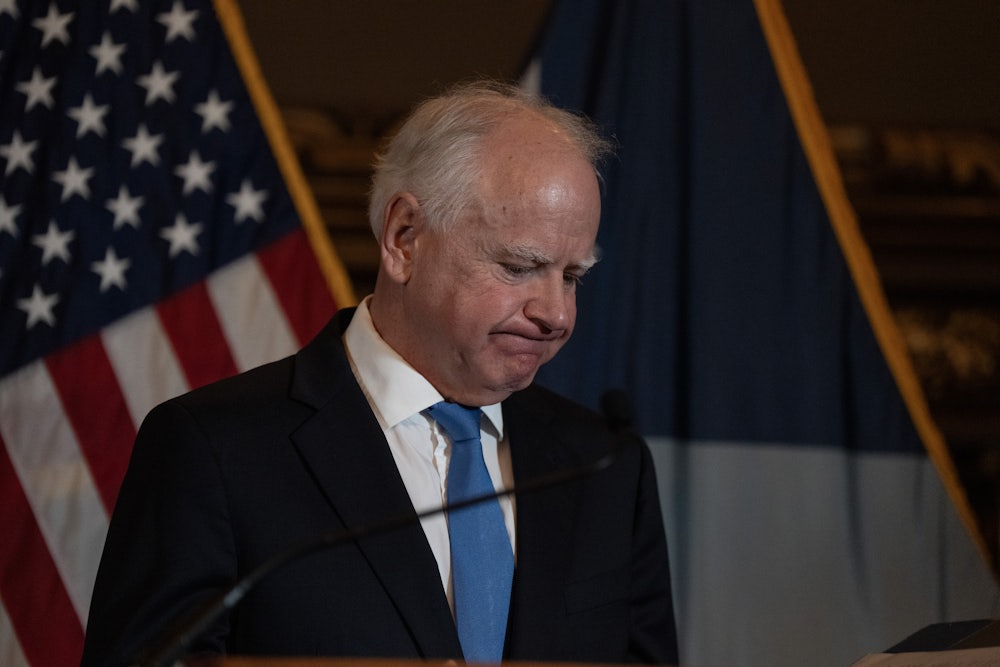

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz has abandoned his 2026 reelection campaign. In his announcement Monday, Walz pointed to right-wing conspiracy theories about the state’s Somali immigrant community as having played a part in his decision. It has been nine years since Pizzagate, and yet such conspiracy theories have gotten worse—and as they have further eroded many people’s sense of shared political reality, combating them has only become harder.

Late in December, YouTuber Nick Shirley recorded himself going to several childcare centers in Minnesota, an attempt to “prove” that Somali immigrants have been using the centers to steal public money. When Shirley showed up, at least one childcare center did not open its door, one owner said, “because we thought it was ICE.” The resulting video was quickly rebutted and fact-checked: The state’s Department of Children reported the childcare centers he descended upon were “operating as expected.” In fact, the state had investigated and prosecuted overbilling by some childcare services in Minnesota in the past; there have also been several unrelated, high-profile fraud prosecutions involving other Minnesota social services. Some of the ten childcare services Shirley targeted, The 19th reported, have had violations for issues such as cleanliness or maintaining allergy and immunization records, but none of those investigations found fraud. Shirley’s video, then, was purely propaganda.*

The debunking didn’t matter. By then, the video had millions of views, and the childcare center “fraud” narrative had become part of the right-wing cable news cycle of anti-immigrant grievance and cruelty. Workers at the childcare facilities Shirley targeted said they had received “hateful” and “threatening” messages. One day care center reported a break-in, and sensitive documents were found missing.

The conspiracy theory was always thin, and never actually implicated Walz. Nevertheless, Walz found himself defending his administration’s actions to stop fraud, and he cited the chaos caused by the video in his announcement abandoning his campaign on Monday. He called Shirley a “conspiracy theorist” and he accused Trump, accurately, of “demonizing our Somali neighbors.” But he was still leaving the race: “I can’t give a political campaign my all,” said Walz. “Every minute I spend defending my own political interests would be a minute I can’t spend defending the people of Minnesota against the criminals who prey on our generosity and the cynics who prey on our differences.”

It’s all too easy to see the parallels to real-world chaos caused by Pizzagate, and the incident nine years ago that signaled to the public how right-wing conspiracy theories had become more serious and dangerous. Then, in 2016, a gunman entered a Washington, D.C. restaurant, convinced by Twitter conspiracy theorists like Jack Posobiec that he could save children who were being trafficked for sex in its basement by a ring they claimed was organized by and for Democrats. The restaurant, Comet Ping Pong, did not have a basement. No one was physically harmed. For most people, news of the gunman’s arrest was their first exposure to such gruesome sex-trafficking conspiracy theories, which to that point were largely the province of marginal media figures feeding them to their growing online audiences.

It has often felt as if Pizzagate never ended. Long after it faded from public attention, Jack Posobiec now has the ear of the president—who, after the Shirley video, suspended childcare funding to the state of Minnesota. The conspiracy theories motivated Trump to take swift action. Trump himself, at the same time as the childcare center videos were circulating, was posting a video on his own social media about the Democratic lawmaker Melissa Hortman, promoting the conspiracy theory that Tim Walz had her assassinated. (The man indicted for Hortman’s murder and currently awaiting trial also targeted other Democrats and abortion providers, and is reportedly a Trump supporter who considered himself to be engaged in spiritual warfare.)

Politics now play out parallel to conspiracy theories, expressing them and promoting them. This has been building for nearly a decade, while attempts to counter them can barely keep up, and don’t seem to stop them. Fact-checking responds to conspiracy theories as if they are isolated incidents that can be corrected, and not common and regular expressions of the political and media ecosystem in which we live.

Over the last decade, each time such conspiracy theories take hold, break containment, and begin to widely circulate, a whole host of anti-misinformation experts, researchers documenting the far right, historians and journalists tracking the rise of Christian nationalism, fact-checkers and defenders of legacy media, and lobby groups for online and child safety attempt to respond. The idea that we can set the truth right is also appealing to those in the media, who, on our better days, believe facts are capable of making change in the world.

It is increasingly common, however, for those who benefit from the rise of conspiracy-theory politics (influencers, content creators, and even elected officials and the mainstream of the Republican Party), to then target those misinformation experts and fact-checkers. In the immediate aftermath of the January 6, 2021, attacks on the Capitol, it briefly looked like Republican members of Congress recognized the threats posed by conspiracy-theory politics: Their own lives were threatened by believers of election conspiracy theories promoted by the outgoing president. But since then, Republicans have mainstreamed the idea that they are under attack not from conspiracy theorists but from content moderators. They have made dismantling infrastructure for combating misinformation and disinformation a major part of their agenda. “Even before Donald Trump returned to the White House, the anti-anti-disinformation movement had chalked up a series of victories with a common set of tactics, combining independent media pressure, congressional scrutiny, and lawsuits that sometimes ran all the way up to the Supreme Court,” writes journalist James Ball in a recent story for The Verge, tracing the battle.

It should be a wake-up call: Misinformation and disinformation have potentially pushed a state governor out of seeking reelection, and appear to be on the cusp of taking away childcare from more than 20,000 children in Minnesota, thanks to the Trump administration halting federal funds over these fictions. Now the administration is reportedly planning to cancel funding for children and other social services to four additional Democrat-led states, premised on the same stories about immigrants stealing. These tales are perfectly suited to Trump’s politics of grievance, defining a set of enemies who are always stealing what’s rightfully the property and province of “real” Americans.

Misinformation and disinformation are how these people attain and build power. It’s why they fight to protect communication and political channels in which to push lies, scapegoating, and propaganda. It’s why you can’t fact-check your way out of a conspiracy theory or disinformation. This was true in 2016, when Trump was a joke. It was true in 2020, when Trump was a loser. It’s true now, with Trump in power again. There is still no coordinated response to misinformation that appears capable of confronting that truth: Lies are powerful. So long as there are people who can benefit from conspiracy theories, there will be people pushing them.

* This piece has been updated with further reporting about the fraud allegations.