The Trump administration reached what it’s calling a “breakthrough trade deal” Thursday with the United Kingdom. I’m very pleased for the United Kingdom, from which my paternal great-great grandfather Moses Noah emigrated in July 1863 and my maternal grandmother, Jean Robertson, in October 1922. My wife and I recently enjoyed watching the second season of Wolf Hall on PBS. Rule Britannia and all that.

But at the risk of spoiling the party, the U.K. is not a country with which the United States has much of a trade problem. A trade problem, as defined (somewhat simplistically) by the Trump administration, occurs when another country sells more stuff to us than we sell to them. Our biggest trade problem, everyone agrees, is China. China sells us $295 billion more in goods than we sell to them. Slapping a 145 percent minimum tariff on all Chinese goods is not an intelligent solution to the problem, but it is a problem, all the same.

It is therefore good news that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent will finally initiate trade talks with China this weekend—talks that Trump previously claimed were already taking place, but weren’t. One remarkable development since Trump moved back into the White House is that statements from the habitually mendacious Chinese government are now more credible than statements from the president of the United States. But set that aside. If you want to call something a “breakthrough,” sitting down with Chinese trade officials is a much bigger deal than sitting down with a bunch of people who talk like Anthony Hopkins.

We don’t have much of a trade problem with the U.K. because we sell $12 billion more worth of stuff to them than they sell to us. This is our fifth-largest trade surplus, according to The Motley Fool, after the Netherlands ($56 billion), Hong Kong ($22 billion), the United Arab Emirates ($19 billion), and Australia ($18 billion). Most of the other places with which we have trade imbalances are underdeveloped countries.

We don’t have much of a trade problem with the U.K., but the U.K. has a big trade problem with us, because our trade surplus is their trade deficit. Also, we are, among nations, the U.K.’s biggest trading partner, whereas the U.K. is only our seventh-largest trading partner. We’re just not that into them.

Compounding the U.K.’s trade difficulties is Brexit, the U.K.’s spectacularly self-destructive decision to depart the European Union, which took effect in 2020. The U.K. did manage before that breakup to negotiate a free trade deal with the EU, eliminating the risk of tariffs being imposed on its imports or exports to the EU. But even so, the U.K.’s exports to the EU, which (as a bloc rather than a nation) is the U.K.’s biggest trading partner, are down by as much as 30 percent compared to where they would be had Brexit never occurred. This has left the U.K. a bit frantic to cut trade deals elsewhere, and especially with the U.S.

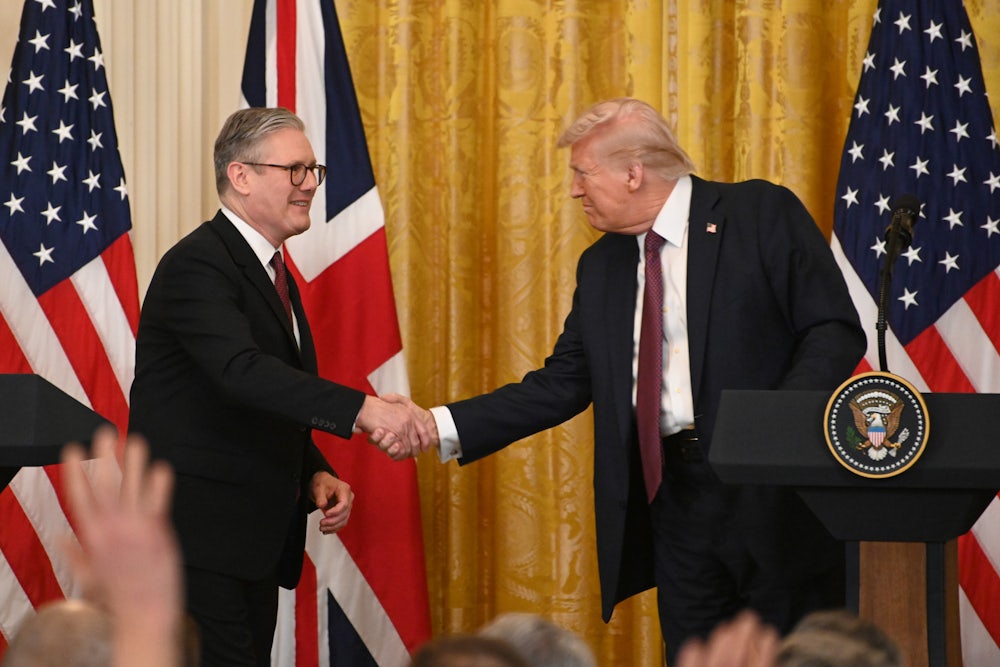

Trump’s trade deal with the U.K., which exists only in rough outline, makes Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s life somewhat easier. Starmer’s diplomatic strategy has been to flatter Trump at every turn—which can’t have been easy for him—and to get King Charles to invite Trump to visit him at Dumfries House or Balmoral Castle, both situated near Trump golf courses in Scotland. This charm offensive has now been rewarded with a reduction in tariffs, from 27.5 to 10 percent, on Jaguars, Land Rovers, and other British automobiles exported to America, and the complete elimination of tariffs on the U.K.’s struggling steel industry. In addition, the U.K. will be permitted to export, tariff-free, up to 13,000 metric tons of beef. All British exports, however, will still be subjected to the same across-the-board 10 percent tariff Trump is imposing on all countries.

In return, the U.S. receives … not much. Some reductions on agricultural tariffs, including tariffs on American beef, although apparently the U.K. will continue not to import any beef from cattle that have been fed growth hormones (the Trump White House refers to this as “non-science-based standards that adversely affect U.S. exports”). There is no deal on pharmaceuticals, on which Trump has threatened to impose a 25 percent tariff. There, the U.S. has a trade deficit of $1.4 billion with the U.K., but the paramount consideration must be to keep it easy to get foreign-made drugs to American patients and American-made drugs to British ones, because human health is more important than political one-upmanship on trade.

The U.S. came into being as a result of a trade dispute with Great Britain, and in those days the game really was rigged to benefit the mother country at the expense of the colonies. Lately, though, the U.S. has had the upper hand—so much so that Trump’s idea of levying heavy tariffs on the U.K. was kind of cruel. The benefit of Trump’s Thursday announcement is mainly that the U.S. can feel a little bit less like the neighborhood bully. That’s worth something. But there’s a reason most of the champagne corks are popping across the Atlantic in this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England. In the U.K., there’s reason to celebrate. Here in the U.S., it’s just another day.