In 2003, writing a concurrent opinion in United States v. Lara, a case that determined an individual can be charged with the same crime in tribal and federal court, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas described the contradictory nature of federal case law as it relates to Indigenous policy: “In my view, the tribes either are or are not separate sovereigns. And our federal Indian law cases untenably hold both positions simultaneously.” This week, nearly 20 years removed from Thomas’s assessment, the high court’s institutional inability to grasp the basics of tribal sovereignty was once again on full display.

On Monday morning, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in McGirt v. Oklahoma, a case concerning whether the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s 1866 treaty reservation boundaries are still legally in place. The MCN reservation was never officially dissolved by Congress, meaning that a large swath of what is now Oklahoma, formerly Indian Territory, is still technically under MCN jurisdiction, even if it is effectively governed by the state. The appealing party, Jimmy McGirt, is currently serving a life sentence for sex crimes he committed against a child. The case is not concerned with his guilt, which was well established, but rather the jurisdictional issues that arise from the fact that McGirt’s crimes were committed on what is still technically MCN land, but he was tried in state court. (Typically, federal courts have jurisdiction over major crimes committed on sovereign Native soil.)

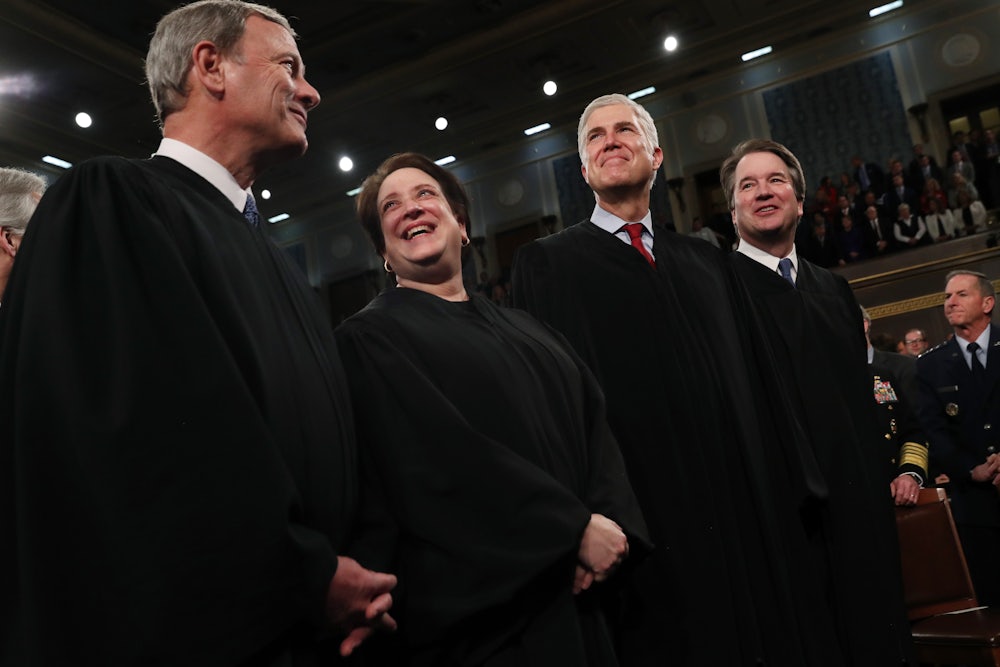

The issue was initially argued in Murphy v. Carpenter last spring, but because Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, had heard the case when he was sitting on the Tenth Circuit, he had to recuse himself, leading to a 4–4 split. Seeking to bring in Gorsuch to answer the question definitively, the court took on McGirt, which quickly became one of the most intriguing tests of the United States Indian Country legal framework in recent memory. Listening to the arguments, as the public is now able to do because of the pandemic, it was clear that most of the justices had a staggering but sadly unsurprising lack of knowledge on the basic tenets of sovereignty and Indian Country.

The typical partisan lines that get drawn around other political, social, and legal issues in America are completely upended when it comes to matters of Indian Country. (Which is why I found myself, in a strange moment of dissonance, nodding in agreement with Thomas’s 2003 comments and would later find myself smiling at the comments of a Trump appointee.) And this week, as the arguments went along, it became increasingly clear that, of all the justices on the bench, it was Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Brett Kavanaugh who stood out as particularly misguided on the matter of tribal sovereignty.

Ginsburg repeatedly asked about the practical effects of ruling in favor of McGirt and the MCN, citing concerns that hundreds of cases would have to be retried in federal court because they occurred on Native land. This is one of the arguments made by the state of Oklahoma in its briefings, but in a recent analysis of the cases that would potentially need review in The Atlantic, Cherokee Nation journalist Rebecca Nagle argued that these fears are wildly overblown. After filing an open-records request, Nagle wrote that, “While Oklahoma seems to count all 1,887 inmates, or something close to that, in its warnings to the Supreme Court, our research showed a small fraction—fewer than 10 percent of the cases we investigated—would actually qualify for a new trial.”

(To Ginsburg’s credit, she did eventually come around, asking a question to the federal attorney about why tribally held land should be held to a less stringent standard for disestablishment than lands held by the United States. Ginsburg’s point was to contextualize the history of allotment and the creation of Oklahoma as a state, which happened without an express disestablishment of MCN’s reservation by Congress.)

Kavanaugh, for his part, was laser-focused on the racial demographics of the population within the MCN reservation at the time of Oklahoma’s statehood, pointing out that it was 60 percent white in 1890. (He was far less interested in acknowledging that this came about due to hordes of Americans illegally moving into Indian Territory to steal Native land.)

“By 1890 you have an odd situation of an Indian territory, nominally, that is predominantly white. The options of Congress at that time are to remove the whites or remove the Indians—neither of those would happen,” Kavanaugh said. “The other remaining options were tribal government over non-Indians, which is contrary to tradition, or to create a new state. Congress chose the new state option … I wanted to get that history out there because I think we are talking about Indian territory and reservations when it was 60 percent white, 10 percent Black, and 30 percent Indian in the relevant territory.”

This is especially dangerous, as race-based arguments are the weapon of choice for conservative opponents of Indian law. While blood quantum laws still exist for a variety of confounding reasons, citizenship of a given Native nation is not based on race but on political distinction. The race-focused argument continues to be employed by opponents of the Indian Child Welfare Act and was a key point in the infamous Oliphant case, which now prevents Native nations from trying and punishing non-Natives when crimes are committed on sovereign Native land and is a major contributing factor to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis.

In question after question, it was clear that the justices were primarily focused on how the non-Native people within the reservation boundaries would feel if the case came down on the side of MCN sovereignty, not on the matter of sovereignty for MCN citizens. “What would you say to those people, if we decide this case in your favor?” Justice Samuel Alito asked Riyaz Kanji, the MCN attorney. “Would they be surprised to learn that they are living on the reservation and that they are now subject to laws imposed by a body that is not accountable to them in any way?” Kanji replied that Alito’s concern would be moot, as state courts would still have jurisdiction based on past Supreme Court rulings.

This inquiry is nearly the exact same insulting line of questioning that Representative Tom McClintock, a Republican from California, raised last fall during a hearing on a bill that would allow the tribal law enforcement to prosecute non–tribal citizen offenders for crimes including sexual assault, sex trafficking, and stalking. He imagined a hypothetical situation in which a non-Native tribal casinogoer sexually assaulted a casino employee and would then be forced to answer to the courts of the sovereign nation. He described, in other words, how laws work, except he presented it as an outrage.

To follow up on the point Thomas was trying to make in 2003, Indian law is messy and complicated in large part because the U.S., for its entire history, has crafted and recrafted its laws to fit its pursuit of Native land, regardless of conflicting legal precedent or treaties. But if one is to read Murphy and McGirt straightforwardly, without overly concerning oneself with the limited practical effects, the through line is ultimately quite simple: Congress never explicitly disestablished the MCN reservation and now, a century after the U.S. set out to systematically steal the land of the Oklahoma tribes and assimilate their people, tribal attorneys are finally in a position to take action on the colonizer’s oversight.

This was the approach of Justice Neil Gorsuch, who established a history of hearing and ruling favorably on Indian Country cases when he sat on the Tenth Circuit. Gorsuch on most any other issue could be described with a number of unkind terms. But on matters of Indian law, he has repeatedly recognized this country’s violent history and contradictory legal rulings and has stuck to the Constitution’s determination that treaties are the “supreme law of the land.” And so on Monday, it was Gorsuch, not the liberal justices, who seemed to best understand and articulate the contours of the sovereignty issue at stake.

“In the briefs, you make a lot of later demographics and evidence about what happened—I guess I’m struggling to think why that should be relevant in an interpretation of statutes from the last century,” Gorsuch said to the Oklahoma attorney, essentially pointing out that the state’s focus on the reservation’s demographics were more a distraction tactic than a constitutionally sound argument. “Especially when later demographic evidence sometimes shows nothing more than that states have violated Native American rights, including Oklahoma’s enforcement of its state laws on tribal lands against tribal members in the past.”

It’s a sucker’s bet to try to predict an outcome here, so I won’t. But the public nature of the questioning did expose how unfamiliar the majority of the justices are with Indian law and basic history. And like so many other non-Native people, their focus constantly lingered away from the American theft of Native land and abandonment of treaty rights. Gorsuch aside, the justices did not spend their limited time wondering what the ramifications of this violence have meant for generations of MCN citizens; instead, they found themselves repeatedly debating how a ruling in favor of a Native nation would affect non-Natives. It’s not a shock. This is how it’s always been. But given that these nine people are the ones entrusted with meting out justice for all of America, including Indian Country, it’s still more than a little disappointing that so little has changed.