Presidential debates are not held for the purpose of informing the public about the candidates running for president and their views. They are television shows, designed to do what other television shows do: get ratings, sell perfume and laptops, drill the significance of the wretched Geico lizard into our skulls. Political substance as a by-product of the profit motive: This is what passes for democracy in America. But let’s imagine a better world, one in which we could expect the moderators to ask questions that actually enhance our understanding of the candidates’ policies and not just spark the best spats and yield the cleverest zingers. With a field that’s likely to be blissfully smaller than ever, next week’s debate in Iowa, to be moderated by CNN and the Des Moines Register, is fertile ground for this sort of fantasy.

In the first few debates, the moderators approached the task of differentiating the candidates’ health care platforms with narrow goals in mind: challenge the Medicare for All proponents on the prospect of private insurance being eliminated or on whether middle-class taxes would go up. These inquiries did not actually seek to get more detail from candidates on how their policies would achieve these ends, but rather to force them to admit that their proposals were politically dangerous. Thankfully, the moderators of the more recent debates have gotten bored of these questions. So let’s imagine that next week’s interlocutors could ask some specific and useful questions about health care—what would those be?

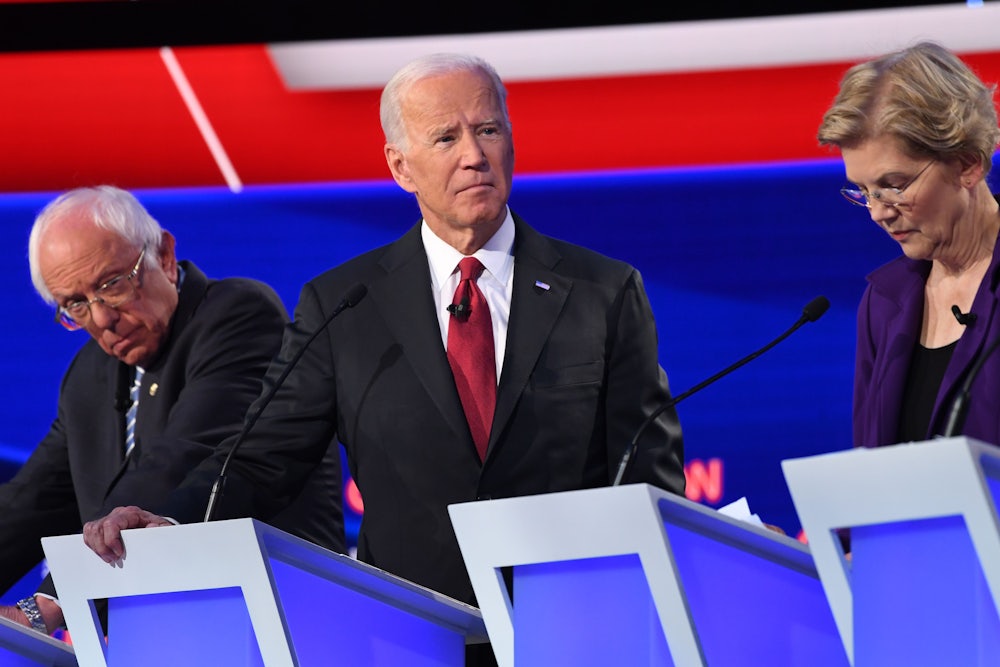

To start with the biggest ask possible: Could a debate moderator please ask Joe Biden to explain, clearly and in his own words, what the following terms mean: Deductible, co-pay, co-insurance, and premium? In previous debates, Biden has demonstrated that he does not have any kind of grasp on the particulars of health care policy. This is fine in most walks of life but is not actually acceptable if you want to be president. He routinely confuses key terms, such as one bizarre instance when he said that his plan would have $1,000 co-pays. He has claimed repeatedly that Sanders’s single-payer plan would entail “a deductible in the paycheck,” which is not what a deductible is and makes as much sense as a zinger as when he said President Trump is only comfortable in a “mosh pit.” (It would also be great if a debate moderator could ask Biden what he thinks a mosh pit is.)

If we can’t have that, I would implore the moderators to find out why Biden claims his plan would achieve universal coverage, when his own website says it would leave around 3 percent of Americans, or more than 10 million people (roughly as many people as currently get their health insurance from the ACA exchanges), uninsured. You can say one or the other, but you cannot say that your plan is universal while it leaves people out. This is to say nothing of whether insurance is actually affordable and usable under his plan, which should be considered just as important in deciding whether a plan constitutes universal coverage. It is the number one job of any journalist interacting with presidential candidates to ensure that they are being honest, and Biden claiming his plan is universal is the height of dishonesty.

Both Biden’s and Pete Buttigieg’s plans involve reviving some form of the individual mandate; both candidates must be asked more detailed questions about what they have in mind. Biden has previously and explicitly said he would bring back the individual mandate, claiming it would be popular “compared to what’s being offered.” Buttigieg’s plan, meanwhile, involves what The Washington Post recently described as a “supercharged” version of the mandate, where the previously uninsured would be hit with a bill for their “retroactive” coverage on the public option throughout the year, possibly through tax filings. (For someone whose health care rhetoric has centered so squarely on “choice,” this is an interesting position for Buttigieg to take, and one that directly contradicts statements he’s made in the past.)

Buttigieg’s health care proposal hinges on the idea that uninsured people would automatically be enrolled in the public plan, but the campaign has not outlined any actual mechanism for doing this. The government currently does not have a list of everyone who is uninsured. Would they enroll everyone whose incomes came below a certain level, based on tax returns? What happens if they already have insurance? Biden has made similar claims about his plan, asserting that there would be an “automatic buy-in.” This makes no sense—unless you intend to charge people at tax time for insurance they might not know they had. If that’s the case, Biden’s “buy-in” not only makes the Obamacare penalty seem laughable in comparison, it’s also a risibly stupid way to provide health care, not just coverage. A useful question for these candidates would be: How, exactly, is their plan going to automatically enroll the uninsured? And are they prepared for the political consequences of tacking on massive premium payments of up to 8.5 percent of previously uninsured individuals’ income onto a tax bill at the end of the year?

Though she qualified for this debate, Amy Klobuchar is not going to be the Democratic nominee. She is currently polling at around 7 percent in Iowa, eight points below the threshold to get any delegates, and 4 percent in New Hampshire. It would take some kind of bus crash involving several of the other candidates to propel her to victory now, despite the plaintive cries from the centrist pundit class about how sensibly electable she is. Still, with her on stage, moderators could ask an important question: If Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren won the nomination, would she vote for a single-payer bill in the Senate, or would she side with Republicans to defeat universal health care?

Though Bernie Sanders’ single-payer proposal underwent some of the more aggressive early questioning—including every known iteration of “How will you pay for it?”—there is an opportunity to ask useful, granular questions. Debate moderators could inquire as to how he plans to get the votes for single-payer, or get even more juicily specific: How would his single-payer plan determine which drugs and procedures are covered? How could Congress structure the bill to help shield it from the Supreme Court striking down key segments, as it did with the Affordable Care Act?

Elizabeth Warren, too, has weathered her share of the health care questioning—arguably an unfair amount, given the underlying uncertainty of Biden’s and Buttigieg’s plans, which slide by with less scrutiny—but there is yet more for her to answer. Warren’s plan to pass a public option first, and then attempt to pass single-payer in her third year of office, centers on the idea that people will love the public option so much that everyone will push for single-payer. A moderator could ask how she envisions setting up a public option quickly enough that most people are on it (and love it) by 2023. Her recent rhetoric, emphasizing that Americans would have the “choice” to try the public option, raises another question: If that choice is so important, what happens if she does pass Medicare for All in the third year of her presidency, and that choice goes away? If her argument is that people should have the choice to keep their private insurance, some people will do that—and those people might be pissed when 2023 rolls around.

I would bet my KitchenAid stand mixer on none of these questions coming up in next week’s debate. It is far more likely that any section on health care will see more of Biden and Buttigieg being allowed to blithely claim their plans will automatically scoop up uninsured people, or that we will hear, once again, how much people love their private insurance. Perhaps the most important question we could ask candidates might be: How can we fix these terrible debates?