From Nuremberg to The Hague, the postwar order promised a universal standard of justice. In practice, it has delivered something else: a system that shields the powerful and their allies, and reserves prosecution for poorer, weaker countries. The same states that helped draft the rules have worked just as hard to ensure that those rules almost never apply to their own leaders. This selective enforcement is not a flaw in the system. It is the system. The case brought last year by South Africa at the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of genocide, a charge co-signed by several other countries, big and small, is only one of the most recent tests of whether the promise of impartial justice can survive geopolitical reality.

The rise of reactionary “anti-globalist” political movements has rendered the possibility of international justice ever more shaky in recent years. During his first term as president, Donald Trump displayed a hostility to the very notion of universal rights. Seeing a ruler’s power as essentially absolute, he extolled Saddam Hussein’s brutal record on counterterrorism in Iraq and celebrated the authoritarian “leadership” of Vladimir Putin. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have warned that the second Trump administration will likely further erode the rights of vulnerable people at home and abroad. The recently constructed Alligator Alcatraz in Florida—a slapdash detention center surrounded by swamps and predatory wildlife—is a brutally surreal symbol of state cruelty.

American politicians have long floated above the reach of global human rights law no matter how egregious their conduct. While U.S. leaders have escaped the scrutiny reserved for the likes of Slobodan Milošević, Charles Taylor, and Laurent Gbagbo, they have also frequently intervened on behalf of friends accused of horrific acts. When the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for the arrest of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu last year, Senator Tom Cotton dismissed the ICC as a “kangaroo court” with no standing to bring charges. “If you help the ICC, we’re going to crush your economy,” Senator Lindsey Graham intoned. Earlier this year, the Trump White House sanctioned the ICC, an act U.N. experts said “strikes at the very heart of the international criminal justice system.”

In a postwar global order defined overwhelmingly by U.S. actors serving U.S. interests, the miracle might be that any world leader friendly with Washington has ever been held liable for their gruesome deeds in an international court of justice. Augusto Pinochet was likely comfortably assured of his impunity when he was awakened in a London hospital by Scotland Yard officials on the evening of October 16, 1998. Two detectives and an interpreter were there to place the 82-year-old retired army general under arrest for crimes committed during the ruthless dictatorship he ran in Chile for almost two decades. “I know the fucker who’s behind this,” Pinochet said. “It’s that communist Garcés, Juan Garcés.”

He was right. As a young man, Garcés had become a friend and adviser to President Salvador Allende, the democratic socialist overthrown on September 11, 1973, in a violent coup led by Pinochet with the Nixon administration’s support. “Someone has to recount what happened here, and only you can do it,” Allende told Garcés on the day he died. Garcés went on to study law in Paris and returned to his native Spain in 1975 after the death of strongman Francisco Franco. Garcés then spent years organizing the legal case against Pinochet under universal jurisdiction, a legal principle allowing prosecution for torture and crimes against humanity regardless of where they occurred or the nationality of the perpetrators and victims. In coordination with human rights groups, he worked closely with a Spanish judge, Baltasar Garzón, who ultimately issued the warrant that led British authorities to detain Pinochet.

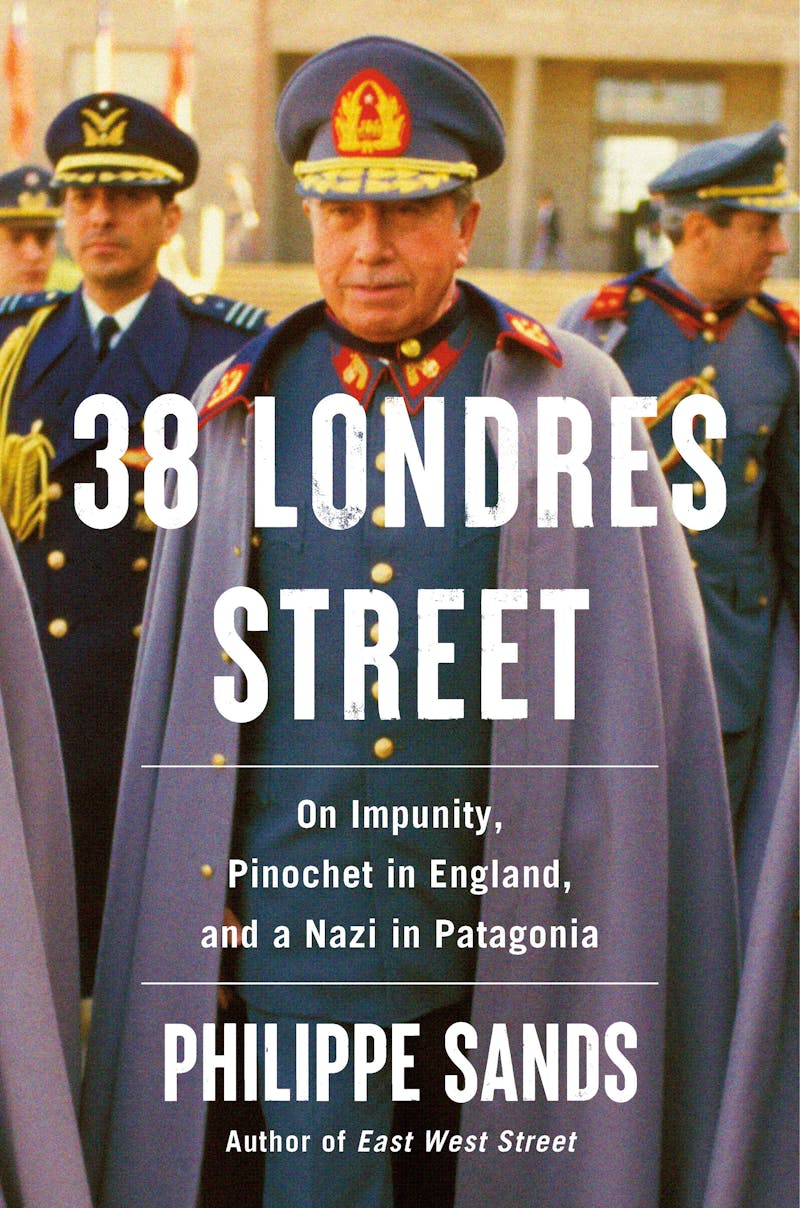

Philippe Sands was an attorney for Human Rights Watch, one of the groups pressing for the prosecution of Pinochet at the time. In 38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England, and a Nazi in Patagonia, he offers more than personal recollections of the case, which he calls “one of the most important international criminal cases since Nuremberg.” As he uncovers the surprising links between Pinochet’s Chile, Franco’s Spain, and the shadowy remnants of the Third Reich on the run, Sands weaves a chilling transnational history of twentieth-century atrocity. What emerges is a profoundly humane examination of the legal, political, and ideological networks that make impunity possible, and a study of the moral clarity needed to confront power when it shields itself behind a uniform, a border, or a flag.

For Garcés, bringing Pinochet to justice was a means of reckoning with the legacies of the Spanish Civil War, fought from 1936 to 1939 between an elected republican government and a fascist military uprising led by Franco. The conflict claimed well over a hundred thousand lives and displaced millions more. As the then–U.S. ambassador to Madrid later recalled, “it was evident to any intelligent observer that the war in Spain was not a civil war.” Something larger and more ominous was afoot: “Here would be staged the dress rehearsal for the totalitarian war on liberty and democracy in Europe.” After Franco’s victory, some 15,000 Spanish Republicans were sent to Nazi concentration camps. Unlike Hitler and Mussolini, the Spanish dictator outlived World War II, serving for decades as a beacon of reaction for authoritarian traditionalists the world over.

As historian Kirsten Weld has shown, crucial figures in the Chilean dictatorship understood themselves to be following in Franco’s footsteps. The Pinochet regime, like Franco’s, sought to impose a conservative, nationalist order that rejected liberal democracy and leftist movements of any kind, justifying brutal measures—including disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial killings—as necessary to preserve order and civilization. Three years after the coup, Pinochet himself told U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger that events in his country represented “a further stage of the same conflict which erupted into the Spanish Civil War.” (Kissinger, for his part, considered Pinochet “a victim of all left‑wing groups around the world.”)

It was in Spain, too, however, that legal activists began the battle to prosecute the Chilean dictator for his crimes. Central to this effort was the case of Antonio Llido, a Spanish priest arrested in Santiago in 1974. Witnesses asserted Llido was badly tortured before he disappeared forever, one of thousands murdered by the state. With the return of democracy in Chile in the 1990s, Chilean and Spanish human rights groups filed complaints on behalf of Llido and other victims, triggering investigations in Spain that culminated in Pinochet’s arrest in London in 1998. The ex-dictator claimed immunity from arrest as a former head of state. But in a highly publicized ruling, the House of Lords—at the time, the United Kingdom’s highest court of appeals—found that former heads of state could not claim immunity for torture charges after 1988, the year that conspiracy to torture outside the United Kingdom became a crime in English law. On other points, however, the decision was mixed, allowing the pro- and anti-immunity sides to claim partial victory. The lords left Pinochet’s fate up to Home Secretary Jack Straw. For a moment, it seemed entirely plausible that Pinochet would be extradited to Spain, where Chilean survivors were preparing to testify against him.

Yet Pinochet never stood trial. Behind the scenes, the ex-dictator’s powerful allies weighed in on his behalf. In 1982, Margaret Thatcher had reportedly given him her word that he could seek medical care in Britain as needed in exchange for support against Argentina during the Falklands War. “During his annual trips to London, Pinochet says, he always sends Thatcher flowers and a box of chocolates, and whenever possible they meet for tea,” journalist Jon Lee Anderson wrote in 1998, just days before Pinochet’s arrest. In the aftermath, Thatcher wrote Prime Minister Tony Blair to lobby for her friend’s release. The Vatican also quietly yet forcefully pleaded for a “humanitarian gesture” from British authorities. For its part, the Chilean government under President Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle—hardly a Pinochet defender—demanded the former strongman’s release in the name of national sovereignty and political reconciliation at home. They all got their way. After 16 months under house arrest in Britain, Pinochet was sent home in March 2000 by Straw. The Spanish case met a dead end.

What makes Sands’s account of this legal drama so compelling is the way he weaves it into both the story of democratic reconstruction in post-dictatorial South America and the broader trajectory of his long-running investigations into atrocity and impunity. Indeed, one way of understanding 38 Londres Street is as the final piece of a Sands trilogy on atrocity and impunity that includes East West Street: On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes Against Humanity” (2016) and The Ratline: The Exalted Life and Mysterious Death of a Nazi Fugitive (2020). Research for both of those works led him to the other major character in this latest book: former SS commander Walther Rauff.

Rauff was born in 1906 in Köthen, a town roughly a hundred miles from Berlin. In 1924, the year Adolf Hitler was imprisoned for leading the Beer Hall Putsch, Rauff joined the German navy. He soon visited South America for the first time, landing in the Chilean port of Valparaíso in late 1925. “Making his way to the Naval Academy,” Sands writes, “Rauff passed the San Rafael Seminary, where one of the pupils was ten-year-old Augusto Pinochet.” This was not the last time the two would be so close.

A dutiful Rauff excelled in the armed forces until he began an extramarital affair that culminated in a nasty divorce and military court proceedings against him in 1937. That same year, he joined the Nazi Party. In 1938, the year of the Munich Agreement and Kristallnacht, Rauff joined the SS, the elite Nazi paramilitary organization led by Heinrich Himmler. Decades later, Rauff’s Chilean grandson would tell Sands he liked to imagine him as a reluctant collaborator. Sands’s careful research shows, however, that Rauff was a true believer. He stood out for his technical prowess and would prove to be an innovator in atrocity. He closely oversaw the design and implementation of mobile gas vans used to murder Jews, Roma, and Soviet civilians in the occupied Eastern territories. “The main issue for me was that the shootings were a considerable burden for the men who were in charge thereof, and this burden was removed through the use of the gas vans,” Rauff later remarked.

In late 1942, Rauff led a special unit in Tunis that persecuted and killed Jews. By September 1943, he was transferred to Italy, where he would meet Mussolini—but not before participating with Karl Wolff, Germany’s military governor of northern Italy, in secret talks with Allied forces, who had landed in Sicily that summer. “In return for peace, he and Wolff hoped to avoid prosecution.” In Switzerland in early 1945, Rauff met Allen Dulles—the powerful local representative of the Office of Strategic Services, the intelligence body that would become the CIA (both the State Department and the CIA have made available troves of documents pertaining to Rauff).

Held in a POW camp after the end of the war, Rauff escaped in December 1946 and spent over a year hiding in an Italian monastery. Like many Nazi fugitives, he fled across the Atlantic. In a letter uncovered by Sands, Rauff advised a former high-ranking SS officer and Nazi official: “Accept the current situation and you can achieve a lot and climb back up the ladder … The main thing is to get out of Europe … and focus on the ‘reassembling of good forces for a later operation.’” Rauff suggested South America.

In early 1950, Rauff and his family arrived in Ecuador, where they set about creating a new life. Rauff engaged in various business dealings and, as was revealed decades later, did some spying for West Germany. His sons took military paths, with support and letters of recommendation from friendly Chilean officials stationed in Quito—including Pinochet, then in his early forties. The future strongman had joined the army in the 1930s, a time when Chile’s military was considered one of the most modern and professional in South America. Pinochet rose steadily through the ranks, holding command positions in various army units. In 1956, he was invited for a teaching stint at Ecuador’s War Academy. “Pinochet and Rauff, and their wives, became socially close, bonded by a virulent anti-communist sentiment, respect of matters German and a mutual interest in Nazidom,” Sands explains, undercutting Pinochet’s later claim of never having met the escaped SS officer with a direct hand in the murder of thousands. The two men saw each other as allies in a shared epic struggle bigger than themselves.

In the late 1950s, Rauff settled in Chile. He joined a large German expatriate community and made an ostensible living as manager of a crab cannery near the country’s southern tip while continuing to write reports for West German intelligence. Accountability eventually came for certain high-profile Nazis in hiding. Adolf Eichmann, who managed many of the logistics of the Holocaust, also fled to South America after the war. He was captured by Israeli agents in Argentina in 1960; taken to Jerusalem to stand trial for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes against the Jewish people; and executed by hanging in June 1962. Rauff himself was apprehended in 1962 in what Sands sees as a parallel with Pinochet: “two men arrested at 11 p.m., on charges of mass murder, with a request for extradition from one country to another.” Rauff assured his family that he was safe, that the high-profile connections he had established in Chile would shield him from Eichmann’s fate. He was right.

Pinochet’s rise to power no doubt set Rauff’s mind at ease. The dictatorship repeatedly rebuffed fresh extradition requests from West Germany and Israel, even as Nazi hunters like Beate Klarsfeld and Simon Wiesenthal located war criminals. For Pinochet, harboring Rauff was neither accident nor oversight. As Sands makes clear, Pinochet’s regime was ideologically aligned with the arch-traditionalism of Francoist Spain and the repressive anti-communist order that Nazi veterans represented. Rauff, an unrepentant party man who celebrated the Führer’s birthday every year, embodied both the continuity of far-right authoritarianism from the 1930s to the Cold War and the conviction that leftist politics were an existential threat to be eradicated.

Sands examines these overlapping life histories and political narratives with sensitivity and clear eyes. He is not inflammatory or accusatory. Rather, through meticulous archival research, interviews, and vivid reporting in several countries, he allows readers to trace surprising—and damning—connections across time and place. Sands himself is often the vessel for these discoveries. He recounts walks in recent years through unassuming Santiago neighborhoods, retracing with torture survivors the footsteps of political detainees and observing the architecture of state violence, unchanged in a Chile that is otherwise vastly different. He visits the site of the former Socialist Party headquarters, turned after the coup into a notorious center of interrogation and torture, at the titular 38 Londres Street. The book includes photos that reflect Sands’s personal, memoiristic style: snapshots of rooms, buildings, and people, evidently taken by the author himself. The effect is to heighten the reader’s sense of accompanying Sands on a chilling journey into a human rights heart of darkness.

When Rauff died peacefully in Santiago in 1984, surrounded by his sons and grandchildren, the Pinochet government had shielded him for more than a decade. His funeral drew open displays of Nazi salutes, a final reminder that the ideological underpinnings of his crimes were far from extinct. In this light, Pinochet’s own confidence in his untouchability seems less like personal hubris and more like the logical conclusion of a system in which those who serve the right cause, in the eyes of powerful patrons, are protected no matter the enormity of their crimes. Just as Rauff eluded the hands of justice, so, too, did Pinochet hope to evade the authority of any court. That he was wrong, even briefly, is why his arrest in London still resonates: It was proof, however fleeting, that the walls built to shelter the powerful can be breached. Pinochet was eventually sent home to Chile rather than Spain, where he would have stood trial. Claiming concerns for his health, he left London in a wheelchair that he abandoned on the tarmac in Santiago. He died in 2006 at the age of 91.

Sands insists that the spectacle of the dictator’s arrest was not for naught. It helped lay the legal groundwork for the successful domestic prosecution of other members of the regime. Unlike Brazil, for example, which never held any agents of its Cold War–era dictatorship criminally liable for human rights violations, Chile made significant legal strides. Over the past two decades, hundreds of military officers have been indicted and dozens convicted for their involvement in forced disappearances and assassinations of dissidents in Chile and beyond.

Chile’s protection of Rauff was of a piece with the regime’s use of former Nazis and fascists as advisers, trainers, and symbols of a militant anti-communist international. It was also a vivid demonstration of the formal and informal mechanisms that sustain impunity—convenient legal loopholes and mutually beneficial alliances binding together fundamentally anti-democratic actors across continents and decades. Our attention to these networks should serve more than historical understanding. Sands, who last year argued against the legality of the Israeli occupation of Palestine at the International Court of Justice, understands this implicitly. In a moment defined by a lack of accountability, the Pinochet precedent reminds us that impunity is not inevitable. It is a political choice that can be—and has sometimes been—reversed.