David Souter, who died on Thursday at age 85, was perhaps the most important Supreme Court justice of the late twentieth century. His appointment to the high court in 1990 was meant to cement the conservative legal counterrevolution, washing away the heady liberalism of the 1950s and 1960s in favor of right-wing constitutional theories.

Nobody seemed to ask Souter if he was interested in such a role in American legal history, however, and when given the opportunity to play it, he declined. Roe v. Wade survived an additional 29 years—more than half of its ultimate lifespan—solely because he defied expectations by not voting to overturn it in 1993. The counterrevolution was not stopped, but it struggled for another two decades until more loyal foot soldiers could be found. Souter was not the most influential or powerful justice of his era, but he may be the one most essential to understanding the court today.

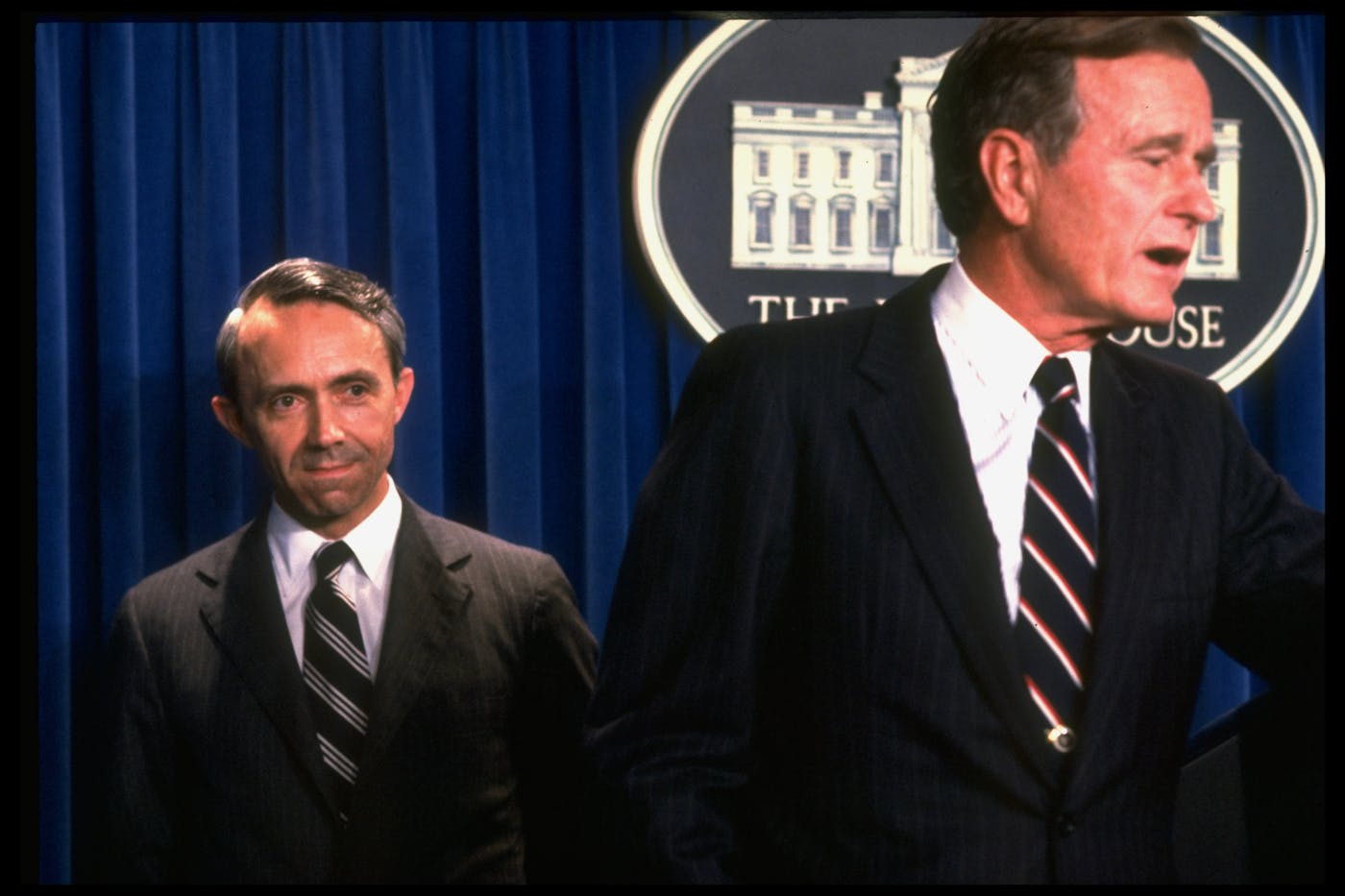

George H.W. Bush nominated Souter to the high court in 1990 expecting him to be a reliable conservative vote. He was, though not in the way that Bush and other legal conservatives expected. Souter’s conservatism was instinctual, not ideological. As the Rehnquist court pushed constitutional law to the right, his preference for judicial restraint led him to drift toward the court’s liberal wing over his 19-year tenure on the high court.

The Constitution, Souter told a class of Harvard graduates in 2010, was not a document that could be read in terms of absolutes or clear meanings but a “pantheon of values” that had to be understood—even if not perfectly shared—by each generation. The constitutional requirement that senators be 30 years old is easy to interpret, he conceded. But most of the text defied the popular understanding that deciding cases was a “straightforward exercise of reading fairly and viewing facts objectively.”

“These are reasons enough to show how egregiously it misses the point to think of judges in constitutional cases as just sitting there reading constitutional phrases fairly and looking at reported facts objectively to produce their judgments,” he explained. “Judges have to choose between the good things that the Constitution approves, and when they do, they have to choose, not on the basis of measurement, but of meaning.”

Souter spent his life as a priest of sorts in the American civic faith, enjoying a semi-ascetic life without a spouse or children. Washington, D.C., with its elbow-rubbing, peacocking social culture, was never a good fit for him. When he retired, he first sought to live in his family farmhouse in Weare, New Hampshire, but had to purchase a new place in a quiet nearby town for a very Souterian reason: The two-story farmhouse could not structurally support the weight of the thousands of books that he owned.

His disdain for D.C. and its politicking eventually extended to the court itself. His most bruising moment came halfway through his tenure, when the Supreme Court effectively decided the result of the 2000 presidential election in Bush v. Gore. In his book The Nine, Jeffrey Toobin recounted how the quiet New Englander experienced something like a crisis of faith over how his colleagues handled the case and considered resigning over it.

“His whole life was being a judge,” Toobin wrote. “He came from a tradition where the independence of the judiciary was the foundation of the rule of law. And Souter believed Bush v. Gore mocked that tradition. His colleagues’ actions were so transparently, so crudely partisan that Souter thought he might not be able to serve with them anymore.” Only at the behest of “a handful of close friends” did he decide against resigning in protest.

Another painful experience came when the court first heard Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission in 2009. The case centered, at least at first, on a documentary about Hillary Clinton during the 2008 election cycle and whether video-on-demand films violated the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act’s restrictions on election spending by nonprofits. As the justices heard the case, however, it transformed into a wide-ranging attack on the constitutionality of federal campaign-finance restrictions.

Souter, by that point, had already announced his retirement from the court at the end of its 2008–2009 term, having barely waited a few months into Barack Obama’s first term before bolting for the door. He was assigned to write the original main dissent in Citizens United, and while it has never been made public, Souter’s draft was reportedly an uncharacteristic barn burner by the mild-mannered departing justice.

“Souter wrote a dissent that aired some of the court’s dirty laundry,” Toobin wrote in a 2012 article on Citizens United for The New Yorker. “By definition, dissents challenge the legal conclusions of the majority, but Souter accused [Chief Justice John Roberts] of violating the court’s own procedures to engineer the result he wanted.” Roberts responded by bouncing the case to be reheard during the court’s 2009–2010 term, thereby putting the constitutional question at the heart of the case—and keeping Souter’s dissent from going public.

It was a symbolically potent finale for Souter’s tenure. His nomination came at a pivotal time in the Supreme Court’s history. After decades of dominance, conservatives did not control the Supreme Court for most of the mid-to-late twentieth century. Franklin D. Roosevelt had appointed all nine sitting justices over his 12-year presidency by the time he died in 1945. Democrats held the White House for all but eight of the next 24 years.

Even Dwight D. Eisenhower’s picks during that two-term gap did not shift the balance: Justice William Brennan became the intellectual leader of the court’s liberal wing, while Eisenhower’s choice for chief justice, California Governor Earl Warren, gave his name to the court’s most progressive era. The Warren court effectively dragged the United States into liberal democracy by ending racial apartheid in the South, adopting the “one person, one vote” principle for redistricting, and incorporating most of the Bill of Rights against the states.

But the river turned after 1968. Richard Nixon managed to appoint four justices in his first term, ending the court’s liberal era and placing its moderates in control. Ronald Reagan’s administration, particularly the Justice Department under Edwin Meese, became a launching pad for many legal conservatives. As the Warren-era liberals died or retired, they hoped to replace them with justices committed to originalism, the conservative legal movement’s preferred method for constitutional interpretation.

Brennan’s retirement in 1990 would be a particularly savory triumph. He had either written or shaped most of the Warren court’s most famous liberal rulings, and he had spent the last two decades dissenting from the court’s turn away from them. Democrats had not nominated a Supreme Court justice to the high court since the 1967 appointment of Thurgood Marshall, who would step aside one year after Brennan.

The nature of Supreme Court nominations had also changed significantly. New Deal liberalism’s political dominance in the 1950s and 1960s had translated into the legal profession. Shifting that tide required immense energy and funding. The conservative legal movement’s initial coalition read like a roster of those who’d lost out in the Warren era: ex-segregationists who opposed further expansions of civil rights laws, cultural conservatives who lamented the end of prayer and Bible study in public schools, tough-on-crime politicians who chafed at broad interpretations of the Fourth Amendment, and corporate leaders who resented unions and regulations.

By 1990, the conservative legal movement was ascendant but not yet dominant. A powerful sign of its limits came three years before Souter’s nomination. Reagan nominated Judge Robert Bork, one of the movement’s intellectual leaders, to fill a vacancy left by a retiring moderate justice in 1987. Bork’s nomination floundered after intense opposition from liberal interest groups and Democratic senators—a break from tradition in an era when Supreme Court nominees regularly received unanimous or near-unanimous approval.

Legal conservatives to this day insist that Bork was unfairly maligned by liberal senators during the process. But Bork’s greatest enemy may have been himself. The outspoken legal scholar had opined on a wide range of constitutional issues over the years: He had denounced Roe v. Wade as “a serious and wholly unjustifiable judicial usurpation of state legislative authority,” rejected the notion that there was a right to privacy in the Constitution, and opposed the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (He later said he had changed his mind on the last one.)

When Brennan announced his retirement in 1990, the George H.W. Bush administration wanted to avoid a similar fate. They sought a conservative jurist who was Bork’s opposite: a minimal paper trail, a scant record of controversial rulings, and a less confrontational demeanor. (Bork’s hairstyle and deep, resonant voice evoked an Old Testament prophet.) They found Souter, who had just begun serving on the First Circuit Court of Appeals after almost a decade on the New Hampshire Supreme Court.

Legal conservatives were uneasy with Souter, especially after he declined to publicly endorse originalism during his confirmation hearing, but their doubts were dismissed by Bush and two close New Hampshire allies, chief of staff (and former New Hampshire governor) John Sununu and Senator Warren Rudman. Souter largely voted with the court’s conservatives during his first few years on the bench but started to drift leftward after he found his footing. His vote to save Roe v. Wade in the 1993 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey proved to be the final breaking point.

The conservative legal movement has an extensive mythology about the judicial wars, to the degree that a judge’s name alone is a potent symbol. To “Bork” someone is to maliciously and unfairly ruin their reputation; perceived apostates from the one true method of constitutional interpretation are deemed to be “Souters.” So great was Souter’s psychological impact on legal conservatives that they restructured their movement to prevent someone like him from happening again. Modern legal conservatism, as I noted in a profile of Justice Amy Coney Barrett earlier this year, is replete with constant ideological checks and socializations of each other to ensure they don’t put any more “Souters” on the bench. The court’s current radicalism is, in many ways, a downstream effect of its failure to double-check that Souter was actually part of their movement.

I do not know how Souter felt about his name being used as a derisive epithet. After his retirement, he made almost no public appearances, aside from serving again on the First Circuit Court of Appeals. (Supreme Court justices are allowed to hear cases in lower appeals courts after they retire, and he apparently relished the opportunity to do so.) I tried to interview him a few times over the years to no avail; his clerks made clear he was done with all that. In an era when the Supreme Court’s conservative majority is inventing “presidential immunity” out of constitutional thin air and clearing the path for insurrectionists to hold public office, I would hope that he took their battle cry of “No More Souters” as a badge of honor.