The internet is going gaga for gay sheep of late. Or, more precisely, the wool from gay sheep. On November 13, the LGBTQ dating and sex app Grindr put on “I Wool Survive,” a runway fashion show in New York City that leaned all the way in. There was a swimmer wearing stars-and-stripes Speedos, a mechanic in black overalls unzipped south of his bellybutton, a football player in only a jockstrap and a crop-top jersey (number 69, of course), and an afterparty at The Eagle. All the pieces in this celebration of camp were hand-knitted by designer-to-the-stars Michael Schmidt out of wool sourced from Rainbow Wool, a German nonprofit that rescues from slaughter male rams who prefer the company of other male rams.

The message was simple: Homosexuality exists throughout the animal kingdom and should be protected and celebrated there too. “It’s an animal rights story. And it’s a human rights story,” Schmidt told The New York Times. This feel-good narrative has gone viral, garnering glowing coverage from mainstream publications like the Times, The Washington Post, and Esquire; fashion and art outlets like Hyperallergic and Paper; and gay mainstays Out and Pink News, and blowing up across social media.

But the tale of the rescued gay rams is not actually a feel-good story. It only looks that way because the public is largely unaware of how the sheep industry operates. Gay rams, who refuse to breed with ewes, aren’t the only animals the industry deems unprofitable to keep alive. It passes that same judgment on breeding ewes worn out from too many pregnancies and older sheep who don’t produce enough high-quality wool. Eventually, they all get sent for slaughter, just like most male sheep, the overwhelming majority of whom are castrated as lambs and slaughtered before their first birthday. If anything, the gay wool fashion show should make us think not about the good fortune of the few rescued rams but about how animal farming systematically, routinely, and often violently exploits the reproduction of all the animals it encounters.

Sheep farming is among the smallest and least industrialized of major livestock industries, in part due to comparatively low demand for wool and mutton. Sheep, which need to graze for their entire lives, are also a bad fit for the factory farm and industrial feedlot system that dominates modern animal agriculture. There are about five million sheep in the United States and just over a million and half in Germany, where Rainbow Wool is based. Compare that to, respectively, 1.5 billion and 160 million chickens in the two countries at any given time. But this doesn’t make the basic logic of commercial sheep farming all that different from other forms of animal agriculture.

In the U.S. and Europe, sheep are raised primarily for their meat, called “lamb” when it comes from animals slaughtered under 12 months. Farmers usually shear meat lambs prior to slaughter, while sheep from wool breeds are culled for “mutton” when their hair begins to turn brittle at around the age of 6.

But animal agriculture doesn’t just require animal bodies and substances to be turned into consumer products, such as meat, wool, leather, and milk. Farmers must also exploit the animals’ reproductive processes to maintain and grow their flocks. Every ewe is a living factory for future generations of sheep, while ram sex work is more selective: Farmers only need one ram per flock, and can reliably mate a single ram with as many as four or five ewes every day.

The other rams become what are called wethers. They are typically castrated a few weeks after birth to prevent unlicensed pregnancies, because they tend to be more docile than intact rams, and because of the alleged superiority of their meat. Regardless, castration, not breeding, is the typical ram destiny.

This is what one of us—Gabriel, a professor of gender, sexuality, and feminist studies—has previously dubbed the “brutal, violent heteronormativity” of animal farming: It’s not that farmers are intentionally hostile to gay animals, but rather that all breeding livestock are ruled by the imperative to breed or die, reducing them to their reproductive potential. This is even more the case in the factory farming that dominates meat production and makes meat cheap. This model depends upon minutely controlling animal sex. Or, as the feminist philosopher Carol Adams argues more forcefully, meat and other animal products require sexual exploitation.

Public discussions of agriculture mostly ignore the details of breeding. Most people, and certainly those who traffic in nostalgic celebrations of old-time farming, tend to present farming as a business in which humans merely harvest what natural reproduction gives us. But in industrial production systems, mating has to match the market’s schedule and standards. Nearly all dairy cattle, swine, and turkeys are bred through artificial insemination.

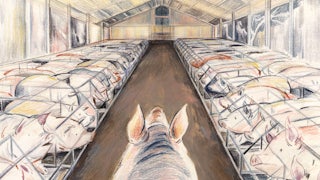

The details may ruin your next pork chop. In most factory pig farms—as anthropologist Alex Blanchette’s work shows in uncomfortable detail—mostly male human breeding technicians sit on the backs of sows, pound their flanks, stroke their teats, and otherwise simulate the activities of boars during mating to prepare them for artificial insemination with semen from boars housed tens, hundreds, or thousands of miles away. Boar semen, in turn, is harvested using mechanical vaginas, but human technicians typically must stroke the boar to induce an erection before inserting his penis into the contraption.

Such interventions in the sex lives of animals are so intrusive and ubiquitous that the laws criminalizing animal cruelty and human sexual abuse of animals—“bestiality” laws—had to be rewritten to include explicit exceptions for farmers.

But even outside the cruel industrial system, most agricultural animals find their sexuality almost completely subordinated to the dictates of the market. Rams that do breed with ewes do so under close observation. Farmers carefully apply distinctly colored paints to each ram’s undercarriage so that they can track which rams are breeding which ewes. Rams that don’t spread their paint have no future. It is inapt to apply human identity categories like “gay,” founded on ideals of sexual autonomy and desire, to this system.

One in 12 rams are gay, coverage of the Grindr and Rainbow Wool show has repeatedly asserted. But where does this estimate come from?

Scholarly literature, cited in the New York Times article, purports to reveal “sexual partner preference” among farmed rams. In those studies, tested rams were prevented from mating for around a week, and then they were given the choice of two ewes and two rams restrained in a stanchion. Scientists recorded the results.

It’s hard to know what, if anything, this experiment shows. Even for humans, the word gay is slippery. It is used interchangeably to describe three distinct things: behavior (sex acts), orientation (sexual desires), and identity (the “kind” of person one is, where sexuality is given special significance).

You can’t ask rams about their identities, and we have no evidence that sheep ascribe any special significance to sex in the way humans often do. Calling rams gay risks either imputing human thoughts and feelings to sheep—what scholars call anthropomorphism—or distorting what people mean by gay. Gay usually doesn’t just describe sex acts; it also encompasses how gay people relate to institutions like marriage and kinship, and linked resources and rights.

If we cannot sensibly talk about gay sheep identity, perhaps we can think about gay sheep behavior, which is what the cited studies examine. Same-sex sexual behavior is common among animals in the wild, including among wild sheep. It is also visible on farms, as observant farmers have been chronicling for ages.

In the most influential study of the subject, “stimulus animals” (what they call the bottoms and a phrase that admittedly would look great on a cropped tee) were either those previously observed to be engaged in receptive sex with other rams, and therefore deemed suitable mounts, or those “test rams” that had already exhibited a preference to top other rams. The study designers assumed that once a ram had topped another ram it was suitable as a “stimulus animal.”

But this is a big logical leap. Defining sexual preference exclusively in terms of “topping,” and not necessarily on willing partners, is taking phallocentrism to the extreme. That’s how farmers think about sheep sex, since they need to exploit it, but is that how researchers should think about it? What if no rams like being topped? Perhaps some rams who like to top ewes also like to be topped by other rams. Perhaps some rams would simply prefer not to top or be topped by anyone. We cannot know from the cited studies. If these rams are gay in the way most people mean it, we would need evidence of both topping and bottoming, and other things besides, options the studies fail to anticipate because they’re not actually designed to study sheep sexuality. They’re designed to exploit it. This is what the Rainbow Wool sweater hype ignores: Most of what we know about the sexual behavior and preferences of farmed animals comes from research distorted by questions about how to more efficiently extract profit from the loins and labors of livestock.

If the idea of “gay” rams is so confused, are people wrong to want to save them? No. But that doesn’t mean Schmidt or Rainbow Wool are a very good vehicle for this work, either.

Garnering support for farmed animals is difficult and expensive, particularly if one wants to do something more than just convince people to abstain from ordering lamb. As evidenced by the work of scholars like Elan Abrell, sanctuary farms—those that save animals from grim fates in farming and let them live out their lives as naturally as possible—take land, money, and hard work and have almost no conceivable way of turning a profit. In this sense, Rainbow Wool, in selling wool from the rescued animals so they pay their way—and, yes, helping support queer charities in Germany—is a way of commodifying animals as gently as possibly while saving them from the butcher’s blade. And selling products means advertising, like having high-visibility runway shows of gay fashions knitted from the wool of gay rams.

Anthropomorphizing animals as “gay” may be a worthwhile first step in getting people to recognize the sexual exploitation that nearly all farmed animals endure. And in its own limited way, Rainbow Wool does this. Buying some fancy wool is hardly enough to address the harms of animal farming, but that doesn’t mean it’s worthless. When it comes to the politics of meat, people often pit individual action against transformative “systemic” change. In our forthcoming book, we argue that it’s wrong to treat individual and collective actions as either/or; we need both. Sometimes small incremental changes by individuals can help create new norms that lead to policy changes and eventual structural transformation.

Schmidt may indeed be doing some good, but it’s not nearly good enough. In fact, the farm on which Rainbow Wool’s gay rams are housed is also a commercial sheep farm, where other sheep are sent to slaughter. “It is a great capitalist story framed about being about gayness,” Carol Adams explained to us over email, of the Grindr fashion show. But “it doesn’t challenge animal agriculture in terms of assumptions about the requirement that animals be productive; nor about making females pregnant, nor about wearing wool.” Neither Rainbow Wool nor Grindr responded by publication time to a request for comment for this piece.

Consumers moved by the Grindr show could buy some Rainbow Wool wares, but they would do even better to send their money to a sanctuary farm with a broader perspective on animals and the industry that exploits them. And they would do better to educate themselves about how and why animal farming operates as it does, and what actions we can take, alone and together, to make it less harmful to the billions of animals it propels into lives of suffering and exploitation.