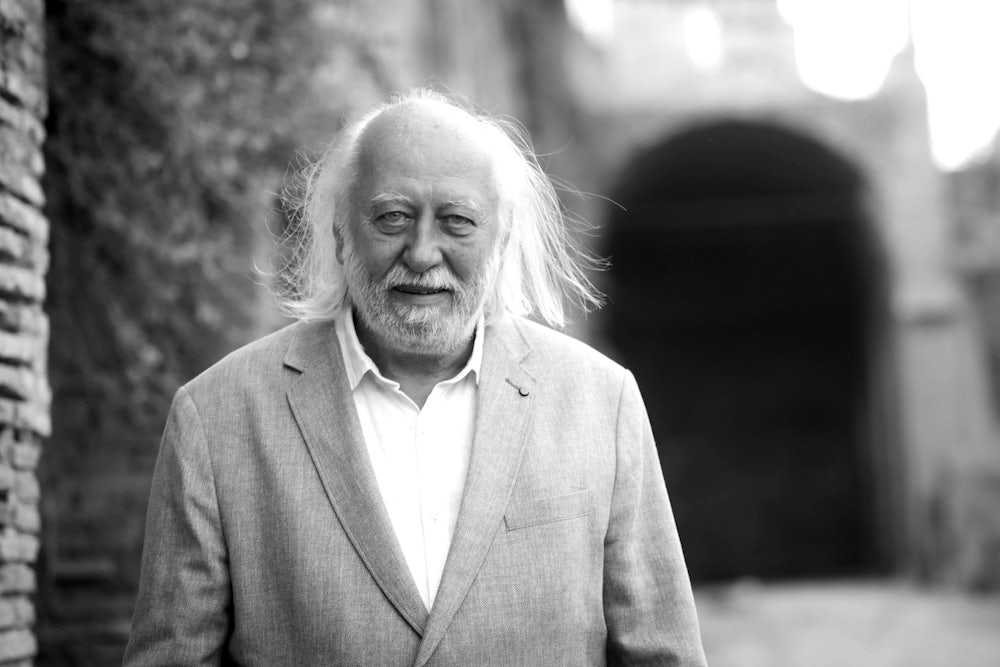

As soon as László Krasznahorkai won the Nobel Prize in literature, I started getting congratulatory texts. Not because I have played any role in the Hungarian author’s success but because for years I have attempted, mostly unsuccessfully, to convert friends to his intricate charms. I keep a copy of Seiobo There Below next to my bed as a source of emergency bedtime balm; I have pictures of its three-pages-long first sentence in an email that I send to seemingly persuadable readers. I first read Krasznahorkai by accident, frozen in a bookstore and vulnerable to the holograph on Seiobo’s cover. As befits the cascading form of his novels and the fanatics among his characters, one book led to another and another and another. Except for those still only in Hungarian and the novella Animalinside (of which only 2,000 copies were printed, each costing $300), I have read every one of his books. I’ve wanted to write about him for years: about his style, his themes, his lonely acolytes. But until now, no one has been too interested.

Krasznahorkai’s following is small but extraordinarily devoted; his most loyal readers have a tendency to fall into frenzied, minutely detailed conversation about his writing. Its complexity has aggravated some and deterred many. Critics tend to describe Krasznahorkai’s style, with his long sentences—Herscht 07769 is technically one sentence—as hypnotic or mesmerizing. His layered digressions are called unsettling, his novels likened to an abyss. There is no doubt that reading him can be challenging. Two hundred and eight pages into the sentence that comprises Herscht, for instance, presents:

… it comprised a much more abundant wholeness, itself only apprehended by means of another viewpoint, radically differing from the conventions of science, although not unscientific or antiscientific, not some kind of mystical or transcendent or other foolish gobbledygook, but instead an image of the real obtained via a different view, only that the construction of this reality, its logic, is not yet before us, because we cannot know, here, what exists there in place of a causal system, and this is what he wished to say: the decisions of the Security Council must emphasize the fully justified concern over the catastrophe that might ensue at any moment, and yet as we stand in the dreadful shadow of this total catastrophe, we must yet realize: the experiential world as sensed by ourselves, from the viewpoint of this veritable realm, is only an idea, a mere idea, Mrs. Chancellor, of what reality truly is …

To pick a fairly mild example. In my experience, however, reading Krasznahorkai is challenging not because it is unwieldy and frenetic but because it is meticulously, precisely, intricately ordered. Antecedents are answered by consequents, clauses that are left open find closure, chains of thought eventually relink—even if we must track them over pages. We are not used to this task. For me, reading his sentences, following the subtleties in his worlds, serves as a dose of rare and cleansing concentration. It is a visceral experience of feeling one’s brain struggling with, but ultimately embracing, a mental mode far different from the one conditioned by emails and group chats, social media, and screen time. It doesn’t feel like getting lost: It feels like finding oneself precisely coordinated, grounded in a mass of text. It is a pure antidote to the worst cognitive tendencies in the rest of our lives.

Consider “He Rises at Dawn,” one of my favorite chapters in Seiobo There Below, a book described as a novel but which will read for most as an anthology of stories about art and creation. One of many works that engages Krasznahorkai’s interest in Japanese craft and culture (those with similar interests should try the novella “A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East”), this chapter is about an expert mask maker working on a single mask. He works

a month and a half, so, roughly, that much time, here on the tatami placed in his work-box from early morning to early evening, and as for speaking, he doesn’t speak, not even to himself; if he makes any sounds at all, it’s only that he is lifting the piece of wood and quietly blowing off the wood shavings chiseled off the mask, and sometimes when he changes his physical position in the work-box and sighs while doing so, and once again he bends toward the block of wood, for at first it all begins with the Okari wood-merchant located in the one-time Imperial Palace, below Gosho to the south, in the person of Okari-san, who is of about the same stature as he, therefore very short, a good fifteen years older, and fairly gloomy, Okari-san, from whom he has been buying wood for years—he just bought this newer piece—he trusts him, the price is always good, the annual rings are thick and dense, the lines are without defects, namely the hinoki from which the chosen block of wood originates grew slowly; in addition, the wood is delivered from Bishu, in the prefecture of Gifu, from a forest that has the highest reputation, from a forest renowned for the quality of its material—the whole thing is a simple rectangular-shaped block of wood, that is how it all begins, with the circular cutting with the saw on the basis of the stencil to the desired proportions; he does not think, because he doesn’t have to, his hand moves by its own accord, he does not have to control its direction, the saw and the chisels know by themselves what they have to do, so it is no wonder that this first, this very first phase of the work is the fastest, the most free from the later, frequently tormenting anxiety …

Roughly the same plot of this story could be covered in a “Come With Me as I Make a Japanese Noh Mask” Instagram reel, from the montage of the idyllic woods to the time-lapse of a wood block shaving into shape. The vast majority of our media consumption and communication is now defined by this compression of complicated, unwieldy life into tidy little rectangles. Social media videos, television, and films are designed to demand the smallest of sustained attention, and to capture it as quickly as possible, as part of a larger project of sustained attentional extraction. TikTok is the apotheosis of this trend: To prevent the viewer switching to other content, the content will continually switch for the viewer. That infinite carnival, I think we all can recognize, is the real hypnosis, the true abyss.

In contrast, any time I sit down to read Krasznahorkai, it feels like launching into space: a terrible roar, a series of bumps and shakes, and, mostly, an irrepressible forward motion that eventually sustains itself. If I’ve spent hours or days flitting about threads and feeds, the initial resistance can be intense. He rejects the smoothness, synopsis, and universal flavor of our modern digital culture. Our mask maker is a very specific one, in a very specific space, found at a very specific time. In another of my favorite chapters from Seiobo There Below, “Il Ritorno in Perugia,” Krasznahorkai spends nine pages describing the exact steps a fifteenth-century workshop takes to prepare a canvas so that its maestro may paint.

But his heterodox style or esoteric subjects don’t ultimately make for fitful or circular reading. It’s all headed somewhere, and sometimes it’s headed there fast. Krasznahorkai will kill off a character amid a bush of commas, barely noting their demise as he gets on with, say, the cataloging of a desk’s items. You can’t look away because you can’t afford to. War & War and The Melancholy of Resistance both offer stretches of Krasznahorkai at his most propulsive, aided by plot where characters themselves are flowing forward, rather than solely considering existential puzzles in decrepit hovels. A spirit of a chase, in the latter novel, is described with this sentence:

The bitter, evil pleasure of seeing these three lonely shadows helplessly swaying ahead of us, not even knowing for certain what was in store for them, exceeded even the power of the spell cast by the sight of the smashed-up town, meant more than the satisfaction occasioned by all the pieces of useless stuff we had trampled underfoot, for in that perpetual holding back, in the sheer joy of deferral, in that infernal putting off, we savoured something wry, mysterious and ancient that lent our least movement a fearsome dignity, the kind of unimpeachable pride possessed by all barbaric hordes, even when they know they might be scattered far and wide the day after, mobs whose momentum is unstoppable since they have appropriated even the thought of their own death, should they decide to make an end, their mission done, having had their fill for ever of both earth and heaven, with misfortune and sadness, with pride and fear, as well as with that base, tempting burden which will not allow one to give up the habit of pining for liberty.

Part of the challenge of selling Krasznahorkai beyond a Nobel jury is that his work is not compellingly summarized nor easily excerpted (see: this essay). He resists the passive absorption that we’re accustomed to. Instead, you might consider his texts as a building. Viewed up close, we see a variety of mundane materials pressed together; given a longer view, a grand architecture emerges.

Not just for this reason, brevity is not a sign of accessibility in Krasznahorkai’s works. It’s actually his longer novels that offer more traditional footholds for fiction readers. Although Herscht is written as one long sentence, it offers the most recognizable form of plot and the themes are urgently contemporary. Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming conjures a world in a town, and its coda is nothing like I have ever read before or since. The Melancholy of Resistance offers some of both, with shorter sentences. For those resolved to start small, Spadework for a Palace can offer a taste of the archetypal style and madness. In any attempt, I might suggest new readers think of the experience like running: difficult at the beginning, euphoric at stages, biologically limited, and good for your health.

Seiobo There Below was an unorthodox place for me to start, but a revelatory one. It asked things of me that a book had not asked before: to simultaneously hang on tight and relinquish all control. It showed me a writer whose work is often perceived as chaos but in whom a reader can find meditation; escape from the rest of our frenzied world. I have since sought this feeling across his work. Revisiting that first sentence I’d read—the one people might actually want to try after this week’s prize—I see that it doesn’t just induce that feeling, it describes it. Krasznahorkai writes of a bird, that it

may bring its snow-white body to a dead halt in the exact center of this furious movement, so that it may impress its own motionlessness against the dreadful forces breaking over it from all directions, because what comes only much later is that once again it will take part in this furious motion, in the total frenzy of everything, and it too will move, in a lightning-quick strike, together with everything else; for now, however, it remains within this enclosing moment, at the beginning of the hunt.