In normal times, government shutdowns are disasters. Well, in normal times there aren’t government shutdowns at all. But these aren’t even normal abnormal times. While the shutdown that began Wednesday will ultimately impact all Americans—by endangering programs many Americans rely on, and also further eroding faith in our political system—it is actually less bad for working people than the alternative: an open government run by a fascist handmaid of the superrich and his nihilistic enablers in Congress.

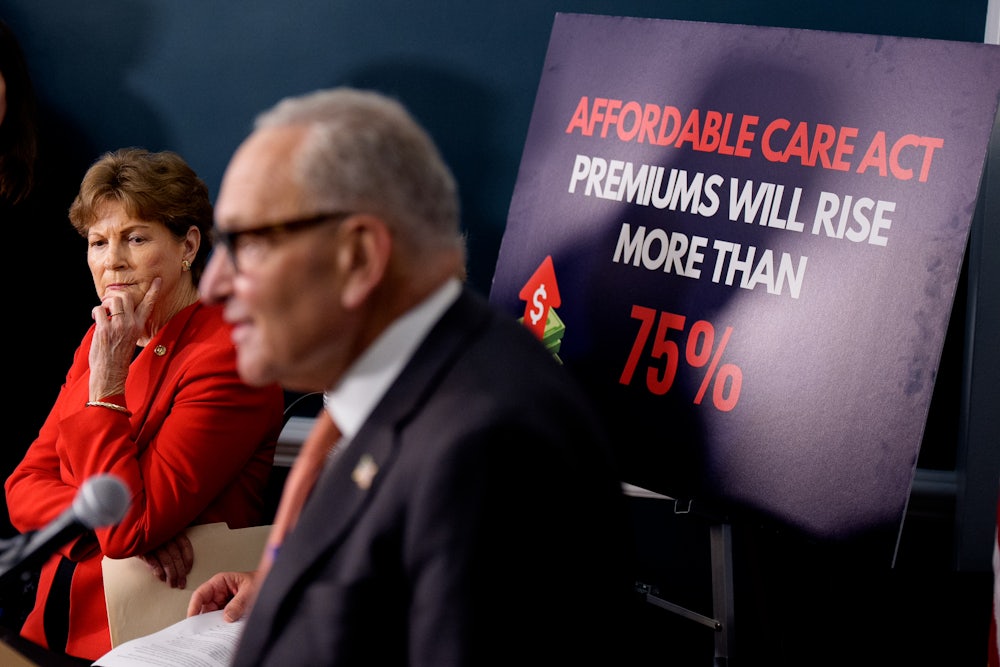

There’s no better example of that than health care, which is the key issue that drove the government into a shutdown. In their spending bill passed earlier this year, Republican lawmakers did not extend the enhanced Affordable Care Act subsidies that were enacted through President Biden’s Covid relief measures. Even though the subsidies don’t expire until the end of the year, Americans will have to enroll in their insurance plans beginning next month, which means that anyone who is already shopping for a plan has seen that their share of monthly premiums will double next year if the subsidies aren’t extended soon. Working- and middle-class Americans who can barely afford their current plans stand to lose insurance unless this is fixed.

Democrats have rightly insisted that any stopgap spending bill to reopen the government must include an extension of the enhanced subsidies. This is a good battle to pick—but also only one battle. If they win this one, and achieve an extension of the enhanced subsidies, maybe it will empower them to fight more of Trump’s agenda. Because what working people need more than anything is a party to fight for them, and neither has done a great job of that in the recent past.

I’ve covered health care as a reporter over the years, but my experience with the health care marketplace is also personal. In 2014, after working at a magazine for almost five years, I became a self-employed freelancer. One of the major factors that made this possible was the ACA marketplaces, which had become fully operational that year. I relied on those insurance plans for the next four years, even as they became more expensive—and then made a risky decision.

The ACA forced the federal government to help cover premiums for families that made less than 400 percent of the federal poverty line, which depended on family size. So for one person in 2014 the income limit was $46,680, and for a family of four it was $95,400—modest, middle-class incomes by any measure. My own income was too high to qualify. I paid a little more than $300 a month my first year to access a reasonably good plan in Virginia. That was affordable on paper, but an expense I struggled with while also paying D.C.-area rent and student loans. As the years passed, my out-of-pocket premium costs rose, and I moved to a rural county in Arkansas, where my insurance plan options were more limited. In 2018, my premiums were more than $400 a month for a plan in which I’d still have to pay out of pocket for a lot of the care I received and faced a fairly high deductible. I was still younger than 40 and relatively healthy, and decided to just skip health insurance the following year and push my luck. I went without insurance until I started working a full-time job again.

This was a common experience. Before the enhanced subsidies, middle-class workers with incomes too high for subsidies struggled to afford their premiums and often opted out. And the costs of premiums don’t take into account other cost-sharing expenses families face obtaining care or buying medicine even when they’re covered.

It’s important to remember that the ACA, though passed by Democrats during the Obama administration, was a conservative law. It established rules to make the insurance market fairer while still fundamentally relying on the for-profit insurance market. Many of the fundamental problems with those markets—like adverse selection, in which healthy people decide to forgo insurance, increasing the costs for people left relying on plans—remained. When the marketplaces launched, insurers raised costs to try to deal with these issues while making a profit. The ACA made insurance much more affordable and fairer than the previous status quo, but ultimately Americans were still burdened with high health care costs and dependent on private insurers who might saddle them with unexpected charges and change their plans every year.

The fact that some of these problems needed to be addressed was obvious in 2019, when more than two dozen Democrats ran for president. The potential reforms ranged from Medicare for All, which Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren supported, to the incremental improvements proposed by Joe Biden, who proposed improving the ACA. Once in office, the Biden administration tried to do that. In 2021, new rules prohibited insurers from charging customers surprise out-of-network expenses when they were hospitalized in-network but couldn’t choose their own doctors, a problem that had previously cost insured people tens of thousands of dollars. The enhanced subsidies were established in the American Rescue Plan in 2021, when Congress increased the amount of the subsidies available to people who qualified for them and also raised the income cutoffs so that more people qualified. The subsidies were extended to the end of this year in the Inflation Reduction Act.

The subsidies addressed long-brewing trouble with the marketplaces, and they worked to increase enrollment. “It contributed to the marketplaces doubling in size,” said Cynthia Cox, vice president and director of the Program on the ACA at KFF, a nonprofit health policy research, polling, and news organization. “There’s no other change that could explain that growth.”

So it’s no surprise that Democrats want to make them permanent (or, at least, extend them again). Without them, costs will soar for families who rely on the marketplaces to buy their own coverage. Many customers will drop out, leaving coverage pools sicker in general, which will likely increase costs even more down the road. It’s a vicious cycle that puts the entire ACA system at risk.

Republicans may be happy about that, since they’ve been trying to abolish or weaken the ACA for the last 15 years. But Americans are used to its protections, and however faulty the marketplaces are, they’re vastly superior to what came before, when many self-employed Americans simply could not buy insurance at all. More than that, Americans are used to the ACA and don’t want to get rid of it. In fact they want to make it better, and generally trust Democrats on health care more than they trust Republicans.

Democrats have a little time to negotiate with Republicans before many Americans feel the pain of a shutdown. While some parts of the federal government, like paychecks for many federal workers and application processing for various loans, stopped immediately Wednesday after funding expired at midnight, many programs that lower- and working-class people rely on are funded in advance. Social Security and Medicare are mandatory spending programs, which means they remain unaffected, and other programs like nutrition assistance and Head Start are funded in advance, so most of the Americans who rely on them won’t see changes unless the shutdown drags on for more than a week or longer.

But even when Trump’s government is operational, his actions—decimating the federal workforce, raising tariffs on imports, widespread immigration detention and deportation—have already smashed the fragile security many working-class Americans relied on. That’s likely to get even worse next year and the year after, when key measures in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act go into effect, like work requirements that will knock more Americans off Medicaid.

If Democrats succeed in extending the enhanced subsidies in this round of negotiations, they will save some families from losing health insurance in the next few months, but working-class families will still face a mountain of problems. What they need are politicians willing to stand up to a Republican Party that promised to help working-class voters but instead passed tax cuts for billionaires. If ever there were a time for Democrats to win back some of those voters, this is it.