In a viral video captured during the ICE surge in Portland, Maine, an agent pointed his phone at a constitutional observer, snapped a photo, and offered a chilling, off-the-cuff warning: She was being added to a “database” of “domestic terrorists.” The brief exchange offered a glimpse into the petty and vindictive mindset of ICE agents. It also offered us a window into the mechanics of a hyperefficient, privatized surveillance state, one that bypasses the pesky barriers of the Fourth Amendment by putting our user data on the government’s credit card.

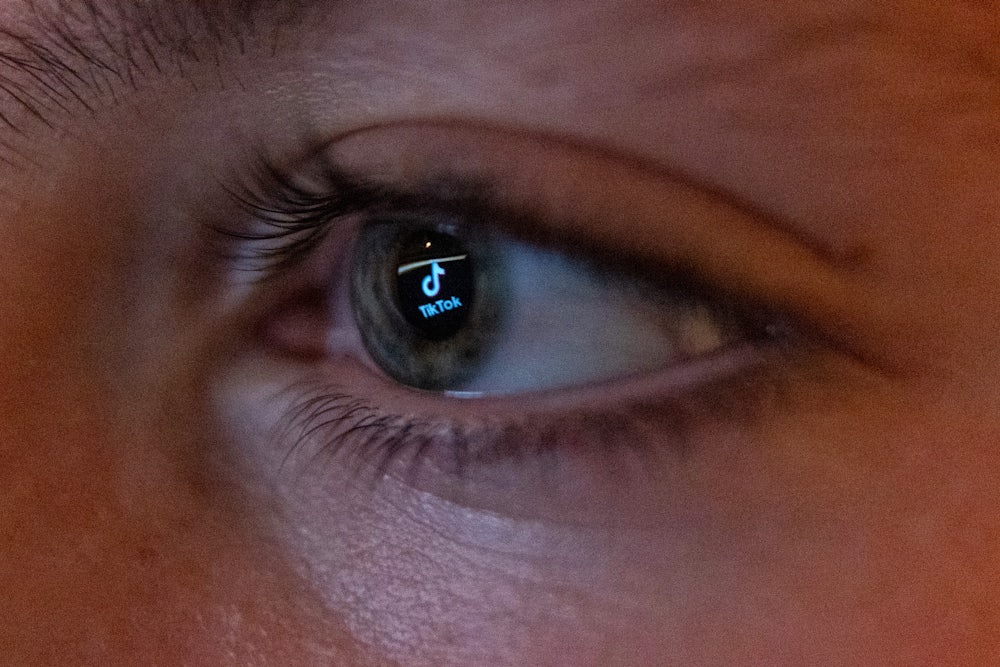

Last month’s Americanization of TikTok is perhaps the zenith of this strategy. While liberal hawks cheered the platform’s transition to the jumble of jargon now known officially as TikTok USDS Joint Venture LLC as a win for national security, they ignored the details written in the fine print. TikTok’s Privacy Policy has for some time included tracking of location and citizenship status (among other identity markers, such as sex). They’ve recently updated their language to add more specificity about the personal data they track so as to be in compliance with state laws.*

By housing TikTok’s data on Oracle’s cloud infrastructure—a firm whose multibillion-dollar existence is owed in part to U.S. intelligence and law enforcement contracts, and whose co-founder Larry Ellison recently bragged about AI ushering in an era where “citizens are on their best behavior”—the government has finally achieved its aim of securing the app by integrating it into its domestic surveillance dragnet. Considering the drive to secure TikTok was driven by fears of what the notoriously repressive nation of China might do with our private data, this outcome is, at the very least, highly ironic.

The technical wizardry of this surveillance relies on your Mobile Advertising ID, or MAID, a unique string of alphanumeric characters assigned to every smartphone. Every time an app, be it TikTok or a simple weather tracker, makes a bid to show you an advertisement, if your location services are enabled, it shares both your MAID and your precise GPS coordinates to thousands of private bidders. In the past, this metadata has been used by the Pentagon to identify targets.

Data brokers like Venntel and Babel Street harvest these “bid-stream” crumbs into massive, searchable oceans of movement. For ICE, this means they no longer need a wiretap; they can access a digital twin of your life, where your TikTok scrolling habits are pinned to a physical map of your home, workplace, and your child’s school or day care.

The Fourth Amendment nominally requires a warrant and probable cause to search your person or effects. But in the age of surveillance capitalism, the Department of Homeland Security has discovered a loophole: Why bother with a judge when you can just buy the data from a private broker? This is the spending-around strategy. By leveraging data originating from TikTok and similar platforms, ICE no longer needs to infiltrate communities. They simply tap into the flow of data already being harvested by private entities, allowing them to target both the undocumented and the political opposition.

Once this data enters the DHS ecosystem, it doesn’t sit in a silo. It’s fed into a high-tech meat grinder of enforcement tools designed to identify and disappear people with industrial efficiency. These include ICE’s ELITE app (developed by Palantir), which fuses government and private data to generate neighborhood maps and individual dossiers of targets, each with an individualized “confidence score.”

This app can tap into everything from Flock license plate readers to Ring cameras, allowing ICE to follow targets without being physically present. One can easily imagine a scenario where data originating from TikTok provides the last missing piece—user location and citizenship status—that ICE needs to green-light one of its raids.

Perhaps most dangerously, ICE is now utilizing advanced social media monitoring to perform “sentiment analysis.” By scraping TikTok and other platforms, they can monitor the emotional and political temperature of entire geographic areas, identifying resistance hot spots. This completely undermines the particularity requirement of the Fourth Amendment.

Legally, this system is built on the crumbling foundation of the third-party doctrine, a legal relic from the 1970s. This doctrine posits that individuals forfeit their “reasonable expectation of privacy” the moment they “voluntarily” share information with a third party, like a bank, a phone company, or a social media app.

While the Supreme Court’s 2018 Carpenter v. United States ruling suggested that tracking a person’s location via cell towers requires a warrant, DHS has sidestepped this by arguing that purchased data is fundamentally different from subpoenaed data. In the eyes of DHS, when ICE buys a location profile from a broker, it isn’t conducting a search of a person, it’s completing a commercial transaction with a business.

It increasingly seems that the Americanization of TikTok was never about protecting us from a foreign adversary. It was a tactical acquisition of digital infrastructure. Trump’s DHS is treating the Bill of Rights like a market inefficiency—a cost of doing business that can be mitigated through the right corporate partnership. In this case, it’s working hand in glove with the social media platform favored by America’s most politically active demographic cohort.

Fortunately, there is a legislative solution. Congress should move immediately to pass the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, or FANFSA. This law would prohibit law enforcement and intelligence agencies from purchasing data, such as a user’s location or viewing history, that would otherwise require a warrant, court order, or subpoena. The House passed the bill with bipartisan support in 2024 before it stalled in the Senate.

The legal architecture of FANFSA is designed to codify and expand upon the Supreme Court’s Carpenter ruling. In that case, the court recognized that the “near perfect surveillance” enabled by digital location data requires a warrant, even if that data is held by a third party. However, Carpenter left a gaping hole: While it restricted the government from compelling companies to hand over data without a warrant, it remained silent on the government simply purchasing that same data on the open market.

FANFSA seeks to bridge this gap by amending the Stored Communications Act to prohibit law enforcement and intelligence agencies from using “anything of value” (in this case, taxpayer dollars) to bypass judicial oversight. By doing so, the Act effectively asserts that the third-party doctrine cannot be used as a commercial loophole to circumvent the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement.

The Americanization of TikTok has also introduced a more visible form of suppression through the algorithmic throttling of dissent. In the wake of recent ICE shootings in Minneapolis, users and high-profile creators alike reported that anti-ICE videos were instantly met with “zero views” or flagged as “ineligible for recommendation,” effectively purging them from the platform’s influential “For You” feed.

The new TikTok USDS Joint Venture LLC attributed these irregularities to a convenient data center power outage at its Oracle-hosted facilities. While the public attention this episode garnered will make it more conspicuous if user content gets throttled on TikTok again, the tools are there: By leveraging shadow bans and aggressive content moderation, TikTok can, if it wanted to, ensure that any visual evidence of ICE’s overreach is silenced before it reaches the masses.

When the government can buy its way around the Constitution, the result is what we saw in Portland: an ICE agent labeling a citizen a “terrorist” for exercising her First Amendment rights. If Congress allows these private data loopholes to stand, ICE’s database will soon include anyone who dares to criticize the administration. And content filtering will ensure that any video record of ICE violating our civil liberties will remain unseen.

When that happens, the Roberts court won’t need to gut the First and Fourth Amendments. It can just wait until everyone agrees to the privacy policy.

*This article originally misidentified TikTok’s privacy policy. It also misidentified the extant privacy policy as an updated one.

This article has been updated throughout for clarity.