On most mornings in the Edward J. Schwartz Federal Building in San Diego, the fourth-floor hallway feels like a gauntlet. Eight immigration courtrooms, their doors spaced evenly along off-white walls, open onto a corridor where masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents lean and wait, arms crossed, boots pressed against the walls—marks of habitual occupation. Immigrants step off the elevator into a narrow passage that can end with a van ride to Otay Mesa Detention Center.

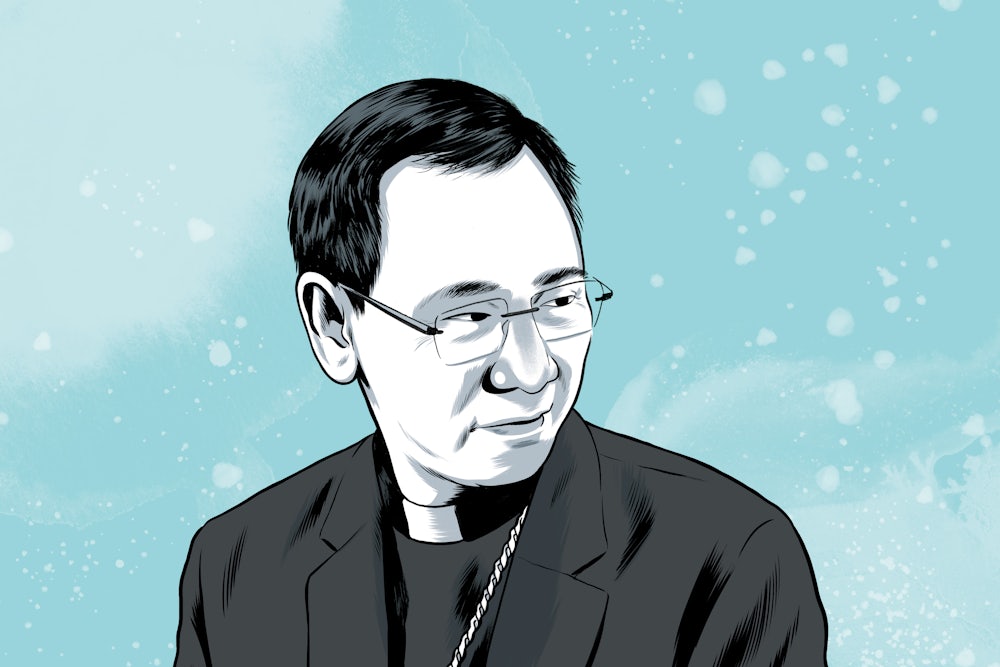

But on June 20, World Refugee Day, the walls still bore the boot marks—and the agents were gone. They had been there, at first, the masks and the posture of authority. Then a delegation appeared: 10 clergy in collars, one in vestments, an imam in a kufi, two Roman Catholic bishops, and one Episcopal bishop—all from California—walking behind Catholic Bishop Michael Pham of San Diego. As they approached, the agents broke apart, one by one, and disappeared.

“Like the story of Moses and Exodus,” said observer Scott Reid of the immigrant-aiding San Diego Organizing Project. “The Red Sea parted.”

Pham moved through the hallway quietly. He let others enter the courtrooms first. He offered nods, not speeches. A government lawyer introduced himself in the men’s room. “He feels conflicted with the situation,” Pham recalled later. “He knows his morals and his values.” On that day, not a single person was detained. Lawyers whispered thanks. Immigrants walked out the front door instead of through the back.

This was the soft launch of the FAITH (Faithful Accompaniment in Trust & Hope) program—an experiment in walking with the downtrodden, as old as the church and as new as this summer. Its premise is as simple as it is subversive: place volunteers in the immigration courts, not to argue the law but to bear witness. More than 50 have signed on so far—clergy and laypeople, Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, Jews. They sign up for shifts: morning, midmorning, afternoon. They sit in courtrooms, stand in hallways, walk with immigrants past the places where agents wait. Their presence changes the equation.

For Pham, the courthouse is not an abstraction. Born in Da Nang in 1967, he was 13 when his parents decided that survival required escape. He, his sister, and his younger brother boarded a boat with 116 others. His parents and five other siblings had been dispersed elsewhere. Three days and four nights without food or water in the South China Sea, then rescue by an oil tanker and a refugee camp in Malaysia. In 1983, a sponsoring family in Minnesota reunited the Phams in Blue Earth, a small town where his father worked as a parish janitor and the children learned English in the public schools.

From Minnesota to San Diego in 1985, from aeronautical engineering at San Diego State University to the seminary, Pham’s life has been a slow accrual of the skills and responsibilities of leadership. Ordained in 1999, he served parishes from Oceanside to Lemon Grove, founded a multicultural Pentecost festival, and, as vicar for ethnic and intercultural affairs, stitched together a diocese that runs the length of California’s border with Mexico. This July, he became its seventh bishop—and the first Vietnamese American to head a U.S. diocese.

He is, by nature, reserved. He prefers listening to talking, small acts to grand gestures. “Bishop Michael is a quiet man who does not toot his own horn,” said Kevin Eckery, his communications director. “But he always steps into the moment.” In the mornings, he works the StairMaster and listens to Spanish-language tapes, determined to speak fluently to the Mexican and Central American Catholics who fill his pews.

Pham does not frame his actions as the result of partisan politics. “Cruelty should never be government policy,” he told me through a spokesman. He affirms the federal right to control the border, but insists that the Constitution’s guarantees of warrants, due process, and dignity are not reserved for citizens. “None of those rights are restricted,” he said. “The Constitution makes it very clear.”

The FAITH program, led day-to-day by a team that includes the Rev. Scott Santarosa, is still finding its form. “We’re trying to make the plane as we fly it,” Santarosa said. But the results, even in the early days, are undeniable. When the clerics appear, the spirit in the hallway changes. “Your presence made a difference,” one lawyer told Santarosa.

On World Refugee Day, before walking to the courthouse, Pham celebrated Mass at St. Joseph Cathedral. In his homily, he told his own refugee story, expressed gratitude to the United States for the chance to start anew, and described the fear of seeing people taken away without reason—first in Vietnam, now in the country that took him in. “We are a human family,” he said. “We stand in solidarity with our refugees, migrants, and immigrants. We are God’s children.”

By midmorning, the hearings had ended. No arrests. In the first-floor lobby, the delegation formed a circle and prayed. Then they walked back out into the San Diego sun, past the idling vans, their side doors still locked.

In the weeks ahead, the FAITH volunteers will return. The boot prints on the walls will remain. But for some who step off the elevator into that hallway, there will also be something else: the sight of a bishop who once arrived in the United States with nothing, standing beside them as they face the machinery of removal.

It is not, in Pham’s telling, an act of defiance. It is a fulfillment of a debt.