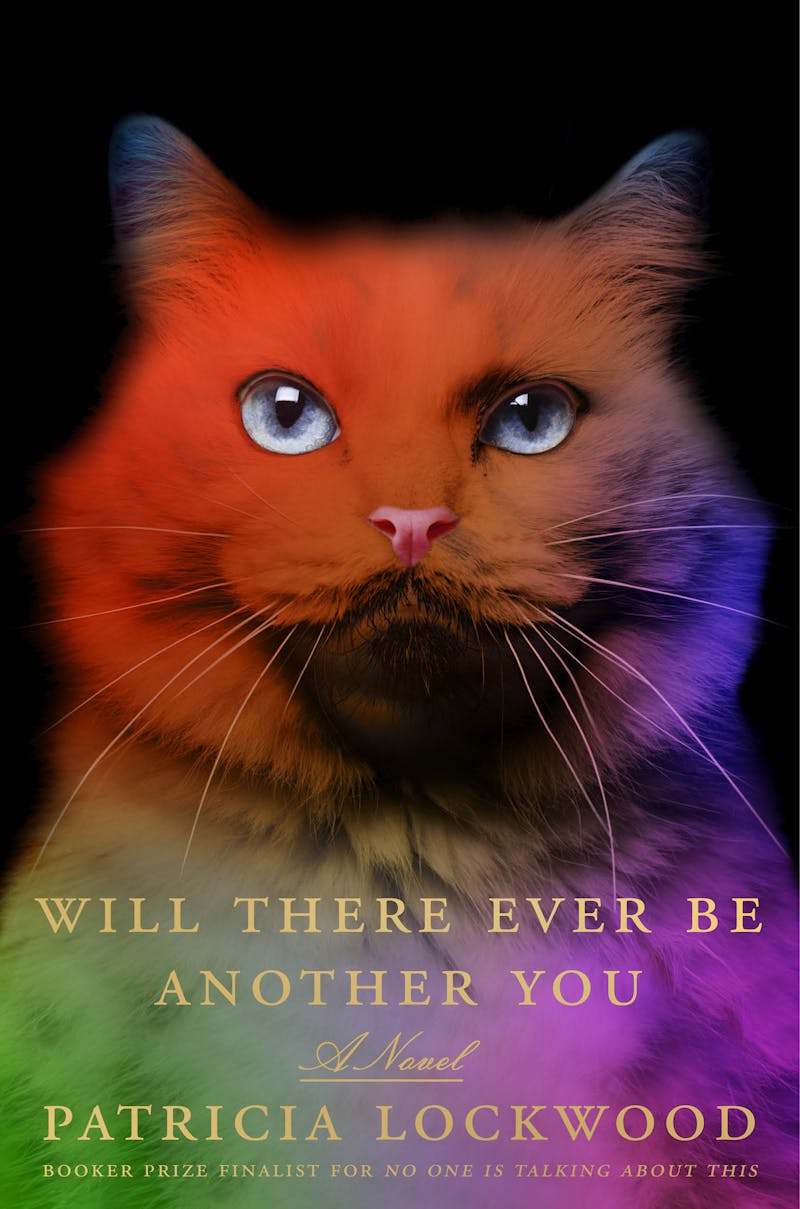

“Twitter est mort,” Patricia Lockwood’s autofictional avatar declares late in her new novel, Will There Ever Be Another You. The declaration is also terminal for the character, who has been gallivanting around Europe during a Covid-addled awards season, and for Lockwood herself, who, like many, has sought refuge on Bluesky.

What will life be like after Twitter? Perhaps it’s too soon to say, but Lockwood attempts to find out in Will There Ever Be Another You, a claustrophobic travelogue of online and IRL adventures abounding with whimsical interludes, all packed taut with her signature wordplay. Deliriums blend together; fellow authors are characters and subjects; subjects and verbs are scrambled; oblique references are made to Outlander and Amazon.com and Property Brothers, a home-improvement show hosted by twins. As Lockwood flies from Paris to Key West to London, she writes a lyrical and barely legible journal of holy and sacrilegious feelings, a pocketbook emptied out in search of the nation’s plot.

How capacious can the novel be? Lockwood asks. Frequently she refuses to fill in the blanks, asking the reader to figure out the punch line. “Something about children,” “Something about the Property Brothers,” “Something about…” “Was that anything?” Always another joke to land; an author, country, or meme to gesture toward. The duality of her writing is a blessing and a curse: “How terrible to be condemned to live life twice, to look on everything as Material.”

All of this to say, there is little plot in Will There Ever Be Another You. This is a book about a person outside of time who takes shrooms while reading Tolstoy and listening to the Beatles. References to macro and micro world events whiz by. But if one has followed Lockwood’s columns in the London Review of Books, one recalls the basic outline. In the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, she fell ill with the virus, endured a monthslong fever, and, in her words, went insane. Not long after, runaway success came her way. She almost won the Booker Prize for her first novel, No One Is Talking About This, and her memoir Priestdaddy was optioned by Amazon before swiftly being canceled. Then her husband, Jason, nearly died from his bowels folding over. Then she met Pope Francis.

None of this is what makes her new book so singular. This is a novel about illness, travel, and death, and the porous nature between fact and fiction. It is a book about the struggle for language, about the snaking of proper nouns from the brain down to the tongue. Memory dilutes language. Each linguistic slip is a chance for Nabokovian adjectives to bloom, for Lockwood’s poetic puzzles to click into place. There is a baroque, biblical quality to her prose. “Open the Song of Songs,” she writes, “and every single like came true.”

No One Is Talking About This recounted the communal experience of the internet, and while the new book does not entirely leave that fertile ground, to it Lockwood adds her deeply individual experience of Covid. Twitter may be mort, but Covid, despite our half-hearted efforts, is not. The virus’s outbreak exposed our fractured society’s woes and made clearer than ever the ways in which social media can amplify both connection and misinformation. Some find like-minded allies, while the pain of isolation leads others to radicalization. Some hone their loneliness like a weapon; it’s easier to dunk on someone than to try to talk to them. For Lockwood, the breakdown of our shared vocabulary isn’t surprising—this has always been her focus, the essential weirdness of the words that pass between us. Her ability to tease out the absurdity of ordinary communication is magnificent, even infuriating.

In her isolation, Lockwood returns to literature with a jaded but persistent curiosity. In her 2020 LRB column “Insane After Coronavirus?,” she discovered she had forgotten how to read after contracting Covid: “I used to be able to do this, I know I used to be able to do this, I will be able to do it again.” At one point in Will There Ever Be Another You she tries to mentor a burgeoning reader. They parse Shakespeare and Walter Benjamin before landing on Joe Brainard, author of the experimental memoir I Remember, where every section begins with that phrase. After removing the “hand job parts” (Brainard’s book is delightfully up-front about gay sex), she finds it a fitting lesson plan to teach the joys of transgressive writing. The distortion of memory, of fact, of the sentence, is her gift.

Lockwood’s stand-in comes from a long line of literal mailmen: “Someone in each generation had to be taught the route.” Perhaps she is a new kind of mailman, a purveyor of the bizarre, poetic (mis)information that glitches in the matrix. Her books are postcards from our very recent past, missives by way of Joy Williams if her family argued about the Property Brothers being persecuted for their faith. In fact, Williams crops up as a character, washing onshore in the epilogue wearing black sunglasses, another pilgrim of Key West. After a night out on the town, Lockwood asks a nearby pair of sunglasses if they are, in fact, Joy. No one ever said the profound can’t indulge in a bit of surreal, slapstick humor.

The first section of the interrogative-filled Will There Ever Be Another You is told in the third person, but by the end of the book we have moved on to Lockwood’s typically zany first person. Metatextual elements abound, references to her previous work in both form and content. Lockwood’s family returns to bungle things up again, this time in ways more tragicomic than cruel. Her father, a converted Roman Catholic priest who once shamed her over her rape, is now interested in conspiracy theories and developing a fully carnivorous diet. Her sister mourns the loss of the child whose brief life was documented in Lockwood’s first novel. The baby’s existence is now solely digital, and the phone that holds those precious photos is almost lost in a fairy pool in Scotland during the opening chapter. Her mother continues to believe in the Christlike quality of a meal at Bob Evans while fussing over her husband’s health. Lockwood’s own spouse, Jason, stoic as ever, becomes enthralled by K-dramas. (“Fandom,” she muses, “must be a way to organize life, longing, and a desire to look things up on the internet—three things that were too large otherwise.”)

Lockwood is now ambivalent about the career that originally took her away from her family. Before turning to novels, she published two volumes of poetry, and she first gained viral fame as the author of the poem “Rape Joke,” published on The Awl in 2013. But the narrator in Will There Ever Be Another You finds it more and more difficult to write in verse. “You stopped writing poetry?” she imagines a doctor asking. “I could no longer bear … the form,” the narrator replies. Perhaps the quippy decontextualized one-liners of X or Twitter have supplanted the impulse toward verses about Nessie and Hypno-Dommes previously found in Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals. Now we have the viral tweet from No One Is Talking About This: “Can a dog be twins?”

This is not to say the fragmentary impulse doesn’t go hand in hand with Lockwood’s cartography of the life of the artist. Context collapse is its own kind of found poetry. Nearly all her books contain a section where narrative fully breaks down into something like a poem. The narrator is replaced by a speaker, one who sees the world passing by through a window darkly. In the new novel, we get the chapter “The Ranking of the Arts,” with cheeky headers like “Film” and “Dance.” Made-up Beatles songs, Sondheim references, and prayers take up the space previously devoted to rhapsodic lines about rape jokes and stigmata. These are Lockwood’s attempts to fill the void, to outrun the deranged anguish of our modern world.

A thread of grief sutures the disparate sections of Will There Ever Be Another You together. Lockwood is reckoning with her illness, her niece’s death, her father’s aging, Jason’s new vulnerability. This compounded sorrow haunts the book—culminating in a chapter called “The Wound.” After Jason collapses in Heathrow and undergoes surgery, Lockwood’s stand-in becomes obsessed with his wound. It looks just like a vagina. They fight over who owns the gash, worried both that it will disappear and that it will always be there, a reminder of life’s fragility. The narrator wonders when she realizes she can put her whole hand inside of him—likening his wound to the side of Christ. Jason starts to worry that he will wake up and there will be blood on the sheet. He asks if this is what getting a period is like. “That’s what it’s like,” she replies. “The big fear is it would happen in church.”

Hospital stays are awful, and to make it through them requires the support of a true believer, someone who visits every day bearing faith that recovery and discharge are just around the corner. This ability to hunker down together is key to Lockwood and her husband’s companionship. “Both of us are easily frightened,” Jason says in Priestdaddy. “It’s why our marriage is so successful.” When something bad happens, Lockwood is quick to turn grief into an action plan. “I’ll write an article! she thought wildly. I’ll blow the whole thing wide open! I’ll ... I’ll ... I’ll post about it!” she gripes in No One Is Talking About This.

The problem is that by the time of Will There Ever Be Another You, no one actually is talking about this. After a few years of lock-in angst and political upheaval, irony dominates the online landscape, and no one is interested in sincere expressions of collective experience. Everyone’s moved on to TikTok. Visual media is king. Lockwood’s wild, earnest pleas go unheard. So she splits the difference, attempting to mimic the voice of the confused masses and to make sense of personal tragedy. All too often, grief is fodder for the discourse. Why try to write an account of suffering when it can more easily be a punch line? Lockwood guns for both. (When Jason wakes up from surgery, he is most worried about misgendering his nurse.) This is a kind of dissociative ethic, one that can’t comprehend horror through empathy alone—not unlike the way autofiction creates a wall of plausible deniability. Sometimes the immensity of the polycrisis also requires a laugh.

For Lockwood, the chaos of lockdown doesn’t just mirror the chaos of falling ill; the two experiences are inseparable. This is beyond hysterical realism—it is the fever dream that has become everyday life. Call it the post-Covid blues. Common sense and sensibility have gone out the window. Driving around, Lockwood encounters endless signs reading: “Pray for America” and urgent pleas for kidney donations. The “purest poster” is a sitting president. Lockwood’s avatar notes that her ability to utilize the internet does not make her special. “Just a fortuitous time to have published a book about the internet being the end of the human mind,” she sighs.

This is a pandemic novel unmarked by the nascent genre’s cliches of privilege and illness as a metaphor. Some recent books—like Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You—have gestured toward the time period in an epilogue, never working through what such world events actually mean for their characters. Sigrid Nunez’s The Vulnerables and Deborah Levy’s August Blue both failed to understand how class mediated their characters’ basically unwounded experiences of Covid. Chronicles of the era can all too easily feel like trauma porn—or worse, pretension masquerading as depth. Everyone became a first responder, ready to cast the blame anywhere collectively but nowhere interpersonally. Such suffering, turned inward, can spiral.

Lockwood, however, manages to explicate the harried, nonsensical, grief-soaked timeline with acrobatic skill. Early on, she recounts wearing, while trying to work, “fingerless gloves and an enormous Looney Tunes shirt … tucking it carefully into her cutoffs so that Speedy Gonzalez did not show.” During her sickness, smiling hallucinations begin to swim around on the ceiling:

She had to cancel plans with friends when it happened and simply wait to die. It was geological. It was grass growing over the forms of the dinosaurs, even the ones that flew … everything had become fine crystal, singing … the roof was gone and she was released up, and up, past mountaintops and sundogs and the zigzagging angel, toward a hole in the atmosphere just her size.

Names and cultural references become untethered from reality. M&Ms feel like an emotion. Cancel culture, Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists, and presidential hopefuls all do battle for relevance, drowned out by the next shiny new crisis. The disembodied connection between language, technology, and illness is clear.

The narrator is also sporting a buzz cut. A hairstyle that “could be dangerous again, that men would slither around you saying boy or girl.” The narrator even wonders if she should change her name, if she might be nonbinary or poly if she’d been born at a later date. The culture wars have always been a topic of concern for Lockwood, but gender in pandemic time takes on a more personal tone. She forgets her name. Patricia no longer sounds right. She instead prefers Dennis. Later, when she discovers a journalist at The Guardian is a TERF, she quips, “wait till she finds out about Dennis.” But Patricia-Dennis’s own ideas around identity are hazy. Are Jason and Dennis swapping normative patriarchal roles?

Lockwood doesn’t seek to answer any of our lingering sex-based questions. A chronicler writes; she does not always unfurl meaning. “I got us here,” Lockwood assures us, “I will get us out.… Do not be afraid.” But one cannot shake the horrible feeling that this is the new normal. “Daily headlines about coronavirus ‘lingering in the penis,’” as Lockwood’s character notes, are small compensation for “the new life” we are “all leading.”

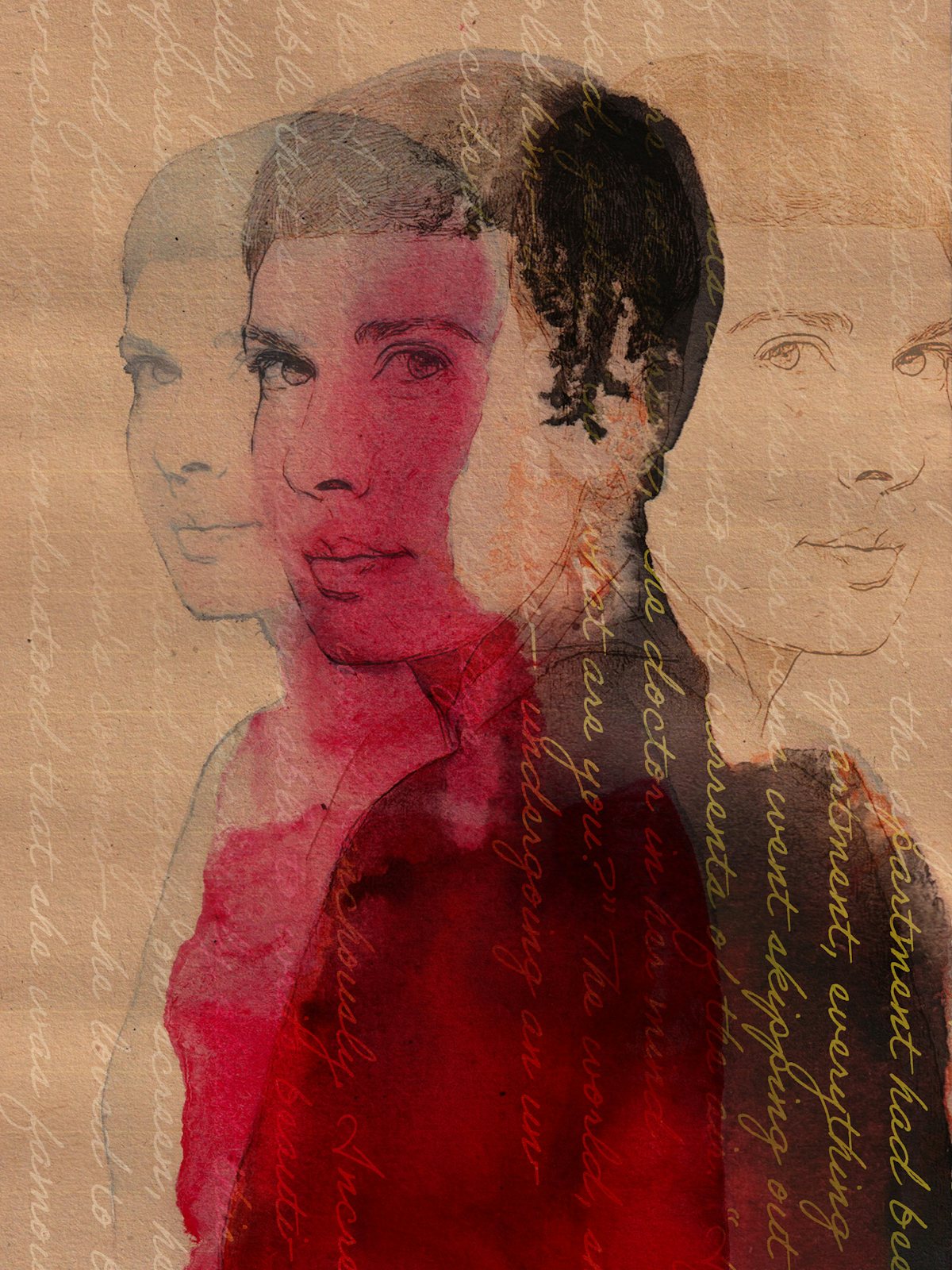

Some experiences, some books, are not meant to be picked apart. They are watercolor gouaches that wash over us as we delight in a palimpsest of colorful impressions. Patricia Lockwood’s body of work is like this: a hymn—or ode, depending on the day—to the painful project of being human. Her pandemic travels offer glimpses of our shared vulnerabilities as “a shoal of fragile colors assembling.”

Will There Ever Be Another You harnesses the power of doubles to remind us of how porous our identities really are, how quickly they can fall apart and come back different. Like a zombie, like a lobotomized doppelgänger. There is Patricia the writer and Patricia the character, Patricia and Dennis, reality and television. The novel begins with an allusion to changelings, children taken and left by mischievous fairies, while the book’s title is taken from an old issue of Time magazine that featured cloned sheep. The uncanny double follows Lockwood throughout her travels, as she struggles to differentiate the real from the shadow, the profound from the mundane. Lockwood hopes to recover from her illness unscathed, but she finds that there is, in fact, another her.

For all its focus on herself, this novel, Lockwood insists, “takes place on the world stage.” Jason’s wound is not just a yonic stand-in, it’s a portal. Tenderness opens us up. Global catastrophe can calcify our isolationism or allow us to take refuge in the breakdown, as, Lockwood reads from Joy Williams’s Florida guidebook, “Fish would use disasters as temporary reefs.” There is a holiness to some moments, she reflects, where one thinks, “After this I will be able to be nice to my mother.” The problem, of course, is that the feeling slithers away. It’s all too easy to become numb to disasters and wounds, to scroll endlessly online and snip at one’s loved ones. But that individualism, like the opposite communal feeling, does not need to last forever. The world stage welcomes us, players one and all, with our entrances and exits. We cannot go back to how things once were. Sans Property Brothers, sans Twitter, sans everything. We will have to settle for reading a book about what it all was like.