It’s the hubris that really galls.

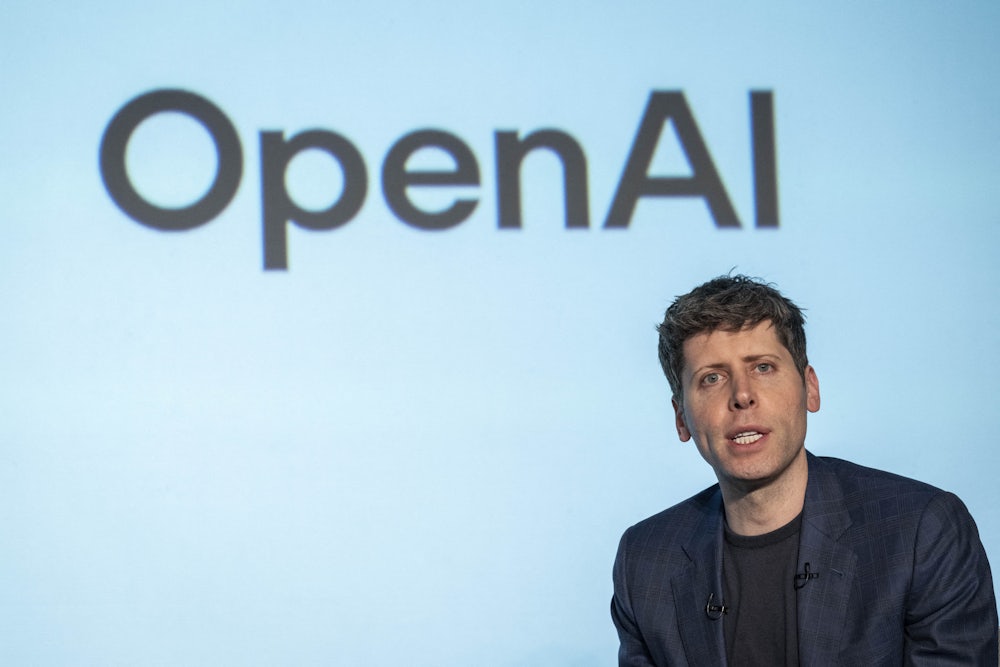

Last week, while recording a podcast at the abundance-themed “Progress Conference,” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said, “When something gets sufficiently huge, whether or not they are on paper, the federal government is kind of the insurer of last resort, as we’ve seen in various financial crises.… Given the magnitude of what I expect AI’s economic impact to look like, I do think the government ends up as the insurer of last resort.”

It would be ill advised, amid the populist surge in American politics, for even a well-liked leader of a well-liked industry to come out and say they’re expecting American taxpayers to bail them out if and when the need arises. Altman is not well liked, and neither is his industry. In fact, AI billionaires may soon become among the top villains in American society. It’s a dynamic that could provide Democrats with the perfect wedge issue to ride back to power—if they can muster the political courage to take the people’s side over that of some of the country’s wealthiest corporations.

Last week’s election results demonstrated the first concrete proof of the potency of an anti-AI message, as the effects of AI data centers on utility bills played a significant role in several major Democratic victories. In New Jersey, Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill’s closing argument was a pledge to freeze electricity rates, which have soared because of data-center demand. In Virginia, Governor-elect Abigail Spanberger won after pledging to make data centers “pay their own way,” and many Democrats went even further. At least one candidate, John McAuliff, flipped a seat in the House of Delegates by focusing almost entirely on tying his Republican opponent to the “unchecked growth” of data centers, with an ad that asked, “Do you want more of these in your backyard?” And in Georgia, Democrats won their first nonfederal statewide races in decades, earning 60 percent of the vote against two Republican members of the Public Service Commission by criticizing Big Tech “sweetheart deals” and campaigning for policies “to ensure that the communities that they’re extracting from” don’t end up with their “water supplies … tapped out or their energy … maxed out.”

As these election results suggest, data center opposition is remarkably bipartisan. A large proportion of Big Tech’s AI infrastructure buildout is occurring in red states, like Indiana, Texas, Ohio, and West Virginia, where data centers have added billions of dollars to household energy bills and inspired serious hostility from Democrats and Republicans alike. As one conservative anti–data center activist in Oklahoma said, “We’d probably see our elections flip, too, if people started running on it.” Or as Virginia state Senator Danica Roem put it, “There are a lot of people willing to be single-issue, split-ticket voters based on this.”

You would think that such an intensely cross-cutting issue would be at the center of Democrats’ monthslong debate over their party’s future. But many of the voices that have been most vocal on the need for the Democratic Party to begin competing in Republican-leaning areas have been entirely silent on this topic. None of the recent reports from centrist and abundance advocacy groups like WelcomePAC or Searchlight even mention AI or data centers—which makes more sense when you learn that these organizations are themselves funded by Big Tech billionaires, who have also begun outfitting massive super PACs with hundreds of millions of dollars to influence pro-AI policies in Washington.

Here is a clear and simple way for Democrats to transform their party’s brand to appeal to working Americans who are being crushed by high costs and angry at a system that feels rigged against them. Because, as electorally compelling as an anti-AI position is today, it will become politically essential in the years ahead—for three important reasons.

First, there is the likelihood that the AI industry is building up a bubble that, when it bursts, will take down the global economy. OpenAI is currently valued at $500 billion, and is laying the groundwork for a $1 trillion initial public offering. This valuation is speculative, rather than based on the company’s earnings, which are abysmal. In the first half of 2025, OpenAI made $4.3 billion in revenue and posted a net loss of $13.5 billion, a ratio that is only getting worse as its capital expenditures continue skyrocketing. Even more infuriating, AI billionaires seem to be purposefully inflating this bubble with sketchy circular financing strategies, in which companies like OpenAI receive billions of dollars in investments from chipmakers, cloud computing companies, and other Big Tech corporations, which they then send back to those same companies to pay for chips, computing power, and other services.

When this thing pops, it won’t be the filthy rich scammers behind the bubble who will lose out. It will be regular people: One former International Monetary Fund chief economist estimates that a crash could wipe out $20 trillion in wealth held by American households. Meanwhile, as Altman’s quote at the top of this essay foreshadowed, AI billionaires are already maneuvering for taxpayers to bail them out of the crisis they are willfully creating, with OpenAI’s chief financial officer recently suggesting that a government loan guarantee might be necessary to fund the investments needed to keep the company afloat. It’s pretty easy to predict how all of this will go over with the voting public.

Beyond the profoundly compelling politics of a market crash and bailout, there’s the equally potent issue of AI-driven job losses. These hits have already begun. Last summer, IBM replaced hundreds of employees with AI chatbots, and UPS, JPMorgan Chase, and Wendy’s have all begun following suit. The CEO of Anthropic has warned that AI could lead to the loss of half of all entry-level white-collar jobs; McKinsey estimated that AI could automate 60 to 70 percent of employees’ work activities; and a recent report from Senator Bernie Sanders and the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee found that AI could replace 89 percent of fast-food and counter workers, 64 percent of accountants, and 47 percent of truck drivers. The anger that such dislocations will generate against “clankers”—yes, anti-AI frustration has already inspired the explosion of a Gen Z meme-slur—is hard to overstate, potentially exceeding the resentment against the North America Free Trade Agreement that Trump rode to the White House in 2016. Democrats should be doing everything in their power to get on the right side of that voter fury.

Finally, there’s the more immediate, enshittifying reality of AI’s actual effects on our daily lives, which bear so little resemblance to the tech-utopian tall tales that Big Tech has been spinning. We were promised cures for cancer. What we got instead was a technology that’s impoverishing millions of artists; undermining the economic foundations of journalism; filling the internet with unbearable slop; forcing itself into every nook and cranny of our digital landscape; damaging public trust in our elections; exacerbating the epidemic of loneliness and alienation among adolescents; inspiring genuine psychosis in users; undermining our critical thinking skills; exposing children to sexual content; and even, in far too many instances, egging on young people to kill themselves.

Americans understand they’re getting a raw deal on this. A Pew Research Center poll in the spring found that only 17 percent of Americans believe AI will have a positive impact on the United States over the next 20 years, while only 11 percent say they are more excited than concerned about the increased use of AI in daily life, compared to 51 percent who say the opposite. And a January Axios poll found that 72 percent of Americans have a negative opinion about how AI will impact the spread of false information, with 64 percent saying the same about its impacts on social connections.

Of course, not everyone feels this way. But it’s worth noting that concerns about AI are particularly prevalent among the working-class voters that Democrats have felt the greatest urgency to win back. According to an April Quinnipiac poll, while the majority of wealthy Americans thought AI would do more good than harm in their day-to-day lives, Americans earning below $50,000 thought it would do more harm than good, by a 2-to-1 margin, with only slightly better numbers for Americans in the $50,000–$100,000 income range.

All of these interconnected dynamics are coming together to create a massive opening for Democrats to eviscerate the Trump administration, which has gone all in on fast-tracking permitting for AI infrastructure, rolling out the red carpet for AI billionaires, and even threatening to cut federal funding for states that try to regulate AI. But to fully exploit that opening, Democrats must be able to point to an authentic and believable—in short, a real—record of standing up to the industry. That may require a fight with members of the party’s corporatist wing, who remain ever ready to sacrifice Democrats’ electoral odds at the altar of their big-business backers.

Confronting AI’s modern-day robber barons could be rocket fuel for the Democrats in 2026 and 2028. The party is increasingly focused on oligarchic power and affordability concerns, and here’s a winning issue that unites those messages. It’s such an obvious opportunity that it should not require much persuasion. But can the Democrats see that—or can they be made to?