The grinding quality of American presidential memoirs owes to the cross-purposes they serve: to deliver a point-by-point defense of the administration’s record, while trying to persuade the public that their departed leader was indelibly, even endearingly, human. Obligatory features include mischievous tales of bucking White House protocol; an extended homage to the presidential predecessor who was a fine man on a personal level; a printed extract of a letter from a constituent or child reassuring the president that he should regret rien; and shout-outs to sundry staff and swamis, whose capsule biographies expand and contract in proportion to their fealty.

If Ulysses S. Grant’s memoirs became an accidental modernist classic, it was because he evacuated his own personality so completely from his account that he figured as another instrument of war. Barack Obama’s A Promised Land is somewhere at the opposite end of the spectrum. The expectations for the book recall the expectations for his presidency. Obama is aware of this and aware that his ability to report on the progress of his self-awareness was always part of his appeal. Addressing a crowded hall at the New York Public Library in the postelection haze, Zadie Smith proclaimed Obama an evolutionary advance in the history of democratic representation: “This new president doesn’t just speak for his people. He can speak them.” Two years into his presidency, the head of the Harvard history department declared, at book length, that Obama was a Pragmatist philosopher king, who had planted the torch of John Dewey and William James in the Oval Office. Not to be outdone, a leading sociologist at Yale claimed that the president was his own social movement.

Compared to the and-then-we-became-buddies volubility of Bill Clinton’s My Life, and the point-blank basicness of George W. Bush’s Decision Points, Obama’s A Promised Land is both a more disciplined and ambitious undertaking. It could have been titled “The Education of Barack Obama,” if that didn’t suggest a few more degrees of irony than he is willing to allow. Obama tends to believe he made the best of each of the quagmires he inherited. Accompanying his exculpatory agenda, there is an edifying one: The memoir is aimed at young idealists, whom he spoon-feeds background history, from the rise of Putin in Russia to the story of Saudi oil.

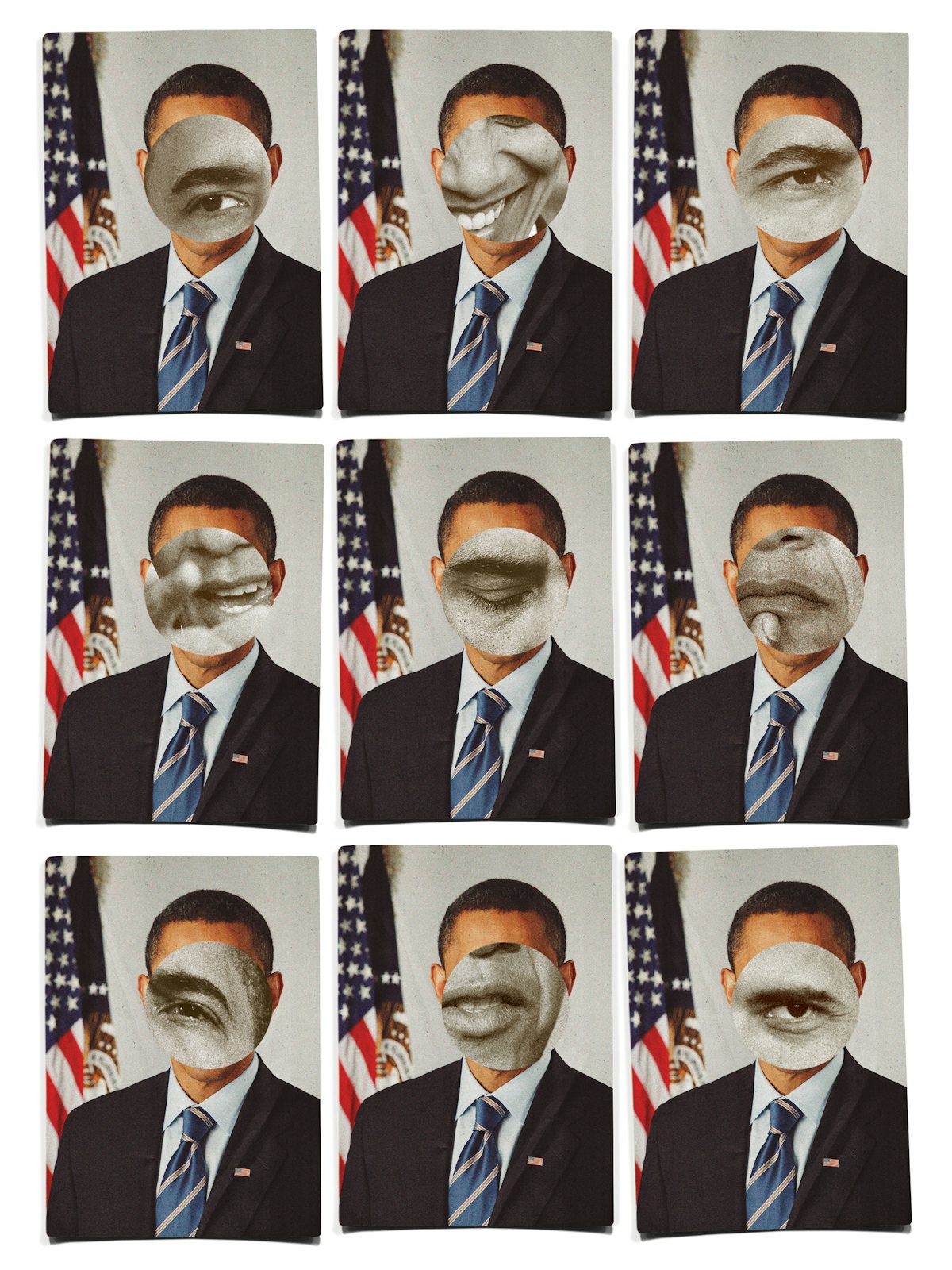

The smoothness of narrative benefits from the fact that Obama sees his political ascent as inextricable from his own individual narrative. Early in the book, he divides himself into a series of stock characters: the Frank Capra Obama who comes to Washington “starry-eyed” (foil: Rahm Emanuel); the wised-up Philip Marlowe Obama who gets all the best lines as he tries to steward the status quo (foil: the irrepressible paladin, Samantha Power); and the Jack Ryan man of action determined to deliver on his ideals (foils: David Plouffe and Reggie Love, who bear witness to the force within him). Despite being more thoroughly the work of a single hand than its predecessors, the strange experience of reading this presidential memoir is that it feels more storyboarded: more crisp, more conventional, more strategic, more Netflix-series friendly.

Capra Obama occupies the opening portion of A Promised Land. There is ample evidence that Obama was a complicated young man, not only as relayed in his 1995 memoir, Dreams From My Father, but also in letters that emerged later, written in his college years, when he coldly registered the limits of “bourgeois liberalism.” Any access to this countercurrent has been shut off in the first part of A Promised Land, in which Obama talks of his youthful patriotism. “The pride in being American, the notion that America was the greatest country on earth—that was always a given,” writes Obama. “As a young man, I chafed against books that dismissed the notion of American exceptionalism.” Likewise, he began to see himself less as an inheritor of the civil rights struggle but rather its culmination and fulfillment. Black people of a certain age, he writes, “now recognized in me some of the fruits of their labor.”

After college, Obama moves to Chicago to become a community organizer, where he warms his hands on the embers of the civil rights movement, and believes he grasps the limits of Harold Washington’s original “rainbow” coalition. “Maybe there was another way,” he writes. “Maybe with enough preparation, policy know-how, and management skills, you could avoid some of Harold’s mistakes.” A different future unfurls before him. Obama meets the rusted language of class solidarity with gleaming paeans to self-actualization. “Maybe the principles of organizing could be marshaled not just to run a campaign but to govern—to encourage participation and active citizenship among those who’d been left out, and to teach them not just to trust their elected leaders, but to trust one another and themselves.” This is almost exactly what did not happen when Obama became president. Once he assumed office, Obama’s meticulously constructed campaign booster rocket fell away. He began filling the ranks of his administration with Clintonite apparatchiks. Although it can be tempting to blame this continuity on Obama’s inexperience or opportunism, it was perhaps more the result of having assumed leadership over a party that was so ideologically barren that it could not sprout a bureaucracy that was anything more than a tumbleweed of status-quo technicians.

The main antagonist for Capra Obama is not any Mr. Potter but his own demons. At first, he wonders if it is even ethical to attend law school, until his mother sanctions his decision to go. At every station on his pilgrim’s progress to the White House, he relates that he was gnawed by self-doubt. “Was it just vanity? Or perhaps something darker—a raw hunger, a blind ambition wrapped in the gauzy language of service?” he asks himself when, as he is deciding whether to run for president, a voice pursues him, whispering “No, no, no.” The authenticity of such a scene is beside the point. Why does Obama feel the need to dramatize what other presidents take more or less as a given? It seems to stem less from any genteel desire to conceal ambition than to dramatize his political rise as a morality play in which idealism vanquished vanity. Such a staging partially obscures the other factors of Obama’s ascent: his luck, his uniquely advantageous position in the meritocratic elite, and—perhaps most crucially—the broader context of a Democratic Party and union sector that had been lobotomized by Clintonism, which made wagering on an individual savior seem worth the gamble.

How does Obama conquer his doubts? The scene is telling. When Michelle asks him, in front of his staff, why he needs to be president, Obama launches into a full-Capra mini-speech about how kids around the country, Black, Hispanic, or just plain awkward, “will see themselves differently.” The reader expects this sentimentalism to be swiftly subjected to severe inspection. With Black wealth having cratered across his two terms, how much did the kids get to do with their personal epiphanies? Instead, the camera pans back to Michelle: “Well, honey, that was a pretty good answer.”

The same format replays when Obama wins the Nobel Peace Prize. Early in the morning, Obama learns he’s won the prize. “For what?” he asks, with winning self-deprecation. Michelle, winningly as well, acts as if he’s just found a toy in his cereal. But when the camera finally gets to Oslo, Obama has imbibed the hype. Looking down from the window at an assembled crowd of adoring Norwegians holding candles, Obama makes a kind of peace with his savior status. The voices return: “Whatever you do won’t be enough,” I heard their voices say. “Try anyway.”

The electoral gods smiled on Obama when it came to higher office. In 1996, he ran unopposed in the Democratic primary for a seat in the Illinois state Senate, while in his 2004 run for the U.S. Senate, his Republican rival collapsed in a sex scandal. Less commonly cited, but no less remarkable, was the change in Democratic primary rules for proportional voting that allowed Obama to defeat Hillary Clinton for the nomination in 2008. In the campaign for the presidency itself, Obama faced down an opponent who was convinced he could be forgiven for economic illiteracy in the midst of an economic recession. He also had other winds at his back: Colin Powell had been floated as a plausible “moderate” Black candidate some years before, and, more acutely, the popular energy generated by Bush’s Katrina response and Iraq War—the second ignited some of the largest protests in recorded history—would propel anyone into the White House who knew how to harness a modicum of it.

Marlowe Obama comes into focus as he settles into the White House. The case before him is a tough nut to crack. “Resolving the economic crisis—not to mention winding down two wars, delivering on healthcare, and trying to save the planet from catastrophic climate change—was going to be a long, hard slog,” Obama writes. “I don’t want a bunch of happy talk from my supporters,” he gruffly tells an aide. “Goolsbee,” says Obama, addressing his chief economist, “that’s not even my worst briefing this week.” “So what ideals have we betrayed lately?” was Obama’s standard greeting for his humanitarian in chief, the U.N. Ambassador Samantha Power.

This is Marlowe Obama: cool, wry, smoking (on the sly), attuned to “the world as it is,” in the ever-enlisted spin on a V.S. Naipaul line that became the mantra of the administration. The worldly art of compromise begins before he’s president: Hillary Clinton joins as secretary of state, not because of Obama’s needs to appease the Democratic Leadership Council faction of the party, but because, he implausibly claims, she was simply “the best person for the job.” Bill Clinton himself is literally rolled out in front of the cameras when Obama needs to sustain the Bush tax cuts. But Obama suggests that most of his appointments were designed to serve as counterpoints to elements in his own character. Amid this team of courtiers, Joe Biden comes off better than most: one of the more willing to step off the treadmill of war, and a ruling-class realist who does not mystify bipartisanship as an ideal, but sees it as a trusted method for maintaining power.

A curious aspect of A Promised Land is the way Obama intermittently feels the need to defend himself against his critics. It hardly seems lost on him—no stranger to the academy—that future histories of his administration will be written by a younger generation of scholars well to his left, who may be less forgiving of his record as his aura dissipates. Obama’s response to the financial crisis will take center stage in any historical judgment. In his account, Obama toggles between two defenses: first, that he did everything he could; second, who said he ever had a radical agenda in the first place? There is a scene where Marlowe Obama gently mocks a group of bankers visiting the White House before entering on a reverie of his grandmother, a mid-level banker of the Protestant-work-ethic variety. But the main argument Obama makes is that while it would have been tempting to break up the big banks and wreak vengeance on Wall Street, such passions would have upset capital markets. Everything would have been worse for almost everyone. It was not a chance for foundational rethinking, but a time for tinkering. Even if Obama were correct that a financial crisis was not the most propitious moment to challenge Wall Street’s veto over American society, he made no attempt to integrate his response to the crisis into a wider strategy to dislodge that veto at any point in the future.

Obama accuses his critics of basking in the easy conspiracy theory of elite bankers plotting against Main Street. But reading along, one begins to wonder whether conspiracy theories are in fact always a hindrance in a democratizing society. Abraham Lincoln, as Seth Ackerman has pointed out, exhibited something like the “paranoid style” when it came to America’s slave owners, whom he depicted as a “slavocracy” cabal, pulling the strings behind the scenes of government. Obama’s confrontation with the financial elite is revealing. When the administration readies to get behind the Volcker Rule—a minimal piece of legislation that required banks to be more capitalized—Obama wonders whether the public will appreciate the subtle rule change. “They don’t need to understand it,” replies Robert Gibbs, his press secretary, who went on to fulfill the same role for McDonald’s. “If the banks hate it, they’ll figure it must be a good thing.” Much of the essence of Obamaism is captured in the democratic contempt of that sentence: a watered-down regulation (already now rolled back), hyped into “change we can believe in,” and passed off as red meat to the howling masses.

Jack Ryan Obama surfaces later in A Promised Land, mostly in the domain of foreign policy. “Last time I checked this is America,” Obama informs Rahm Emanuel, during the controversy over building a mosque near Ground Zero in 2010. “I’m working on it,” he tells Michelle when she asks whether he’s saved the global tiger population. Despite having to bat away humanitarian interventions like unwanted canapés at a cocktail party, Obama nevertheless did take the bait on Libya. It will be interesting to see whether he revisits the results in the second volume of his memoirs, but his version of the bombing of Benghazi already reads as if he is hesitant to mouth the propaganda himself: “According to Samantha [Power], it was the quickest international military intervention to prevent a mass atrocity in modern history.” This is the secondhand spin in which he indulges for the initiation of mayhem across the Sahel.

When Obama turns to climate change, he affords himself a heroic scene in which he surprise attacks the Chinese premier (“You ready for me, Wen?”) and bullies assorted leaders from India and Brazil into a preliminary understanding about climate controls. “I gotta say, boss,” declares one of the president’s aides, “that was some real gangster shit back there.” But the pièce de résistance of Obama’s foreign policy—the chapter for which Obama is under no illusions that many people will buy his book—is the killing of Osama bin Laden. In a granular last chapter, Obama summons all of his storytelling skills for the account of how a country with a $934 billion military budget managed to kill a Saudi billionaire in his house in the middle of the night. “I’d decided to get in a quick nine holes of golf with Marvin [Nicholson], as I often did on quiet Sundays,” he writes, “partly to avoid telegraphing anything else being out of the ordinary and partly to get outside rather than sit checking my watch in the Treaty Room, waiting for darkness to fall in Pakistan.” As the writer Caleb Crain noted at the time, there is something unseemly about the targeted killing of one man receiving the narrative attention that was formerly accorded to achievements like the Apollo space program.

In the wake of the Fort Hood shooting and the Christmas underwear bomber early in his first term, Obama was acutely sensitive to the costs of failing to fulfill his oath to protect the homeland from foreign attack. Drone warfare and the drama of bin Laden’s assassination were understandable attractions for him. But once again, as in the case of the financial crisis, Obama was less interested in working toward a structural reordering—ending America’s endless wars—than in finding ways to make them less conspicuous.

What is perhaps most disappointing about A Promised Land is how much Obama submits to a prefabricated media narrative. Almost all the minor media flare-ups of his years in power are compulsively tended to. Rick Santelli’s Tea Party tirade from the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange; the beer summit to smooth the feathers of Henry Louis Gates Jr. and the police officer who arrested him; Michelle Obama saying she was proud of America for the first time when campaigning for her husband; Obama’s declining to wear an American flag pin: Each of these picayune moments gets its inordinate due.

It underlines how little Obama tilted at his times, how much he was trying to conserve rather than spend the once-in-a-generation political capital that had attached to him. The tired phrases of the 2000s reappear across his language: “feeling ownership over a decision,” “disruption,” “allies,” “optics,” “running a good process,” “unleashed the potential.” But to move with the time appears to have been the point. As his law school professor Roberto Unger has recalled, Obama was “conventionally smart” with “a cheerful, impersonal friendliness with an inner distance.” In A Promised Land, Obama positively cherishes his ability to project conventionality. “I realized this was now part of my job: maintaining an outward sense of normalcy,” he writes, “upholding for everyone the fiction that we live in a safe and orderly world.” If so, then mission almost accomplished. Readers will have to wait for the second volume for the presumed scene where Obama calls up Buttigieg and Klobuchar (full Jack Ryan mode) and gets them to rally the wagons around Biden.

To his credit, in this volume, Obama does register that something went wrong. “I wonder whether I should have been bolder in those early months, willing to exact more economic pain in the short term in pursuit of a permanently altered and more just economic order,” he writes about the economic crisis. In post-book interviews, Obama has gone further, wondering aloud, like a character who has begun to sense a fourth wall: “I think there was a residual willingness to accept the political constraints that we’d inherited from the post-Reagan era.” His self-awareness in this department may continue to wax. Rather than sifting over decisions Obama could have made differently—the handrails he installed for American inequality, his deportation bonanza, the chain-smoked drones—it may be better at this point to dwell on how Americans came to believe they needed such a savior.