In the days immediately following the publication of the not-exactly-positive review of Netflix’s Emily in Paris I wrote for this very website last October, friends and strangers alike had one burning question: Had I watched the other Parisian, media-centric comedy on Netflix, Call My Agent, which was set at a chic agency for actors and directors? It was authentically, actually French, instead of cod French, they all said; it was genuinely funny, and the characters with “style” dressed stylishly, and nobody said anything about their “coq” or mistranslated the word “ringarde.” In addition, it had cameos from many major actors, playing themselves: Juliette Binoche tumbling down the stairs at Cannes, or Monica Bellucci bemoaning her perpetual singledom, or Béatrice Dalle furiously storming out of a gratuitous nude scene and then hiding in a convent. Isabelle Huppert stayed on for two full episodes in the third season, sending up her reputation as a workaholic, which if you are a TV show about actors is a flex roughly equivalent to that of getting Jesus to sign on for a two-episode arc in your Bible epic. It was gentle but sophisticated, clever but not taxing, low-stakes enough to be soothing but well written enough to ensure that you were always thoroughly invested in its principals—the leonine, ruthless Mathias; the fey and hilarious Hervé; the bumbling, hirsute Gabriel; the chic and horny and ambitious Andréa; et cetera, et cetera.

Everything they said, it turned out, was correct: Call My Agent is a gem, a rare amalgam of elegance and real heart that coaxes belly laughs out of its film industry setting not by lampooning the vapidity of the movie world but by lovingly poking fun at its characters’ passion for their chosen field. Harebrained schemes are hatched in order to ensure the right actors end up with the right directors, the work’s quality infinitely more crucial than its budget; double-crossing is accepted, grudgingly, if it turns out to be about integrity rather than money. “You have always been ruthless, stopping at nothing,” Mathias’s lover Noémie tells him, with a straight face, “but it didn’t stop me from falling in love with you, because I saw you did it out of artistic conviction.” The people who work at Agence Samuel Kerr are “competent (even when they fall victim to disaster), competitive, and devoted,” Alexandra Schwartz wrote at The New Yorker in 2018. “They love what they do, and they revere the cinema. That, and the fact that business and pleasure mix very freely, is how you know that the show is French.”

If its quintessentially French qualities do not exactly seem like probable attributes for an international hit—audiences outside of France, for instance, may not immediately recognize some of the actors who do cameos as themselves, unless they happen to be very well versed in the French New Wave—they are also precisely the thing that viewers have seized on, hungrily and happily, as the source of its appeal. Satires of Hollywood, especially those set in L.A., are often either cruel or sour, zeroing in on the industry’s rampant vice and avarice, its plastic sheen. Call My Agent, which does not contain even a single joke about a needlessly specific latte order, breaks the mould in order to suggest that movies might, in fact, be as serious and important as real life.

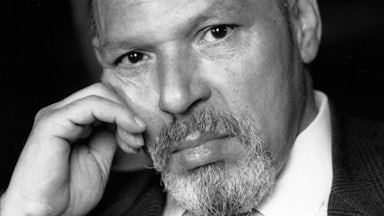

The show’s breakout star is Camille Cottin, the impossibly soignée middle-aged actress who plays Andréa Martel, and who somewhat improbably first rose to fame as the presenter of a prank show whose name, Connasse, is an expletive. For a character in film or television to begin their arc as a seductive, selfish womanizer with a phobia of monogamy and end it married to a sane and serious woman is not unusual or innovative; ditto a transition from seductive, selfish womanizer with a phobia of parenthood to goggle-eyed, devoted parent. It is unusual and innovative, though, if that character is female. For three seasons, viewers have watched as Andréa—a kind of cross between a lesbian Serge Gainsbourg and a fashion editor, a prolific shagger and inveterate partier who at one point could not remember whether she had recently had sex with more than one woman named Clementine—shocked herself by falling slowly, inexorably in love with a shy and uptight accountant named Colette, then by becoming not only a wife but a new mother.

Whereas some shows might have employed this storyline to bludgeon viewers with an old-fashioned, didactic message about the superiority of the nuclear family over the more shifting pleasures of deliberate, carefree promiscuity, Call My Agent treats Andréa’s new and old lives with the same degree of reverence—her move from putain to maman changes her schedule and her sex life, but it does not change her style. She negotiates her daughter’s place at a particularly bougie daycare as if she were trying to sell one of her actresses to Claire Denis or François Ozon. That her neat tuxedo jacket now comes with a pale, unglamorous splash of vomit on its collar still does not negate her poise.

Season four, which launched this week, is in many ways exactly what a faithful viewer of Call My Agent might expect. Its first episode, in which a very funny Charlotte Gainsbourg tries to get out of an amateurish, dreadful sci-fi movie by pretending to have injured herself slipping on a stray banana skin, perfectly demonstrates the series’ broad appeal—it has enough in-jokes to convince movie lovers that they’re being catered to and enough witty, breezy moments to keep anyone who is not as interested in gags about the oeuvre of Lars von Trier on board for more. (“How am I supposed to know if it’s a good script?” Gainsbourg ponders. “I signed on for Antichrist!” “I loved you in Nymphomaniac,” a scruffy prop department lackey tells her, later, the compliment hanging creepily between them for one subtle, perfect beat.)

Through a storyline in which Andréa and Colette are struggling in the immediate aftermath of their domestic happy ending, however, the new season gradually reveals itself to be about a very different kind of love—one unrelated to monogamy or marriage, unaffected by familial ties, and only very slightly touched by sex. I am, of course, referring to the love experienced by cinephiles for cinema, a passion next to godliness in its devotion, and adjacent to actual, romantic love in its tendency to make those experiencing it speak in embarrassing, declarative statements. When Andréa informs Colette that she is trying, desperately, to make time for her family, and Colette asks: “Which family—ours, or the great family of cinema?” the line ought to be toe-curlingly pretentious. In the context of the show, it is a legitimate question. More than ever, Call My Agent is concerned with one particular and very French dilemma: Is it possible to be a functioning person, and especially a parent, in addition to being a die-hard, full-time advocate for the importance of the arts?

When Andréa admits to Colette that she knows she never hesitates when trying to please her clients in the same way she occasionally does when tasked with coming home on time to see her child, Colette admits she is as moved by her wife’s honesty as she is saddened by her statement. We are not asked to see Andréa as monstrous—or if we are, it is in reference to the phrase coined by the writer Jenny Offill in her 2014 novel, Dept. of Speculation, “art monster.” “My plan was to never get married,” Offill writes. “I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things.” If Andréa does mundane things, it is so that Jean Dujardin can make what she believes will be a brilliant new movie, or to prevent Jean Reno from retiring altogether. What is wonderful about her journey in this latest season is the way that she begins to realize that the act of bringing up her daughter is not actually that different from the work she does at ASK, in the sense that both tiring, self-sacrificing demonstrations of her love will ultimately end in something bigger, more beautiful, more enriching.

It is never less than pleasurable to watch Andréa grapple with the ropes of being human, in the same way it was always pleasurable to watch her chasing her beloved actors around Paris in previous seasons, playing at being a therapist or a chauffeur, a matchmaker or confidante. The camera, loving as it does a singular and striking face, adores Cottin as much as Andréa loves her clients: her elongated, Modigliani cheekbones, the tremendous Roman nose that juts out like a questing ship’s prow or a shark’s fin, sleek and urgent. It surprised me to discover that she played the lead role in the French reimagining of Fleabag, given that she lacks the very qualities so beloved in its heroine as played by Phoebe Waller-Bridge—she’s amusing but not goofy, uninhibited but not undignified, scarcely a natural underdog. Like the show itself, what she possesses is an unusual balance of humanity and hauteur.