Among those who turn to the Affordable Care Act marketplace to purchase health insurance, many depend on enhanced subsidies to ultimately obtain coverage. But those all-important tax credits are currently set to expire at the end of the year. That means out-of-pocket health care costs are expected to skyrocket for millions of Americans. Congress could swerve to avoid this cliff, as there is a limited period of time to extend these tax credits. But despite their popularity, political dynamics may well leave low- and middle-income people in the lurch.

Enrollees are already expected to face sticker shock, with insurers participating in the ACA marketplace proposing an 18 percent premium increase in 2026—11 percentage points higher than last year. But on top of these rising costs, the expiration of the enhanced credits would result in out-of-pocket premiums spiking by an average of more than 75 percent.

“If the enhancements expire at the end of the year, it would cause a lot of disruption in the marketplace, a lot of disruption in people’s lives,” said Claire Heyison, senior analyst for health insurance and marketplace policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “In some states, particularly states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, they could see like half of their marketplace enrollees exit the marketplace, which is really disastrous for both marketplace enrollees and for the ACA marketplaces.”

Since the enhanced subsidies were implemented, dramatically reducing premium payments, ACA marketplace enrollment has reached record highs. In 2024, more than 21 million Americans were enrolled in the marketplace, nearly double the number of enrollees in 2020. That number increased to more than 24 million people in 2025, according to KFF. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, roughly 93 percent of people who receive insurance through the ACA marketplace receive the enhanced subsidies, saving them an average of around $700 in 2024.

Even before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, then–presidential candidate Joe Biden had campaigned on expanding the Affordable Care Act subsidies. At the time, tax credits to lower premiums were only available to people making between 100 to 400 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2021, the Democratic-led Congress approved temporary subsidies as part of the American Rescue Plan, the massive coronavirus relief package that expanded several social benefit programs. This law made the premium tax credits available to people earning above 400 percent of the federal poverty level, and made them more generous across the board. The following year, the Inflation Reduction Act extended these enhanced subsidies through the end of 2025.

The surge in enrollment was particularly notable in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA; non-expansion states saw a 152 percent increase in ACA marketplace enrollment between 2020 and 2024, according to KFF, as compared to a 47 percent increase in states that have expanded Medicaid coverage. This coincided with the expiration of other pandemic-related policies, such as automatic reenrollment. As people lost their Medicaid coverage in the wake of this change, the enhanced subsidies made it easier for them to enroll in the ACA marketplace.

It will be a different world should these benefits expire. Without the enhanced subsidies, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office has estimated that marketplace enrollment would drop dramatically, predicting that only around 15 million people would be enrolled by 2030. The CBO has also predicted that more than four million people could lose their insurance by 2034 thanks to the expiration of the enhanced subsidies.

A family of four that earns $150,000, for example, would lose subsidies altogether, which would mean that they would go from paying around 8 percent of their income to roughly 20 or 30 percent, said Cynthia Cox, vice president and director of the Program on the ACA at KFF. So they might decide to drop health insurance—and insurance companies, predicting this eventuality, are already hiking premiums in advance.

“Insurers know that that coverage is going to be less affordable next year for a lot of people, and that might mean that healthier people drop out of the market, so they’re left with fewer enrollees who, on average, are sicker,” said Cox. “So that causes premium average costs to go up—and then premiums go up in response.”

Other households currently earning up to 150 percent of the federal poverty level are able to obtain plans with no premiums. Before these subsidies were available, these Americans had to pay about 2 to 4 percent of their annual income for a plan with a reduced deductible.

“It was a considerable increase in affordability,” said Matt Buettgens, senior fellow at the health policy division at the Urban Institute. “Two percent of income for someone of that [poverty] level is not trivial.”

The expiration of the subsidies is not occurring in a vacuum but within the context of dramatic recent actions by Congress. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, President Donald Trump’s massive legislation extending tax breaks and slashing government spending, made significant changes to the ACA, including limiting the enrollment period, eliminating automatic reenrollment for participants, and making it more difficult for lawfully present immigrants to enroll in marketplace coverage. The CBO has estimated that the changes to the ACA included in this legislation would increase the number of people without health insurance by more than two million by 2034.

“Taken together, these actions are making marketplace coverage more expensive. They’re limiting eligibility, and they’re adding paperwork requirements or making it more difficult for people to stay covered, or get coverage in the first place,” said Heyison. “It’s really kind of an attack on the marketplace from all different angles.”

However, Robert Kaestner, an economist at the University of Chicago, argued that people who lost health care coverage due to the expiration of these subsidies might be able to obtain insurance through other means. “These policies, while potentially dramatic, really end up having much smaller consequences than the partisan debate suggests,” he said.

Kaestner pointed to census data released this week that showed that fewer people were enrolled in Medicaid in 2024 as compared to 2023, in part because of the end of automatic reenrollment. However, there was no dramatic change in the number of Americans insured overall, which Kaestner said showed that people were obtaining health care through other means. The census data also showed that the percentage of people insured through private insurance increased by 0.7 percent between 2023 and 2024.

“There could be some group that won’t be able to offset the loss of private insurance with Medicaid or the marketplace, particularly that group in the 250 to 400 percent of poverty range that won’t be getting the subsidies they were getting—they might find a little more difficulty,” Kaestner said. “This is a small group. Most people with 250 percent to 400 percent of poverty income have private insurance.”

However, new analysis by KFF found that nearly half of all adults under age 65 enrolled through the ACA marketplace are employed by a small business with fewer than 25 workers, are self-employed, or are small-business owners. Small businesses are far less likely to offer health insurance for employees than large companies. Cox said that people could potentially choose to limit their income to ensure that they still have access to the ACA marketplace, or to lower premiums.

“For someone who’s really close to that income cutoff … maybe that means working fewer shifts, or just selling fewer items on Etsy or whatever it might be, or not giving as many Uber rides,” said Cox.

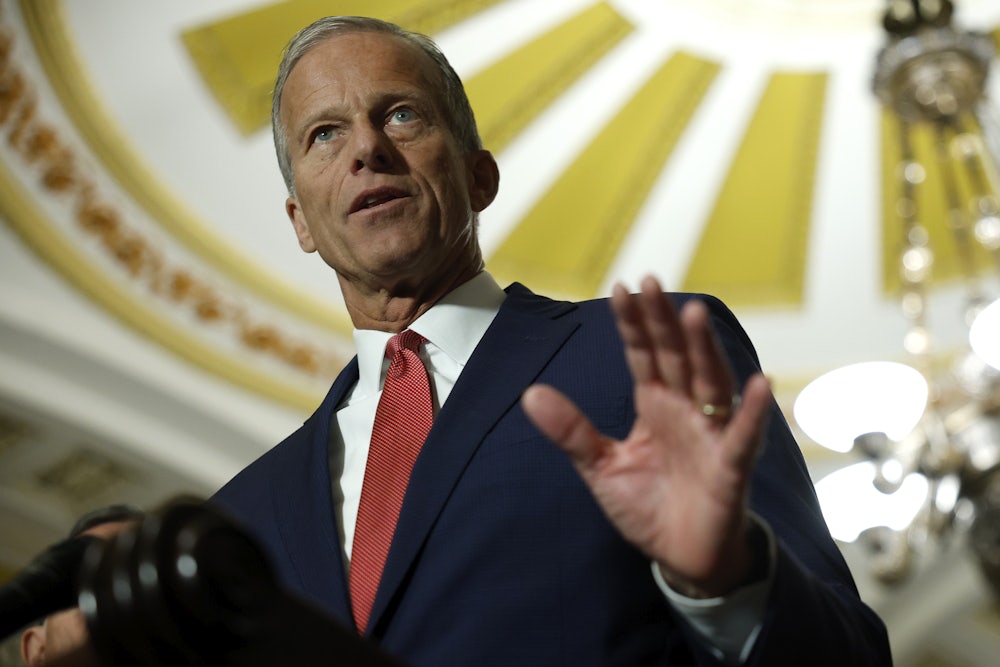

It’s unclear whether Congress will take any action to extend the credits. Earlier this month, a group of vulnerable House Republicans joined moderate Democrats in introducing legislation to extend the subsidies for one year—beyond the midterm elections. With government funding set to expire at the end of this month, Democrats are seeking potential concessions to earn their vote to keep it running, including potentially extending the tax credits, although they have made no formal demands. But Republican leadership seems largely uninterested, with Senate Majority Leader John Thune saying on Tuesday that he wants to pass a “clean” continuing resolution to keep the government running. Republicans have also pointed to the cost of extending the subsidies, which would be around $30 billion per year.

Republican strategists have identified the looming expiration as a potential liability for swing-district Republicans in the midterm elections. Trump campaign pollster Tony Fabrizio co-authored a memo with Bob Ward in July warning that “unlike recent changes to Medicaid which do not go into effect until after the midterm elections, voters on the individual insurance marketplace, who voted for Trump by 4 points, will begin getting notices of significant premium hikes this fall.”

“Republicans can expect a loss of support in these most competitive districts if the premium tax credit is not extended,” the memo said. This sentiment was echoed in an August op-ed by another Trump pollster, John McLaughlin, who argued that Republicans would “risk significant political consequences” if they did not extend the enhanced subsidies. According to McLaughlin’s polling, 83 percent of voters supported preserving the tax credits.

“Not only do the numbers indicate that the vast majority of Americans support extension, they also make it clear that preserving these critical tax credits is a political winner for Republican lawmakers ahead of the 2026 midterm elections,” McLaughlin wrote.

The Trump administration appears to somewhat recognize the political urgency of the situation; the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced last week that it would make catastrophic health insurance plans available to those who don’t qualify for premium tax credits starting next year. However, while these health plans—intended to assist during emergencies—have low premiums, they have high deductibles that would not necessarily mitigate the out-of-pocket costs. (Meanwhile, a new rule proposed by the administration intending to crack down on what the administration calls improper enrollment in the ACA was blocked in court last month.)

And while the expiration of these premium tax credits won’t occur until the end of the year, many Americans will get a dose of sticker shock long before 2026 rolls around. If Congress does not act before November 1, which is when ACA enrollment opens, people will get an early look at the effect of higher premiums and the expiration of the subsidies. Recent KFF polling found that nearly 60 percent of people who purchase their own insurance plans—most of which are ACA marketplace plans—have heard little to nothing about the looming end of the tax credits.

“People might believe, understandably, that this is happening because of a decision that their insurance company made. And while that’s the case—insurance companies are making decisions based on the political environment—it’s really Congress that’s ultimately responsible for that environment,” said Heyison.

Some Republicans argue that the enhanced subsidies were intended to be temporary because they were initially enacted in response to the coronavirus pandemic, and thus they are no longer needed. “[Democrats] could have written it to last forever. They didn’t. They wrote it to expire this year. So we should just let it expire,” Representative Andy Harris, the chair of the House Freedom Caucus, told Semafor.

However, given Biden’s initial campaign promises on expanding access to the ACA and the extension of the credits in 2022, it seems apparent that Democrats’ intentions, at least, were to make the subsidies permanent. Buettgens noted that, regardless of the initial political intentions behind the passage of these credits, the end result for losing them is clear.

“These people don’t suddenly have affordable health care options that they didn’t have before,” said Buettgens. “There’s obviously a demand for this, and there will not be a similarly affordable option without it.”