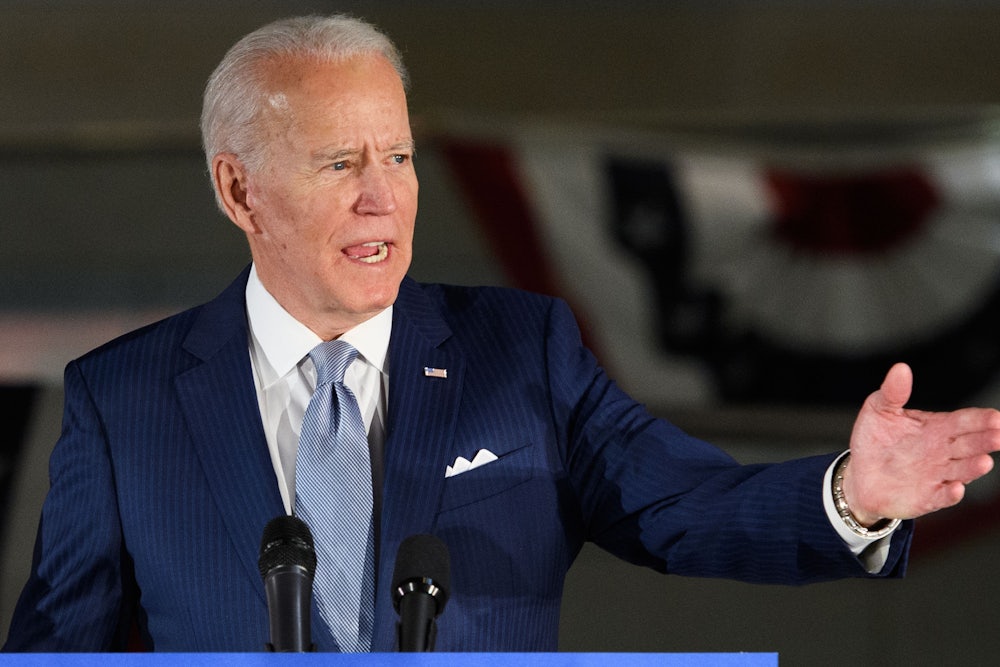

Since Bernie Sanders’s campaign faltered and subsequently folded, the question of what can be done to bring young voters over to the Biden campaign has, somewhat belatedly, been the subject of some worried discussion among the pundits. This outpouring has not yet been matched with much public fretting from the Biden campaign, and much less in the way of policy concessions and outreach to former Sanders supporters. Still, the campaign season is young. Biden has at least said he would like to reach out to Sanders voters, though the initial offering was not much more than some wan rhetoric: “I hear you. I know what’s at stake. I know what we have to do.”

The harsh truth is that Biden and his campaign have likely decided that they can win the White House without doing much work to win over young people, of whom he’s been broadly dismissive for some time. When confronted by young activists with pointed questions about his record, Biden harshly brushed them off, recommending that they vote for “somebody else” or, in one particularly nasty case involving a question about deportations, for Trump. He has dismissed the notion that millennials—a generation that graduated into a recession, never recovered their earnings, and is now facing greater economic impacts from the coronavirus pandemic—have had it tough. “No, no, I have no empathy for it,” he said in summation of a generation’s economic woes, “Give me a break.” To a generation that has sought transformational ideas, a candidate who told his wealthy donors that “nothing would fundamentally change” under his leadership does not carry much appeal. And if Biden has had a change of heart about his brusque treatment of young voters, it’s difficult to discern what he’s doing differently. A bad podcast does not youth outreach make.

So what can the young Americans who were part of Bernie Sanders’s movement reasonably expect to get in concessions from Joe Biden? In reality, not much. They should, however, act as if they can. There are myriad policy areas in which the left could make demands, from climate change to immigration. A collection of advocacy groups, including the Sunrise Movement and Justice Democrats, has already sent a letter to the Biden campaign outlining its demands, which were, for understandable reasons, pretty lofty goals. Nevertheless, the forceful and hopeful approach is the right one. If you want something, don’t ask for nothing.

Medicare for All was arguably the defining issue of the Democratic primary, and Bernie Sanders’s platform was the subject of early disputes between him and Biden. In July 2019, Biden criticized Medicare for All, saying he didn’t want to “start over,” and arguing that Democrats did not have “a hiatus of six months, a year, two, three, to get something done.” That came days after Biden said he opposed efforts by either Democrats or Republicans to “dismantle” the Affordable Care Act. The Sanders camp hit back, accusing Biden of “misinformation” for making the erroneous claim that implementing Medicare for All would create a period in which people would have neither government insurance nor the protections of the ACA. The ensuing months of repetitive debate questions and media brow-furrowing about How to Pay For It ensured that the issue remained perhaps the clearest division between the two candidates’ visions.

It’s unlikely Joe Biden is going to support Medicare for All after vanquishing the Medicare for All candidate. But supporters have good reason to keep the issue in play, even if they can’t wrest a concrete change in Biden’s platform. Throughout the primary process, Democratic voters supported a single-payer health care system—that is, replacing private insurance with government insurance—in all the exit polls that were taken this year. (Proponents of the public option often hit back that their policy polls better and point to polls showing that single-payer becomes less popular if you poll people on common attacks on it, though without acknowledging that similar criticisms of the public option are never polled and that these plans have benefited from the fact that the media has been asleep at the switch at scrutinizing the various public option plans on offer.) The plan that Biden believes to be dangerous and unreasonable is supported by clear majorities of the primary electorate that chose him.

After Sanders dropped out, Biden’s big concession to this groundswell of support for single-payer was a proposal to lower the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 60. Senators not named Bernie Sanders have already proposed lowering the age to 50 or 55. The Democratic Party platform in 2000 proposed Medicare enrollment at 55 for everyone. This is like a parody of a milquetoast Democratic proposal; if he could have worked tax credits in there too, it would have been pitch-perfect comedy.

But the more obvious problem here is that if you are trying to reach young voters, promising they’ll be eligible for health care in 30 to 40 years is not all that motivating. The life experience of young voters has, after all, taught them that “30 to 40 years” is time enough to have two world-altering economic catastrophes, so it reads more like a slap in the face—or a demonstration that the Democratic candidate is hopelessly adrift from the lived-in reality of the electorate. Biden could have proposed to extend Medicare eligibility to young people—people under 26 or even under 18—which, as The Week’s Ryan Cooper pointed out, is cheaper for the government and “automatically creates a constituency for further expansion,” as well as being potentially popular with young voters who shunned Biden.

So what is the least we can ask of Biden when it comes to health care? He has already shown no interest in altering the major structure of his public option plan. The most glaring problem in his plan, one that Sanders should have pressed Biden on far more, is that it explicitly leaves around 10 million Americans uninsured. His own website says the plan will cover 97 percent of Americans, which would leave roughly as many uninsured Americans as currently use the ACA exchanges that underpinned the last big health reform push for which he constantly takes credit. If the left wants something to press Joe Biden on that is both reasonably achievable and worth doing, pushing him to address why he’s proposing to leave any American without health coverage would be clarifying. It would be nice to know, at least, whether he knows that’s what his plan says. No one except Julián Castro seems to have pushed him on it.

Prominent as it was, health care was not the only issue in the primary. The coronavirus crisis promises lingering consequences—tens of millions unemployed and the possibility of a depression—which the next president will have to address. The pandemic has also heightened the visibility of the class divide, between those who can comfortably work from home and those who must continue to put themselves in danger. Grocery store workers are dying. Companies that sell closets and video games have deemed themselves essential, forcing their workers to risk infection and death. Workers at a single Smithfield pork plant in Sioux Falls represented 44 percent of all cases in South Dakota last week: Work performed mostly by immigrants that is punishing under the best of circumstances has become a vector for a deadly virus. The same has happened across the meatpacking industry, and employees at another Smithfield plant alleged the company covered up the number of infections and pressed workers to keep coming in to work.

Sanders’s proposal to force large companies to share profits with their workers and give them 45 percent of seats on their boards is popular with voters. However, Biden will likely be heeding the call of his well-heeled donors, who would not be at all keen to see profits so widely shared among the common people. Still, the left could press for more from Biden on how he would protect workers. As Hamilton Nolan recently noted, Biden’s first presidential fundraiser was co-hosted by Steve Cozen, co-founder of Cozen O’Connor, a law firm that represents companies trying to squash their unions. In December, Biden’s campaign said it had raised at least $25,000 from Cozen, and a Center for Economic and Policy Research analysis from January found big donations to Biden’s primary campaign from more than 10 other employees just of Cozen O’Connor. This is not compatible with Biden’s supposed promise to go after union-busting firms more aggressively, even pledging to hold executives who intentionally (as opposed to unintentionally?) interfere with union activity criminally liable. If Biden wanted to show he was serious about this promise, he could return donations from union-busting lawyers and promise to at least study plans for worker ownership.

The problem of Biden’s donors and bundlers goes beyond Steve Cozen. Biden has raised money from all sorts of unsavory people; one of his top aides is a former lobbyist for a number of drug companies and the American Hospital Association. Unlike Sanders, Biden simply does not seem to see the problem with allowing lobbyists and plutocratic interests to worm their way inside his campaign. As Sam Adler-Bell and David Segal argued, Biden merely making policy promises is not good enough; he must also commit to installing personnel the left can trust to implement these ideas. At the very least, he could return donations from lobbyists right now. This is something that, sadly and incredibly, falls into the category of “too much to expect” for voters who’d like to see less corruption in high places. In the interest of meeting even lower expectations, Biden could acknowledge the mistakes that the Obama administration made in lobbying reform and pledge to end the revolving door. He clearly won’t disavow his super PAC, something even Elizabeth Warren couldn’t manage to do; he could, however, promise not to hire anyone who has donated to it.

There is one policy that would be a minor gesture that would nevertheless have a great impact: Legalizing cannabis. It’s a silly stereotype that young people can be motivated to get out to the polls just by promising them legal weed, but it could help at least a little, and the change that Biden would need to make to his own platform would be so minor that there’s no reason not to. Biden has previously said both that cannabis needs to be “basically, legalized,” and also that he is “not prepared to [legalize] as long as there are serious medical people saying, ‘We should determine what other side effects would occur,’” at the same event. Months before, he described marijuana as a gateway drug. So to say that Biden’s position on the drug is a little unclear is an understatement. He could reach out to young voters (and those who care about the persecution of people of color under the guise of the war on drugs) by firmly stating that he, like Bernie Sanders, would legalize cannabis as soon as he took office. He doesn’t need to pretend he loves High Maintenance or attempt to offer an opinion on the best kind of vape pen to do this; but there’s no reason in the world why Biden’s position can’t be as progressive as Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker’s.

All of these criticisms, questions, and proposals, which barely scratch the surface of the problems with Joe Biden as a candidate and as a leader, are reasonable and mild. They are relevant and pressing questions that affect whether the young are able to afford to have children, or to retire, or die of old age instead of climate change. It’s a middle ground on which Biden and these voters can reasonably meet, without harming Biden’s chances against Donald Trump in any way. The left’s power grab failed, and the demands for justice and equality that the Democratic Party has long considered unreasonable won’t be met. Now we will find out if the party would meet reasonable demands, or if it’s determined not to listen to the voters who comprise its future base at all.