It takes a few years for new justices to get accustomed to serving on the Supreme Court. Like any new hire to any workplace, the high court’s most junior members tend to take it slow at first. New justices rarely write significant majority opinions or draft thundering dissents. The Supreme Court is like a solar system without a sun, and each new planet must figure out its own orbit carefully.

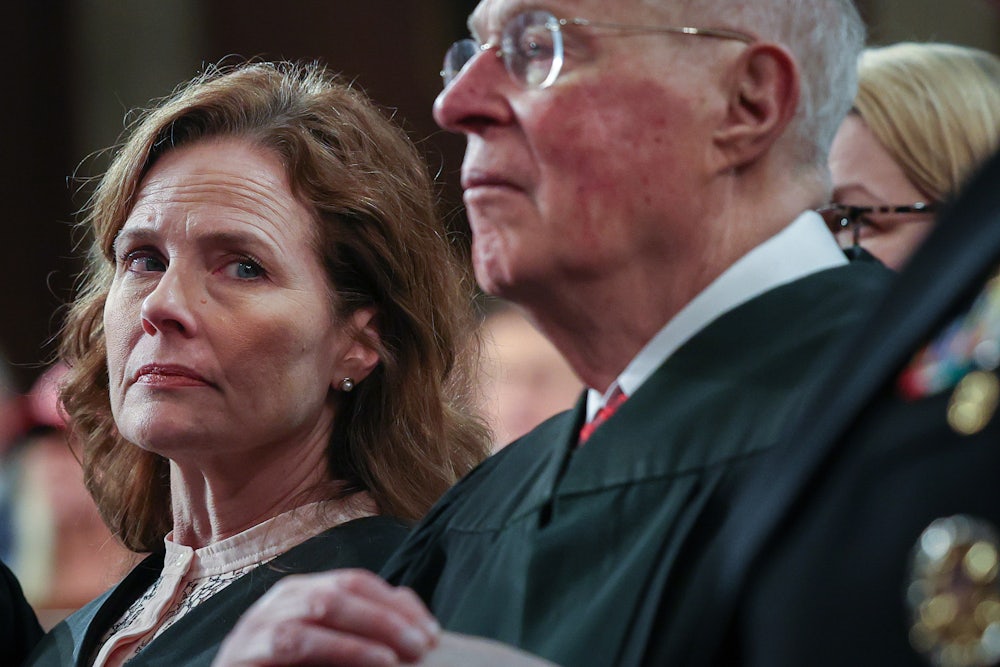

Justice Amy Coney Barrett now seems to have found her own place in this nine-body problem. She remains a reliable conservative vote on the court in major cases. At the same time, Barrett has also shown a sustained willingness to challenge her conservative colleagues over the last year or so, sharply disagreeing with them in some notable cases and voting in dissent with the three liberal justices in a few others.

In last year’s decision on so-called “presidential immunity,” for example, Barrett rejected Chief Justice John Roberts’s sweeping opinion and argued for a more nuanced, case-by-case approach. In an EPA-related case earlier this week, she sharply dissented from Justice Samuel Alito’s majority ruling that the Clean Water Act doesn’t actually require water to be clean. And in the court’s first major decision on the Trump administration’s war on federal agencies, she cast the decisive vote to force USAID to disburse $2 billion in frozen payments for contractors.

The trend is now apparent enough that many conservatives are openly attacking Barrett for perceived disloyalty. Some MAGA activists denounced her in sexist terms by describing her as a “DEI hire.” One conservative lawyer described her as a “rattled law professor with her head up her ass.” Others criticized her for being insufficiently happy to greet President Donald Trump at his Tuesday address at the Capitol.

Josh Blackman, a prominent conservative law professor, even wrote earlier this week that Barrett should resign. In a blog post on Reason magazine’s website, he cited what he described as a lack of “important jurisprudential contributions to the court” in her four-year tenure, as well as his belief that she doesn’t like living in Washington, D.C., and her alleged dislike of Trump, which he inferred from a clip of her during Trump’s joint address.

“With each passing day, Justice Barrett is demonstrating why she had no business being appointed to the Supreme Court,” Blackman wrote. “Indeed, she should have never been put on the ‘short list’ before she decided a single case. And I’m not sure why she leapfrogged over so many other qualified candidates in Indiana for the Seventh Circuit seat. Justice Brett Kavanaugh was described as the most qualified Supreme Court nominee in modern history. Justice Barrett, by that standard, would be the least qualified Supreme Court nominee in modern history.”

His vehemence might seem bizarre to someone outside the conservative legal establishment. But it makes perfect sense within that ideological bubble. Barrett’s writings on the court give the impression of a law professor turned judge who is often exasperated by her fellow conservatives’ shoddy reasoning and corner-cutting. That makes her a problem for a conservative legal establishment that does not expect to ever lose a case again and has prioritized results over rigor.

It would be a mistake to regard Barrett as anything other than a conservative justice. She cast the deciding vote to overturn Roe v. Wade in 2022. She has consistently voted with her conservative colleagues on cases involving religious freedom, capital punishment, and affirmative action. More often than not, Barrett has also joined the conservatives when curbing the power of federal regulatory agencies.

What separates Barrett from her fellow conservatives is how she reached the court. In many ways, her résumé is exactly what the conservative legal establishment looks for from prospective judicial nominees. Barrett clerked for Judge Laurence Silberman, a staunch conservative on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, and then for Justice Antonin Scalia. While working in private practice in the late 1990s and early 2000s, she was one of the many lawyers who worked on the Bush v. Gore litigation for the George W. Bush campaign during the 2000 election. (So did Roberts and Kavanaugh.)

From there, she entered legal academia—first at George Washington University, then at the University of Virginia, and finally at Notre Dame. That path sets her apart from the other five conservatives on the court. She is the only one, for example, who did not work in the executive branch for a Republican president. Justice Clarence Thomas, Alito, and Roberts worked for the Reagan administration; Justice Neil Gorsuch and Kavanaugh worked for the second Bush administration. All but Kavanaugh worked in the Justice Department, a common launchpad for future judicial careers.

Barrett, in other words, avoided the usual stomping grounds for future conservative justices. I’ve written before about how the conservative legal movement is largely structured as an elite social club. It is designed to identify and screen prospective judicial nominees for ideological suitability. Legal conservatives are haunted to this day by George H.W. Bush’s selection of David Souter to fill a key vacancy in 1990. The Bush White House insisted Souter was a reliable conservative when it nominated him. He soon drifted leftward after joining the court, eventually becoming a reliable member of its liberal bloc.

The opportunity cost was immense. Had Bush chosen a more rock-ribbed conservative jurist, Roe v. Wade would have fallen a generation earlier, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992. All of the other 5–4 decisions that moderates like Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy tipped leftward would have probably gone the other way. As a result, legal conservatives redoubled their efforts to ensure that only members of the “club,” so to speak, would be nominated by Republican presidents in the future. When the movement torpedoed Harriet Miers’s nomination to replace O’Connor in 2005, it cemented its control over the process.

As a result, right-wing legal elites spend a great deal of time demonstrating to each other that they are committed to their ideological project. This practice simply does not exist on the left. The difference between the two sides on this point is a structural one, not an inherently ideological one. Liberal lawyers have their own natural social networks as well. But no Supreme Court justice in the modern era has ever drifted from the left to the right, while multiple justices have drifted from the right to the center or the left. Conservative lawyers, in other words, have much more to prove.

How does this screening process work? Legal conservatives meet in the normal course of their work clerking for conservative judges or working for Republican presidents. Friendships and acquaintances naturally form. They then vouch for one another’s ideological bona fides when opportunities for advancement arise. Participating in this process is a credential of its own. Public signs of ideological commitment, especially from the bench, are also valued. Kavanaugh’s writings on the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau were a common touchstone in conservative op-eds and blogs about him during his nomination in 2018; so were Gorsuch’s opinions on the Chevron doctrine when he was nominated the year before.

Barrett largely circumvented that process before her nomination to replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020 because she had already gone through her own ideological trial by fire.

In 2017, Trump nominated her to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. This came as no surprise. By then, Barrett had built a respected academic career at Notre Dame, where she often wrote about originalism and was a member of a campus organization for anti-abortion faculty members. At the same time, Barrett was not on anyone’s shortlist for the Supreme Court before 2017. This is not because of anything she had done; it was simply because the conservative legal establishment generally prefers candidates with judicial experience.

A Democratic senator changed that approach—and, by extension, the ideological trajectory of the Supreme Court itself. Liberal opposition to Barrett’s Seventh Circuit nomination formed along predictable lines. She had previously written about the intersection of faith and the judiciary, including a law review article about how Catholic judges should approach death penalty cases. (Catholic teaching at the time strongly disapproved of capital punishment; it now opposes it in all cases.) Those writings drew heightened scrutiny from Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Illinois Senator Dick Durbin, a fellow Catholic, intensely questioned Barrett over her use of the phrase “orthodox Catholic” in that article. Barrett said it was an inartful choice of words to describe a Catholic judge whose approach to the church’s teachings on capital punishment could lead to conscientious objection. But the most memorable moment came from California Senator Dianne Feinstein, who was concerned about how Barrett’s faith would affect her approach to cases on reproductive rights.

“I think in your case, professor, when you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you, and that’s of concern,” Feinstein told her. Barrett insisted that she would decide cases based on precedent, not her personal religious beliefs. It is hard to overstate how much these exchanges resonated in right-wing legal circles. Conservatives took Feinstein’s comments—and the general tenor of the hearing—as indisputable evidence of liberal and Democratic animus toward Christians in public life.

One National Review writer suggested that the questioning might amount to a “religious test” for judicial nominees, which the Constitution forbids. The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board compared the hearing to McCarthyism with the quip, “Are you now or have you ever been an ‘orthodox Catholic’?” and urged senators to confirm Barrett. “Let’s hope the Senate rejects the bigotry that marred Wednesday’s hearing and approves the eminently qualified Ms. Barrett for the Seventh Circuit,” the board wrote. “The federal bench could use more judges who understand their civic duty as well as Ms. Barrett does.”

As Ginsburg’s health declined during Trump’s first term, Barrett immediately became the conservative legal movement’s preferred nominee to replace her. Her brief tenure on the Seventh Circuit played little role in the calculus. Her appeal to legal conservatives was their perception that she’d successfully owned the libs. Replacing Ginsburg, whom Scalia had once called the “Thurgood Marshall of women’s rights,” with a conservative Catholic mother of seven who had worked on anti-abortion causes would have been satisfying enough for them. That she had also been confirmed to the federal bench despite a religious grilling by Feinstein only heightened their sense of victory.

Barrett did not disappoint her fans in her first few years on the high court. But even during this time, there were subtle signs that she might approach things differently than her conservative colleagues. The first inkling came when the court decided Fulton v. City of Philadelphia in 2021. Philadelphia officials had declined to renew a Catholic adoption agency’s contract with the city, citing its refusal to place children with same-sex couples. The agency sued the city alleging that it had violated the First Amendment’s free exercise clause by terminating the contract based on the agency’s religious beliefs.

Lurking beneath the surface of Fulton was a long-running dispute within the conservative legal movement over the 1990 case Employment Division v. Smith. That case also involved a free exercise clause challenge. The state of Oregon had denied unemployment benefits to two Native Americans for their history of peyote use, even though they said they used it for religious purposes. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the court, ruled that the free exercise clause could not be used to challenge a “neutral law of general applicability” like the Oregon law in question.

The Smith ruling sharply limited the circumstances in which a free exercise clause claim could be brought in federal court. Many legal conservatives, including multiple current members of the court, argued that Scalia’s decision should be reversed in favor of a more expansive interpretation of the clause. Fulton looked like the perfect opportunity to do so: Philadelphia had justified its decision by invoking the city’s anti-discrimination ordinance.

Barrett declined to go that far, however. In a concurring opinion joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, she explained that she sympathized with the plaintiffs’ overall goals and took issue with Smith on what she described as “textual and structural” grounds. “As a matter of text and structure, it is difficult to see why the Free Exercise Clause—lone among the First Amendment freedoms—offers nothing more than protection from discrimination,” she wrote.

At the same time, she rejected the originalist arguments for overturning Smith. Multiple conservative legal scholars and groups had filed friend-of-the-court briefs to offer their view of the historical evidence. Barrett was not persuaded. “While history looms large in this debate, I find the historical record more silent than supportive on the question whether the founding generation understood the First Amendment to require religious exemptions from generally applicable laws in at least some circumstances,” she wrote.

Perhaps more importantly, she rejected the agency’s argument for overturning Smith on pragmatic grounds. The agency and its conservative allies had argued for the court to apply strict scrutiny, an almost invariably fatal legal threshold for the government to meet. Barrett said that she was “skeptical about swapping Smith’s categorical antidiscrimination approach for an equally categorical strict scrutiny regime, particularly when this Court’s resolution of conflicts between generally applicable laws and other First Amendment rights—like speech and assembly—has been much more nuanced.”

Faced with an intra-conservative split on overturning Smith, Roberts’s opinion for the court sided with the agency on more narrow grounds. Barrett’s concurring opinion proved to be decisive: The court has yet to revisit Smith since she cast doubt on finding a workable replacement. Her concurring opinion was also characteristic of her legal background. She sounded like a law professor who found a favorite student’s argument interesting and provocative but ultimately unpersuasive.

Some of her other dissents are grounded in procedural concerns. In a 2021 shadow-docket case involving Covid-19 restrictions in Maine, she argued that the court’s standard for emergency relief, which includes considering whether the requesting party is “likely to succeed on the merits,” should also consider whether the court would grant review on the merits in the first place. She argued this was necessary to ensure that the court would not give a “merits preview” of a case “without benefit of full briefing and oral argument.”

The other conservatives have not embraced her approach, to her apparent frustration. Barrett dissented from an Environmental Protection Agency–related case on ozone pollution last year on multiple grounds, including that the majority was “seizing on a barely briefed” theory to rule against the agency. She closed by emphasizing that the majority’s haste in striking down the EPA rule was an inappropriate way to handle the case.

“Our emergency docket requires us to evaluate quickly the merits of applications without the benefit of full briefing and reasoned lower court opinions,” she noted in her dissent, citing her 2021 opinion on the matter. “Given those limitations, we should proceed all the more cautiously in cases like this one with voluminous, technical records and thorny legal questions.”

Other partings of the ways are grounded in ideological differences. In some cases, Barrett has directly taken her conservative colleagues to task for how they approach conservative legal doctrines. In a First Amendment case involving political trademarks last term, for example, Justice Thomas concluded that the Trademark Office’s restrictions on living names did not violate the First Amendment, citing a long “history and tradition” of allowing them. Barrett sided with Thomas on the outcome, but wrote separately to criticize him for his flawed approach to originalism.

“First, the court’s evidence, consisting of loosely related cases from the late-19th and early-20th centuries, does not establish a historical analogue for the names clause,” she wrote. “Second, the court never explains why hunting for historical forebears on a restriction-by-restriction basis is the right way to analyze the constitutional question.” Barrett also alleged that Thomas did not “fully grapple with countervailing evidence,” a more polite way of saying that he cherry-picked his sources.

Barrett’s dissent in the Clean Water Act case last week also took Alito to task for what she saw as his flawed approach to textualism. She disagreed point by point with how Alito read the statutory text and concluded that his argument “reduces to the broader policy concern that it may be difficult for regulated entities to comply” with the EPA’s restrictions. As I noted earlier this week, that was a polite way of saying that Alito let his personal policy preferences supplant the law that Congress had written.

It should be emphasized that none of these concurring or dissenting opinions appear to stem from any sort of latent progressivism on Barrett’s part. There is no evidence that she is drifting to the left in absolute terms. But she is increasingly finding herself on the opposite side of the court’s conservatives in relative terms. In some of these cases, such as the trademark one, Barrett is criticizing her colleagues on conservative grounds for misapplying their preferred methods of interpretation.

So why is the right so angry with her? Because they don’t want to lose. Barrett’s emphasis on methodological rigor and her aversion to cutting procedural corners would have been lauded by a previous generation of conservative legal thinkers. As things currently stand, that scrupulousness is an impediment to their ideological goals. They expect the six-justice conservative majority to endorse most, if not all, of what they want to do to civil servants, to immigrants, to transgender Americans, to universities, to blue states, and so on.

When Blackman describes Barrett as the “least qualified Supreme Court nominee in modern history,” he is not really talking about her legal scholarship or her judicial experience. He is talking about her participation—or general lack thereof—in the conservative legal movement’s continuous screening for potential Supreme Court nominees who will advance their ideological goals. By those standards, she was indeed unqualified, even though she is a reliable conservative vote in most circumstances.

The easy nutshell metaphor here would be to compare Barrett to a law professor grading her colleagues’ work. I don’t think that is accurate because I don’t get the sense that she thinks she is describing the one, true way to interpret the law and the Constitution to her colleagues in these writings. Instead I get the impression that, after seeing firsthand how the court works, she is slightly aghast at how slipshod it turned out to be.

Ironically, Barrett almost certainly sits on the Supreme Court because of that defining MAGA impulse to humiliate their political opponents. In trying to own the libs by elevating her, however, they deviated from their usual practices and are now paying the price for it. It would be a mistake to describe Barrett as a swing vote, since that usually denotes some sort of ideological moderation. But her willingness to take her fellow conservatives to task for their sloppiness and their shortcuts may be just as influential over the next four years.