In May 2025, the Asian American Foundation published its fifth annual Social Tracking of Asian Americans in the U.S., or STAATUS, Index. The index, which was launched by the foundation in 2021 in the wake of spiking anti-Asian hate crimes during the Covid-19 pandemic and the Atlanta massacre, compiles surveys on stereotypes and attitudes of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders as reflected in the media and public opinion.

While the data in each report highlights different forms of ongoing discrimination facing Asian Americans, this year’s report included two startling discoveries. Based on a survey of 4,909 U.S. adults ages 16 and above, this year’s report announced that “40 percent of Americans believe that Asian Americans are more loyal to their countries of origin than to the U.S., doubling since 2021.” Within the same survey, 27 percent of respondents stated that Chinese Americans are a threat to U.S. national security.

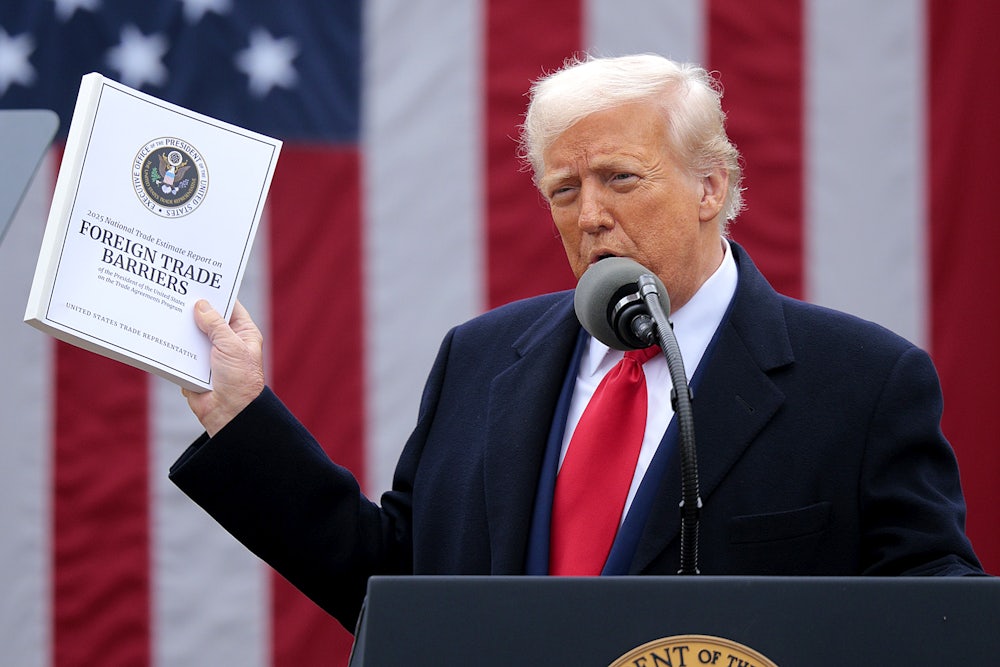

The report touched on the growing rise of xenophobia within the United States during the presidency of Donald Trump, whose policies—most notably his mass deportation schemes and his second trade war with China—have polarized Americans and other nations alike.

Among the policies that have divided the U.S. and the world is Trump’s tariff policy. Tariffs, along with Trump’s push to deport immigrants from the United States, serve as part of an ultranationalist agenda to attack anything “foreign.” Even though international trade or immigrant workers remain an integral part of the American economy, Trump has transformed them into targets for launching his xenophobic campaigns and blames his predecessor, Joe Biden, for whatever ongoing economic turmoil erupts as a result.

While tariffs may not be intuitively xenophobic—Joe Biden levied tariffs on Chinese imports in September 2024—under the Trump administration, they factor into an overt campaign of xenophobia along with his mass deportation policies.

Historically, discussions of tariffs have not always been directly tied to xenophobia, but the debates surrounding each have grown intertwined over the course of the past century. In the history of American economic policy, the tariff has served a variety of uses. In the colonial period through the mid-nineteenth century—before the existence of the income tax—the majority of federal revenue was gathered through tariffs and excise taxes on goods such as alcohol and tobacco.

Yet since the early twentieth century, tariffs have more often coincided with xenophobic policies such as immigration policies that have been implemented under the guise of protecting American citizens from unfair competition. When I asked Douglas Irwin, professor of economics at Dartmouth College and an expert on the history of U.S. tariff policy, whether trade protectionism has often coincided with xenophobia, he noted an important moment in the early twentieth century: “If we look back at history, the trade protectionism of the 1920s and 1930s was co-joined with a policy of isolationism and nativism. So protectionism and nativism are subspecies of xenophobia, and both seem to be making a reappearance today.”

Protectionism has also led Americans to police themselves into demonstrating their loyalty by “buying American.” Historian Dana Frank, the author of Buy American: The Untold Story of Economic Nationalism and more recently What Can We Learn From the Great Depression? notes that “buy American” campaigns can be traced as far as the colonial period, when patriot groups like the Sons of Liberty dumped tea in Boston Harbor in December 1773 in defiance of the British Crown. During the twentieth century, Frank notes, protectionist tariffs during economic downturns, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s and the economic turmoil of the late 1970s and early ’80s, often corresponded with intense nationalism and xenophobia.

For example, in June 1930, Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. Initially crafted by Republicans to win over farmers by cutting down on agricultural imports, the measure eventually expanded to incorporate manufacturing tariffs as well. Although the final bill raised tariffs from 38 to 45 percent, according to Douglas Irwin’s study Trade Policy Disaster, the final result was an immediate decline in dutiable imports by 15 percent and a 5 percent cut in all imports. Canada, Mexico, and Europe all responded with counter tariffs, which in turn led to a deepening of the Great Depression.

As the Smoot-Hawley Act failed to relieve the U.S. of its economic distress, the Hoover administration began to blame immigrants for the nation’s economic woes. Starting in 1930 and ending in 1935, thousands of Mexican immigrants and their American children were blamed for the economic demise of the country. While Wall Street bankers faced few consequences for their actions, Hoover’s Secretary of Labor William Doak used the newly formed Border Patrol, along with local law enforcement, to forcibly repatriate half a million Mexican Americans in the Southwestern U.S. to Mexico.

According to Frank, “Doak announced that the solution to unemployment in the United States was the deportation of illegal immigrants, and his office initiated a sweep of potentially alien seamen. On an even greater and more disastrous scale … Doak supervised the deportation and repatriation of half a million Mexican and Mexican Americans.”

On the West Coast, political leaders took on campaigns that targeted both Asian immigrants and their descendants, as well as goods manufactured in Asia. As with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, white labor leaders supported the Immigration Act of 1924 to block immigration from Asia and impose quotas on new European immigrants. At the same time, newspaper editors described economic competition with Japanese manufacturers as “cutthroat.” In the lead-up to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, politicians regularly blamed Japanese Americans for competing with white farmers. One Salinas farm owner, Ralph Edwin Myers, told Representative John Anderson in February 1942 to remove Japanese Americans from the state and “give the white farmer a chance.”

Dr. Karen Umemoto, the director of UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, has found disturbing parallels between Trump’s rhetoric toward immigrants and the anti-Japanese racism prevalent in 1942: “When a top political leader blames another country for its woes, Americans often scapegoat those around them who ‘look like the enemy.’ We saw this during World War II against Japanese Americans as the U.S. fought against the Axis nations, including Japan. But why are Asians often scapegoated when, in the case of World War II, Germans and Italians were not?”

Even when Japanese Americans were imprisoned in camps, they were still seen as economic competition. For example, in September 1942, a group of Japanese Americans incarcerated at the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming petitioned the government to establish a pottery plant to teach pottery lessons and produce plates for the inmates.

When word got out that a kiln had been purchased by the federal government for the camp, several pottery guilds in Ohio complained that the inmates would produce poor-quality Japanese pottery at cheaper prices. An Ohio congressman, Representative Earl Lewis, made a speech before Congress arguing that the kiln should be cut because these Americans would “return to Japan and add their skill and knowledge of American methods to the already existing Japanese pottery industry … further adding to our troubles in the post-war period by the skills and training which they have acquired while prisoners in an American internment camp.” As a result, the kiln project was canceled.

Anti-Japanese sentiment tied to economics returned famously in the late ’70s, when pundits labeled sales of Japanese cars in the U.S. an attack on the American automobile industry. Attacks became more intense as the U.S. entered a recession in 1980. Headlines like the one on Ira Allen’s March 30, 1980, article for United Press International described the importation of Japanese cars in militaristic terms: “Auto Firms Seek Protection from Japanese Invasion.”

Others, like one in the San Francisco Examiner from April 27, 1982, complained that “Japanese scoff at U.S. complaints of unfair trade practices,” arguing that Japan was unjustly taking advantage of Americans.

Talk of a trade war with Japan fueled anti-Asian racism at home. On the night of June 19, 1982, two white men in Detroit—Ronald Ebens, a Chrysler plant supervisor, and his stepson Michael Nitz—violently murdered Chinese American Vincent Chin. Chin, a Detroit draftsman, was celebrating his bachelor party at a local strip club. A dancer at the club later testified that Ebens shouted at Chin, “It’s because of you little motherfuckers we’re out of work.” Nitz, who was recently laid off from his job as an autoworker, pinned down Chin while Ebens beat him with a baseball bat. Chin died from his injuries at Henry Ford Hospital four days later.

When Ebens and Nitz were tried for Chin’s murder, Wayne County Judge Charles Kaufman refused to sentence the two to prison, instead sentencing them to three years’ probation and a $3,000 fine each. During sentencing, Kaufman said Ebens and Nitz were not “the kind of men you send to jail.” The murder and the subsequent trial became a turning point for the Asian American movement, mobilizing thousands to protest the unjust ruling. (A year ago in June, the Detroit Free Press reported that the FBI quietly released its entire file on the Vincent Chin case. You can read more about it here.)

The full-blown xenophobia promoted by the Trump administration is nevertheless unique and unprecedented in American history. Back in 2018, Tobita Chow wrote for In These Times that the first Trump administration had already begun tying xenophobia to the first trade war: “Trump already started down this road by proposing restrictions on visas for people from China as part of his ‘trade’ fight, while Chris Wray, Trump’s FBI director, recently all but admitted that he is racially profiling Chinese-Americans and Chinese immigrants.” Similarly, New York Times columnist Paul Krugman argued that while it was possible to be “tough on China” back in 2010, when the U.S. rate of unemployment was at 9 percent, the 2018 trade war with China offered nothing but theatrics and economic instability.

While the first Trump administration initiated a trade war with China, the current tariff policies against China build off Trump’s existing anti-Chinese rhetoric from the Covid-19 era. Umemoto has observed how Trump’s current tariff war now recycles his same anti-Asian rhetoric used during the pandemic. “The Trump tariffs come on the heels of the tragic pattern of anti-Asian violence that swept the country with the outbreak of Covid-19 and anti-immigrant scapegoating even prior to 2020,” says Umemoto. “The tariff war has hit many nations, but none more caustically than China. When Covid-19 was coined by Trump as the ‘China virus,’ anti-Asian hate began to spike. And with the tariff war, we sense resentment rising again.”

The combined approach of cutting imports, deporting immigrants en masse, and, more recently, resurrecting Trump’s 2017 travel ban all serve as part of an extreme nativist agenda. Commentators have already noted that the Trump tariffs are not driven to incentivize American manufacturing but are based more on a theatrical display of nationalism. As Jesse Hassenger explained last month in The Guardian, Trump’s 100 percent tariff on foreign-made movies overlooks not only how American companies often use foreign sets for film production but the importance of film as an artistic medium for connecting with other cultures. “It’s a simple-mindedness that many people grow out of—sometimes with the help of exposure to the arts. No wonder the president treats all forms of them with such contempt.”

“Buy American” campaigns work to foster the notion that foreign goods are cheaper and inferior to American ones and that they do a disservice to the American economy. Likewise, the Trump tariffs not only force struggling Americans to bear the cost burden of import goods that are so ingrained in daily American life but also erode trust in international cooperation with the United States. In this way, Trump’s tariff policy marks a sea change for American economic policy as well as another major blow to American diplomacy.

The current trade war has left many Americans angered and confused about the economic future of the country. In the past month, public opinion polls have shown that 60 percent of Americans oppose Trump’s tariffs. The Federal Reserve just released the June edition of its Summary of Commentary on Current Economic Conditions by Federal Reserve District, or Beige Book, which evaluates reports from individual Reserve banks on the status of the U.S. economy. In summarizing prospects for the summer, the report concluded that tariffs would have lasting consequences for the job market and lead to price increases. In describing future trends regarding employment: “Staffing services contacts said that employers across many industries delayed hiring because of uncertainty related to tariffs.” Douglas Irwin recently told The Wall Street Journal that Trump’s current tariff plan “amounts to grossly irresponsible economic management.”

It is important to understand that excessive tariffs, mass deportations that flout the rule of law, and attacks on cultural institutions such as universities are not separate policies but part of a new white nationalist policy to expunge anything labeled as foreign and un-American while doing little to nothing to address the root causes of the growing poverty gap between the majority of Americans and the 1 percent—such as stagnant wages and limited long-term employment. The ensuing tariff war, along with the current federal spending bill, will only result in rising costs for ordinary Americans while enabling corporations to keep wages stagnant. For working-class Americans, the ability to survive a second Trump administration will depend less on where a good is manufactured than on whether the country can hold elites accountable for the growing poverty gap in our nation.

And when such policies fail, Trump will pivot toward theatrics. We are witnessing it firsthand in Los Angeles, where mass ICE raids in immigrant communities followed by the unnecessary deployment of the National Guard and Marines are designed to antagonize rather than to protect. As Trump faces pushback on his tariffs and his spending bill, going after Los Angeles also is, as Matt Ford rightly noted, a sign of weakness. For a city that Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano describes as “everything he [Trump] loathes: diverse, immigrant-friendly, progressive and deeply opposed to him and his xenophobic agenda,” the raids are a calculated attempt to punish and provoke his opponents. To conduct mass raids in L.A. of this scale should be seen as an injustice and an act of desperation.

Trump’s tariffs, like his deportation scheme, may end up being a short-term policy depending on whether it can survive its conflicts with the federal judiciary. And, as Wall Street observers have noted, Trump may just “chicken out” of levying new tariffs to claim a quick victory. But for many immigrants and working-class Americans, the scars of the tariff war will remain long after the policies end.