 through 2008—were able to apply for special immigrant visas, or SIVs, allowing them and their spouses and young children to obtain permanent resident status. Some may have obtained their green cards, or still have their applications pending adjudication. Then there are those not eligible for SIVs who are still technically in the U.S. with temporary residency, putting them in a sort of legal purgatory—they could apply to renew their parole, or for temporary protected status.

With the president’s insistence on ending birthright citizenship, and the administration’s willingness to detain and deport residents who were in the U.S. legally, the protections once offered by a green card may not seem so stable anymore.

“This administration is obviously doing so many high-profile anti-immigrant, anti-refugee actions for the purposes of spreading fear and intimidating people,” said Adam Bates, a supervising policy counsel at the International Refugee Assistance Project, which has brought some of the refugee-related lawsuits against the Trump administration. “Even the people who have gone through the process and completed that process, I imagine there’s palpable concern and still just a real lack of certainty about what their status is [and] how secure their status is.”

Although the SIV program has technically not been targeted by the Trump administration, it’s unclear how applicants would be affected by a potential new travel ban reminiscent of the first Trump administration’s partial prohibition on visitors from predominantly Muslim countries. Bates also noted that, despite being distinct from the refugee admissions program, the program relies on much of the same infrastructure, which has now been disrupted.

Moreover, Afghans eligible for SIVs or asylum who remain in Afghanistan are now unsure whether they will be able to make it to the United States. “People need to know what to expect so they can plan for their lives. And that’s the big thing that the Trump administration is not allowing them to do at the moment,” said Shawn VanDiver, the founder and president of #AfghanEvac, a coalition of organizations working to relocate and resettle Afghans in the U.S. “The concerns that we’re seeing are presenting mostly in that vein. Like, ‘Am I going to be able to get my family here, ever?’”

Satary also noted that many Afghans eligible for SIVs are women, who have very few rights under the Taliban government and are unable to even visit a place where they can access the internet to inquire about their status. To many in Afghanistan, and their families in the U.S., it feels like a broken promise.

“I remember when talking to my family and friends in Afghanistan, they were very happy with President Trump coming to power, and they were saying like, ‘Now is the time for us to become free, or at least make our way to the U.S.,’” Satary said. “But now, some of them are sad when they are seeing he’s not even talking about them, he’s not even thinking about them.”

Refugees may find integrating into a new community difficult even under the best of circumstances. There is the high cost of living in the D.C. metropolitan area, the need to obtain employment, the need to obtain transportation to get to that employment, the need for a good line of credit to finance the car they need for transportation to get to that employment. Because it is near impossible to support a family with one income in this area, Afghan women may need to find jobs for the first time in their lives, which could also prove to be a cultural adjustment.

Then there is the emotional turmoil of leaving a country where their lives are at risk for one that no longer feels welcoming. “So many of them experienced trauma in their home country, the anxiety induced by the evacuation, and then now the uncertain future they face. And so we just don’t want to add insult to injury in terms of making their predicament even more precarious as a result of U.S. policy,” O’Mara Vignarajah said.

Struggles relating to health care, employment, and housing are among those that are typically addressed with the assistance of a refugee resettlement agency. Even though a large portion of the federal funds that LSSNCA relies on have been unfrozen, the organization has been deeply impacted by the administration’s actions—the team at LSSNCA has laid off around 75 people since last October, Peck said. “Prior to January 20, we really had wraparound support. We were able to provide for families and individuals that were arriving through the refugee program, and we felt really good about the support we were able to provide folks to transition to a new community and new country,” she said.

Amid the policy changes of the Trump administration, Peck said LSSNCA had focused on “mobilizing volunteers and congregations and multifaith coalitions to support refugees,” which in turn assist with the services that would normally be provided by a case-management team.

The community-level work of volunteers echoes the longtime advocacy of U.S.-based organizations, many of which are veterans groups. Several veteran and faith-based organizations pushed for years for Congress to approve bipartisan legislation called the Afghan Adjustment Act, which would expand the number of people eligible for SIVs and create an easier pathway to residency for Afghans in the U.S. on humanitarian parole.

Even prior to the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, said Bates, “there was so much advocacy to come up with a pathway or a process that will allow folks to enter the U.S. on some kind of permanent pathway, instead of having to parole all these folks.

“It’s not as if folks didn’t see this train wreck coming. I mean, there were years and years of runway. And so it’s that much more frustrating and outrageous that we find ourselves here,” Bates continued.

Satary thinks about some of the American soldiers that he served alongside when he was working as an interpreter with the U.S. military, friends whose deaths he witnessed firsthand when they were killed in action. Now that he lives in northern Virginia, he visits their graves when he goes to Arlington Cemetery. The failure to help Afghans is a betrayal not just of his people, Satary believes, but of those soldiers he considered comrades.

“That’s hurting me,” Satary said. “We served alongside those individuals. But now [the] administration is forgetting us, and maybe that means they are not remembering those soldiers as well.”

* This article originally misstated Satary’s title.