Last November, Missouri voters approved a ballot measure guaranteeing paid sick leave to workers in the state and raising the minimum wage, which will reach $15 an hour in 2026. It passed by a solid 58 percent.

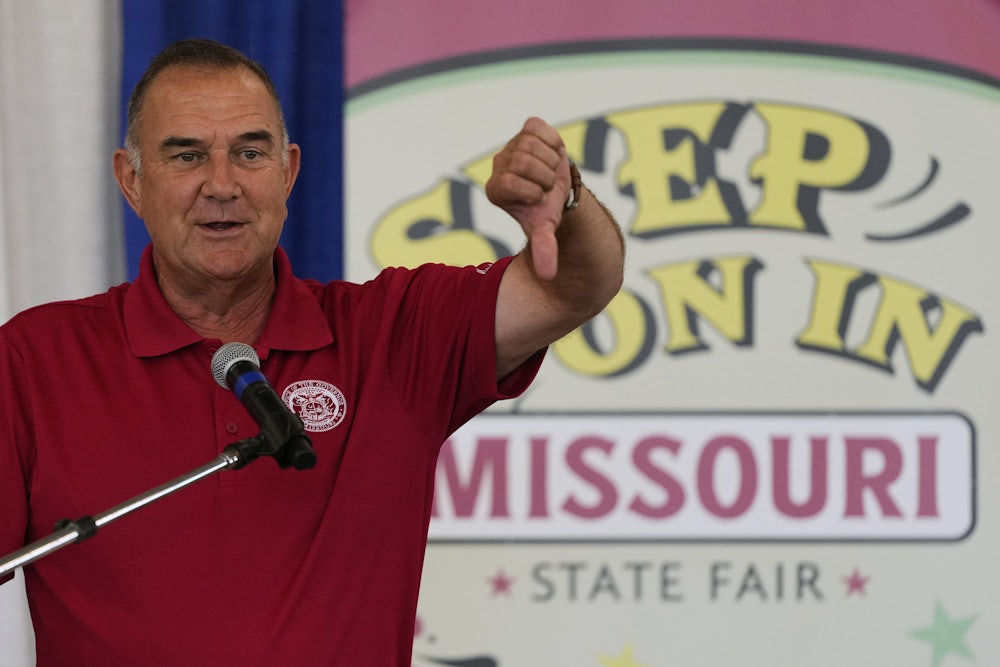

But last month the Missouri legislature, where Republicans have a supermajority in both chambers, overturned the paid sick leave part of the law, as well as a provision that would have continued to automatically increase the minimum wage in the future. “Today, we are protecting the people who make Missouri work—families, job creators, and small business owners—by cutting taxes, rolling back overreach, and eliminating costly mandates,” Republican Governor Mike Kehoe said in a statement. That’s disingenuous, to say the least. They simply disagreed with the majority of voters—and were under pressure from industry groups like the Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry that called the law a “job killer.”

Completely overturning a ballot measure passed by a substantial margin is fairly new and bold, but it’s part of a more recent trend in red states to undermine the will of voters who have passed progressive initiatives at the polls. Increasingly, these approved initiatives are being challenged and weakened by their state legislatures, which may blunt ballot initiatives in general as a progressive policy tool. What happened in Missouri also illustrates the unusual nature of our current state of politics: We’re in the midst of a huge disconnect between what voters want and who they’re voting for to get it. Ballot initiatives make voters feel like they can have it all, choosing policies they like à la carte while voting for candidates based on completely unrelated criteria. It lets legislators off the hook while giving voters a false sense of control. But what’s happening to ballot initiatives in Missouri and other states could be a wake-up call for voters about how they choose candidates.

Twenty-six states allow some kind of ballot referendum process, usually either to amend the state’s constitution or pass new laws, or both. In the recent past, conservative ballot initiatives, like the same-sex marriage ban that passed in California in 2008 (and was overturned by the courts in 2013), were used to drive Republican turnout in an otherwise blue state and try to sway the presidential election. More recently, organizers have focused on passing popular progressive initiatives that legislatures were reluctant to take up, like increasing minimum wages, medical and recreational marijuana legalization, and expanding Medicaid. Many of these measures have proven popular even in majority-Republican states like Arkansas, Florida, Missouri, and Ohio. Last year, Nebraska and Alaska joined Missouri in passing referenda on paid sick leave and the minimum wage.

After the success of those initiatives, states with Republican legislatures hostile to those changes have been trying to find ways to undermine direct democracy. Most often, they pare back statutes so that the laws are less powerful than voters perhaps intended, as Florida has done with felon enfranchisement and gerrymandering initiatives, and Nebraska did with its own paid sick leave law. Other times, states try to revamp the ballot referendum process to make it more difficult to get through. The Arkansas legislature has tried in the past to require a supermajority of 60 percent to pass initiatives, and this year groups in the state are working to enshrine direct democracy rights into the state constitution to prevent more of these efforts. Florida voters passed a ballot initiative requiring a supermajority of 60 percent to amend the constitution in 2006, making a lot of popular changes harder to enact. (Notably, this initiative got 58 percent and wouldn’t have passed under the new rules.)

“We’re in a phase of pushback against the process right now, because the policies have been responding to one direction that the state legislatures have been going for about 15 years, which is in a more conservative direction,” said Craig Burnett, the chair of Political Science at Florida Atlantic University. Responding to the moment may limit conservative lawmakers’ tools in the future, though. “That does swing. You may think this is a good idea today, but you know, tomorrow it may work against you.”

Constitutional amendments are more resilient than new laws passed by referenda because state legislatures can’t tinker with them, and they’ve recently become a battleground over state-level abortion rights. When states try to implement voter-passed statutes, though, the legislatures generally have some authority to decide how they should be implemented, but it’s not always clear what the limits are. Efforts by Republicans to change a referendum that passed in Michigan raising the minimum wage, eliminating the tipped minimum wage, and requiring paid sick leave were overturned by the state’s Supreme Court, and there are questions about how some of those laws will be implemented.

This isn’t always nefarious. Deciding how to implement laws is the job of the legislature, and voters are essentially hiring legislators to do that job for them when they elect candidates. In some cases, asking voters to consider too many referenda, or overly complicated ones, could be seen as shirking their responsibility. In California, for example, voters are asked to weigh in on dozens of initiatives, some of them redundant and counterproductive. Many of these are complicated questions that are better left to legislators.

There’s also a lot of evidence voters don’t always know about the initiatives before they vote on them. That doesn’t mean they don’t realize what they’re voting for—protections like paid sick leave and even longer-term family leave are extremely popular, for example—but they’re not always researching how their elected officials feel about them or what the policies are in their states before Election Day. Practically, that means they might be casting votes in favor of measures while also voting for candidates who wouldn’t support them.

Initiatives also require organized campaigns to collect the signatures and other qualifiers necessary to make it to the ballot, which means the process can be hijacked by millionaires and billionaires who back those campaigns. State officials and campaigns also often wrangle over the language used on the ballot itself, leading to court fights and sometimes to language that is unnecessarily confusing. That can overwhelm voters, turning what is supposed to be direct democracy into another area of politics where big money can distort the process.

Outright repealing popular provisions, however, is new. “Missouri is very pro economic policy, and to see that, it definitely shows that there’s like a new resolve from Republicans to really dismiss the will of the voters and really not care about who they represent,” said Caitlyn Adams, executive director at Missouri Jobs With Justice, which supported the initiative. She said there were some districts where the initiative passed with more votes than the Republican candidates in those districts who later voted to overturn it had. The initiative also had support from small businesses in the state, but the state’s Chamber of Commerce lobbied against it anyway, she said.

Still, ballot initiatives give voters only limited power. Voters approve initiatives they support, but that doesn’t always mean they care enough about the issue they voted for—like paid sick leave—to later vote against a politician who helped to overturn it. Typically, voters have felt more strongly motivated by culture-war issues like abortion than by things like minimum wage laws. Missouri Jobs With Justice is in the early stages of trying to get a constitutional amendment guaranteeing paid sick leave, which would not be vulnerable to legislative tinkering, on the ballot next year. “Ballot initiatives were never a silver bullet,” Adams said. Referencing the Republicans who overturned paid leave, she added, “I think we are going to be spending time telling voters who did this to them; making sure they know who took this away.”

Voters will be impacted by the repeal in varying ways, of course. Many workers already have sick days and paid family leave available from their employers, and since the law had kicked in and some workers were already accruing sick days before its repeal, some businesses may decide to keep the benefits in place. It’s the lowest-paid, most vulnerable workers in the economy who are the least likely to have sick leave and are probably the most vulnerable without laws to enforce. And since the repeal also scrapped a provision that would have protected Missouri workers who actually used their sick leave from being retaliated against, the most vulnerable workers might be unable to actually use any leave they technically have.

We are in the middle of a huge partisan reshuffling. In the past three election cycles, non–college educated voters have shifted to the Republican Party, while the Democratic base, once full of blue-collar and union rank-and-file workers, is now full of college-educated, relatively well-paid white-collar workers. These are workers who already have access to benefits through work, but they are voting for the party with a platform that supports increasing the same benefits for others. At the same time, Republicans seem to have successfully painted Democrats as elite and culturally remote, even while they’re the ones passing tax cuts for the wealthy and generally catering to the whims of business interest groups.

It means that the values that drive people to vote aren’t neatly aligned with personal economic interests—though the degree of this disconnect is still in flux. “We’re not going to be marching to one side of the spectrum and staying there,” Burnett said. “It’s probably more likely to be how it’s been for the last hundreds of years in American politics, which is, we kind of go back and forth, but there is a reasonable expectation that we are going to reshuffle people.” We just don’t know what issue will be the big one that will make that reshuffling settle down a bit, at least until the next major issue upends politics again.

This is the big question hanging over the Democratic Party. For now, however, it’s clear that many of the people who benefited from Biden’s populist economic agenda had no hesitation in voting against him. Adams said future campaigns will also focus on educating voters on candidates who support the initiatives and those who don’t. “We do have to be able to do multiple things at the same time—pass really great statewide policies, and create consequences for elected officials who go against the will of the voters,” Adams said.

But given the Republican assault on ballot initiatives, perhaps it’s also time to educate voters on the problem with depending on these initiatives in the first place. Voters need to decide what policies they want from their political parties—and actually demand them, by choosing candidates accordingly. That remains the surest path to change in this rickety democracy.