Muriel Spark was a superstitious writer. In a 1971 BBC documentary, she explains her relationship with her pens. “If by accident someone picks up one of these pens … I throw that pen out the window. I don’t want to touch it for my book anymore.” In the footage, she’s not sure where to rest her gaze, but she’s delighted by her own eccentricity—by being a puzzle even to herself.

Exorcising the possessed pen suits a writer who heard voices and was “drawn to the magic universe of Catholic thought,” as her lover, collaborator, and eventual nemesis Derek Stanford described her. But the defenestration speaks to other aspects of her life and art: her fear of plagiarism, of being copied and accused of copying; her acquired loathing for collaboration even though (and probably because) co-authorship defined her early life as a writer; and lastly, the pen’s punishment for betrayal, which over time Spark came to expect as the consequence of success. Perhaps, in a bush somewhere, there lies a pen that let her down.

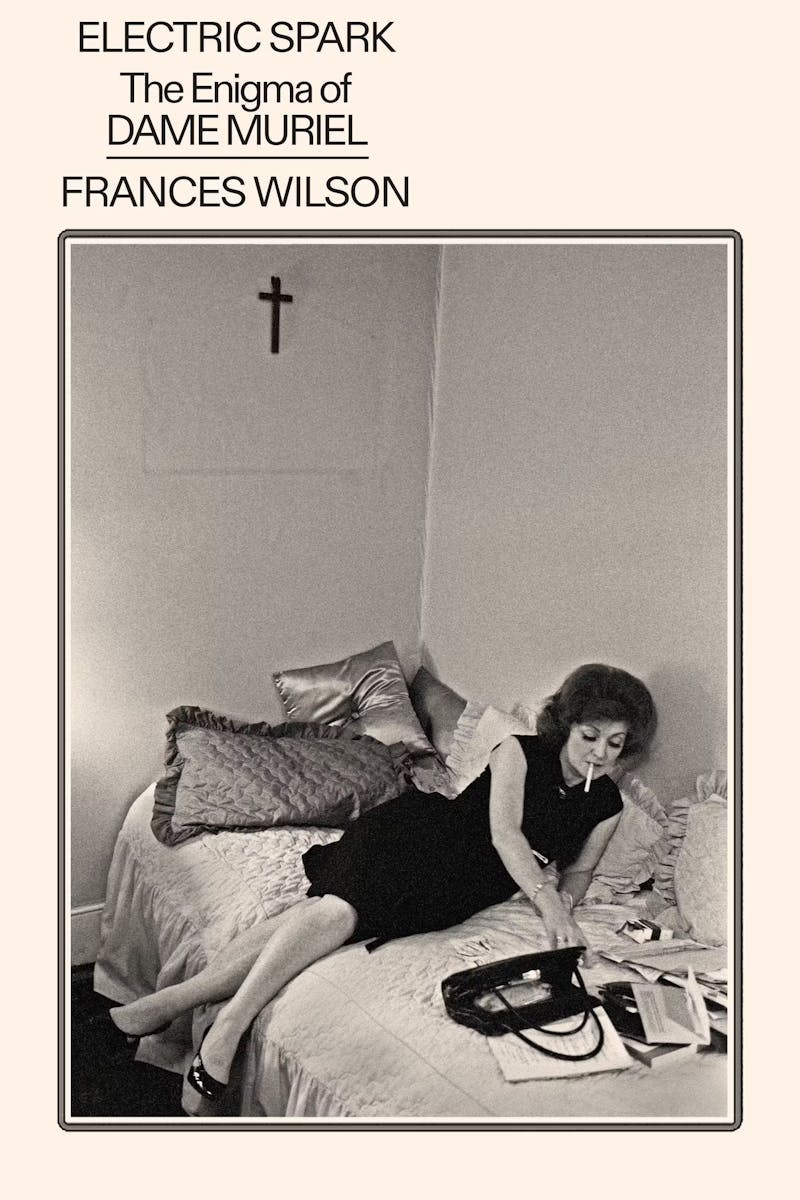

Frances Wilson tries to pick it up. In Electric Spark: The Enigma of Dame Muriel, Wilson places Spark’s superstitions center stage and guides us through a web of fate and coincidence. Wilson wishes to be possessed by her subject and says she feels, “on every page of this book, her control of my hand.” Earlier biographies have tried to cement or wreck Spark’s reputation. Martin Stannard’s Muriel Spark: The Biography is the authorized, exhaustive life—but Stannard, Spark’s handpicked biographer, is a cautionary tale: He was granted access until he delved too deep and lost his subject’s blessing. As a result, his book was delayed for years. Derek Stanford’s 1963 Muriel Spark: A Biographical and Critical Study is a half-assed hatchet job by a score-settling ex who envied her talent. And Curriculum Vitae, Spark’s attempt at doing the job herself, is an autobiography with what Wilson calls a “forced and unnatural” feel.

Finding imperfections in these projects, Wilson aims for something else. Her book “is not a revision of Martin Stannard’s biography,” she writes, and nor is it “the biography Spark wanted all along or even, strictly, a biography.” Spark came to view biography as a perverse art form—though she was once its capable practitioner, having written lives of Mary Shelley and Emily Brontë. She didn’t believe she experienced time as others did, and Wilson does her best to honor her by avoiding the march of chronological order—mostly by embroidering biographical events with the fiction that drew from them later on. “Causality is not chronology,” as Spark wrote and Wilson quotes twice.

Spark’s work does seem to reject the normal flow of time, especially when she forecasts the fate of a character at the beginning of a book. Taken together, the novels themselves defy sequence; her early work is as accomplished as her late. “It is striking how certain Muriel was in her footing,” Wilson writes. “There is as little self or sentiment in her juvenilia as in her adult writing.” Start anywhere, and move in any direction, and the author one finds is mature, assured, and herself. “The books rehearse, repeat, and anticipate one another,” Wilson writes, “eventually coming full circle.” She conveys a strong sense of Spark’s completeness at a young age, as if there were no time before the Spark we know. Electric Spark has to grapple with a contradiction at the heart of its project: It aims to trace how Spark became Spark but enumerates the ways she seemed to arrive fully formed.

“The Muriel Spark who interests me,” writes Wilson, “is not the grande dame of her last forty years but the young divorcee whose arrival in post-war London sent feathers flying and started all the hares.” Spark was born Muriel Camberg in Edinburgh in 1918 to a Jewish father and a Gentile mother. She excelled at school and won prizes for her writing from a young age. At 19 she married Sidney Oswald Spark (Ossie) and followed him to Southern Rhodesia, at the time a British territory and colonial apartheid state. They had a son, Samuel (Sonny), who changed his name to Robin and later became a painter and Orthodox Jew. As Ossie’s mental health deteriorated, Spark realized she had to escape. She began divorce proceedings and deposited her son at a convent school, then traveled to Cape Town to wait her turn to leave. In 1944, she secured a dangerous passage through U-boat-infested waters to return to Edinburgh and then to London.

Robin joined her a few years later, though he was mostly raised by Spark’s parents. On Spark as a mother, Wilson writes:

The only story we are told about her experience of motherhood is that the father had wanted to kill the unborn son whose birth then nearly killed the mother. Ossie’s own mother had died in childbirth leaving him to raise the baby, and Muriel later became fascinated by Mary Shelley, whose mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, died eleven days after she was born and whose novel, Frankenstein, also about a traumatic birth, asks whether it is more monstrous to be a rejecting parent or a demanding child.

In England, Spark found a job working for the Political Warfare Executive, an Allied propaganda outfit in Milton Bryan—a sleepy village in the Bedfordshire countryside—that created and broadcast misinformation to wound German morale. After the war she was appointed the general secretary of the Poetry Society, then became its editor in chief, an unhappy 18-month tenure during which she was harassed by backbiting mediocrities and members of a literary old guard still writing pastoral poems (“The trees and glades their vestal raiment wear”) and blanching at modernism.

Through her work at the Poetry Society, Spark met the two most important men of her romantic life, Howard Sergeant and Derek Stanford. Sergeant was tall, dashing, and married, and their labored affair involved exchanging many long and needy letters—the only record, according to Wilson, that Spark had any sense of “romantic love.” Stanford was much his opposite, “short, bald and mustachioed,” and, for many years, Spark’s intellectual co-conspirator. Both affairs ended in acrimony. Like Evelyn Waugh, one of her literary idols (Wilson reports that The Loved One is “the only novel Muriel wished she had written herself”), Spark had a mental breakdown and converted to Catholicism. Her first novel, The Comforters, was published in 1957 when she was 39 years old.

Wilson gives some of the novels more weight than others. The Comforters gets its own chapter, and A Far Cry From Kensington, Spark’s most autobiographical novel and one of her best, deserves the attention Wilson gives it. Spark liked having a character latch onto a phrase and repeat it, like Margaret in Symposium who sincerely and performatively expresses concern for “les autres” (“one has to think of les autres”), or Jane in The Girls of Slender Means referring to publishing as “the world of books,” or even Jean Brodie stressing to her pupils that she has entered her “prime.” (Spark’s narrators share this trait: In The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, the narrator relentlessly notes that Rose, one of the pupils, is “famous for sex.”) Spark took the device to its terminal point in Kensington, in which the protagonist Mrs. Hawkins (a Spark avatar) can’t stop calling the villainous hack writer (the Stanford stand-in) a “pisseur de copie.” The phrase is repeated 37 times, Wilson notes, a joke worn so well it becomes something else entirely—an incantation to ward off a demon of mediocrity.

Spark’s best novels have more of her in them, and in her very best books—The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, The Girls of Slender Means, and A Far Cry From Kensington—she casts the shards of herself into multiple characters, various and opposed. In Jean Brodie, Spark is Sandy, the teacher’s acolyte and betrayer, and later, a writer and nun; but Spark is also Mary, the “silent lump” who takes all the blame and later dies in a fire; and Spark is of course Jean Brodie herself, an iconoclast of customized Christian faith, a single woman who pursues love affairs but isn’t wife material. In The Girls of Slender Means, Spark is Jane, the chubby publishing assistant who eats chocolate to power her “brain work,” and Nicholas, a poet who converts to Catholicism and is killed on a mission in Haiti. In Kensington, Spark is Mrs. Hawkins, a young, overweight widow who lives in a rooming house and works as an editor; and Emma Loy, a brilliant author with a mysterious attachment to Hector Bartlett, the talent vampire. Their falling out prompts Hector to smear Emma in his memoir—much as Stanford did to Spark.

Spark’s fiction reveals the ways she perceived herself as multiple: beautiful and ugly, smart and stupid, cultured and naïve, crazy and sane, alive and dead. Wilson elegantly documents where Spark drew on her own life to write her fiction. Spark herself was the cherished pupil of an eccentric teacher, Miss Kay—the model for the ridiculous and enticing Jean Brodie—who called her students the “crème de la crème” and spouted delightful non sequiturs. Spark’s years of living in rooming houses, and her jobs in publishing, provided rich material for Slender Means and Kensington.

Her novels also show how she didn’t see herself: Mothers are mostly sidelined in her fiction, and though there are wives, the closest Spark analogs are rarely married. Spark never married after Ossie, though she wanted to. She was forever the other woman: Sergeant’s lover when he was married (he left his wife for another other woman), and Stanford’s lover when he wanted a wife—just not Spark, doubly tarnished by divorce and single motherhood. Spark can sympathize with the wives in her fiction (Teddy Lloyd’s wife in Jean Brodie or the ever suspicious Mabel in Kensington), but she didn’t see herself in them. Wilson notes that Spark was “undomesticated”—in the boys’ club of letters, it was one of her most endearing qualities.

There are moments in Electric Spark when the writing rises to a plausible imitation of Spark’s comic bleakness, her elegant deadpan. Wilson writes of Ossie, losing his mind in Southern Rhodesia, “He now had a pistol which he fired both inside and outside, and in the direction of his wife.” Describing Derek Stanford: “He could neither dance nor hold a tennis racket … and once left his typewriter on the district line.” But Wilson often repeats herself (faithful autobiography requires a “straight ghost,” we’re told, and, “Causality is not chronology”) and aims for clever turns of phrase that end up saying too little. “Once she had the security of God, Muriel stopped caring about style, and once she stopped caring about style she found her style in a stylized carelessness.” Or: “But she did not marry Ossie because he had the good fortune to be called Spark; it was because he was called Spark that Muriel was destined to marry him.”

From childhood Spark had a doppelgänger named Nita McEwen, a girl from the same Edinburgh neighborhood who, by coincidence, happened to be in colonial Africa at the same time—and who later, by another strange coincidence, happened to be staying with her husband at the same Victoria Falls boardinghouse as Spark and her husband. Like Ossie, Nita’s husband was mentally unwell, and in Victoria Falls he murdered her and killed himself—a traumatic event Spark wrote about in Curriculum Vitae.

The bombshell of Wilson’s research is that Spark seems to have invented her. There is no record of the crime or of a Scottish woman named Nita McEwen. Wilson notes that the name is an anagram of Twin Menace, suggesting something Spark both feared and coveted. Wilson writes, “Doppelgangers are dangerous, she knew from the Border ballads, because one of them has to die,” and Wilson argues that the invention and destruction of Spark’s dark double was an important step in her own artistic self-actualization. Perhaps Spark quietly wanted Stannard to discover the secret at the heart of her origin story. Wilson’s discovery is worth the price of admission.

“Sandy was fascinated by this method of making patterns with facts,” Spark writes in Jean Brodie. Perhaps the invention of Nita McEwen was Spark’s method of fabricating fact from pattern: the fact of violence by husbands against their wives. Wilson writes that Spark provided a cause for an effect—to make more explicit her fear of Ossie and to overcome the guilt of leaving husband and son behind.

It’s tempting to read the fiction of Nita for more impish reasons too, as if the puzzle-loving Spark wished to encrypt her own biography. The demise of Spark’s double also reflects the author’s broader draw toward violence. She most explicitly articulated her morbid curiosities in The Driver’s Seat, her nouveau roman about a woman who, determined to be murdered, goes about appointing her killer. The spectacular deaths in her fiction can read as dark fantasies. Spark hangs brutal fates upon her characters like jewels, and it’s never clear if their burning, drowning, or stabbing leads to damnation or salvation. Nita, a fiction, died violently, faultlessly; Spark, the flawed survivor, earned the privilege to toil on but was denied the neatly dramatic end. She suffered for it: “Cursed” is the word Wilson uses to describe the storm of afflictions—a gruesomely botched hip replacement, kidney and eye operations, a near-fatal case of shingles—Spark endured in the final 14 years of her life. She died of cancer at age 88.

Like Sandy in Jean Brodie, Spark contemplated “a dark and terrible salvation which made the fires of the damned seem very merry to the imagination by contrast, and much preferable.” In the story of Nita and Spark, it’s unclear which woman was saved, who was damned. The invention of Nita McEwen reveals how deeply Spark came to think of that moment in her life as its deciding event, the fork in the road. “She thinks she is Providence,” Sandy says of Jean Brodie. “She sees the beginning and the end.” By avoiding becoming the murdered wife, she chose—and made—her own life. She was, as ever, the other woman.