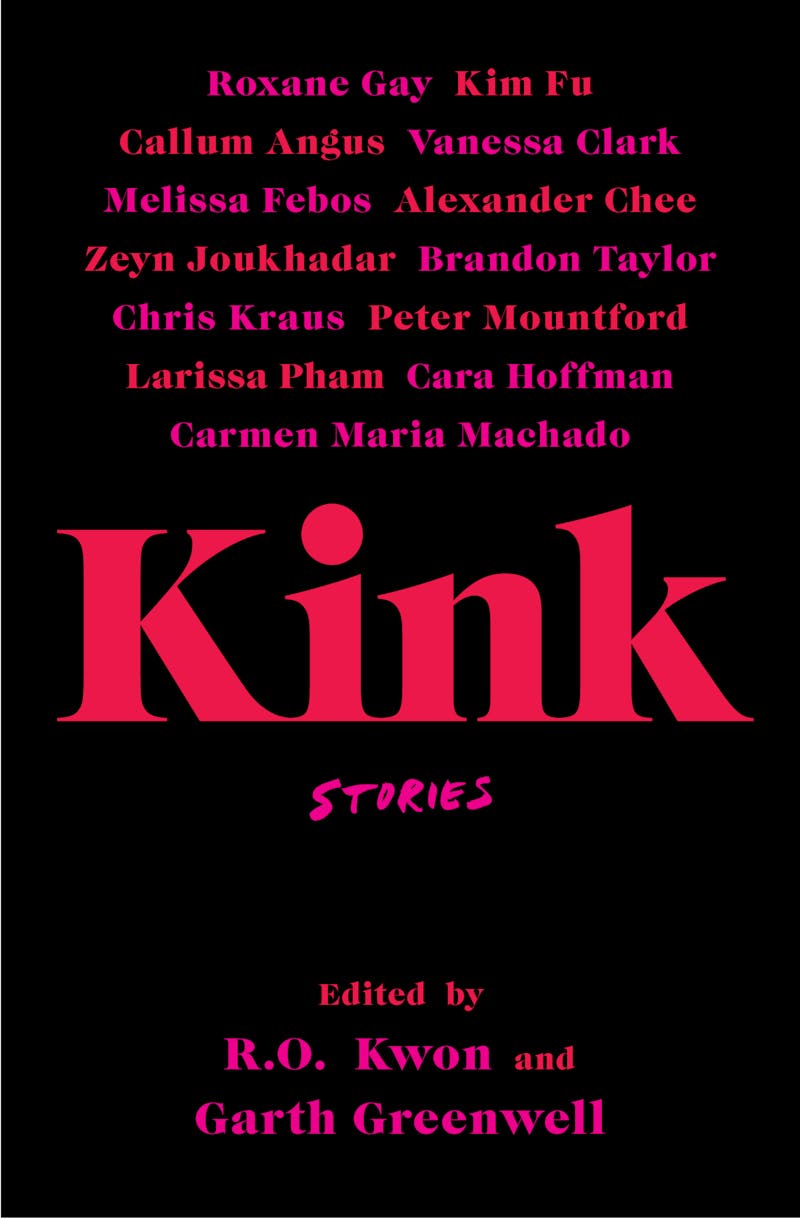

Kink is a new collection of short fiction edited by the novelists R.O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell, including contributions from both. It’s a tasting menu of real variety, with flogged bottoms and lust-drunk tops mingling with vanilla straights nervously trying out their first slap.

The title is the theme: kinky sex. Roxane Gay’s story “Reach” is a delicate recipe for domination, for example, its narrator lingering over details like chopping onions before fucking her partner “over the kitchen counter so that she can taste their bite and cry without cause.” In Zeyn Joukhadar’s “Voyeurs,” a neighbor spies on a suburban queer couple having sex, transforming himself into the freak, despite claiming to find them disgusting and abnormal.

There’s delight in Kink’s sensory abundance, the same way a buffet delights more than a menu. The more you read, however, the less the stories have in common. “Kink” shows itself to be a relative concept rather than a simple noun, referring to whatever seems unusual or strange at any given time in a sexual culture. It covers all kinds of practices and goes by all kinds of names, making “kink” a word we use to group phenomena according to a negative: Kink is the absence of the normal, not the presence of something concrete.

Kink’s introduction sidesteps the problem of defining its own title by using an example. Kwon was reading Greenwell’s story “Gospodar” while on a residency, she explains, and thought it might be a good idea to create a whole collection of this sort of thing. (“Gospodar” is about a BDSM—Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, Sadism and Masochism—encounter that spills into regular old sexual violence, and is handily included in the volume.) Greenwell agreed, and the book now exists.

That it’s easier to refer to a story about the concept than it is to define it outright bespeaks the maddening difficulty of representing sex in words accurately, let alone elegantly. This conundrum also lays bare our heavy reliance on fiction to describe and taxonomize what sex means for the human experience.

Take Gavin, protagonist of Peter Mountford’s contribution, “Impact Play.” He’s a curator of fine art in Seattle who has just left his sexually conservative wife for a future of kinky romance with a new girlfriend, Pilar. She’s a goth who wears a locked metal collar and cuff to signify Gavin’s ownership of her and makes gravestones for a living. They have bruising and rewarding sex, meeting needs Gavin has only just awoken to possessing.

But Gavin is afraid to be seen with her. He’s afraid that his colleagues will find out about the new relationship and he’ll get passed over for promotion—not because he cheated on his wife, but because he fancies a goth. They might think his discriminating eye for art has been compromised, that he’s been dragged into a subculture whose visual values are at odds with high-end curatorial work.

When he and Pilar attend a kink convention in an airport hangar–like space, Gavin becomes overwhelmed by all the poor taste on display: the punters in latex or cages; a man with a cattle prod; and another “in a horse’s head,” who “cantered down the aisle toward them, his weirdly long and thin flaccid penis swinging around like a prop.” Everyone there is vying for attention, it seems to him, which is probably why “to the hip collectors and creators he knew, this kind of Utilikilt kink would have registered as sad and profoundly unhip.”

Mountford’s story isn’t a call for galleries to take kink seriously, nor is it a satire on normative tastes but a study in the aesthetics of BDSM and its conflicts with other aesthetic realms. There’s plenty in common, of course, between the spaces kinksters use for exhibitionism and literal exhibition spaces.

The idea of good taste’s vulnerability to desire recurs in Brandon Taylor’s standout story, “Oh, Youth,” about a tall and handsome young man named Grisha welcomed, for a summer, into the marriage of some well-dressed and very rich people. In Taylor’s poised and Jamesian style, Grisha frequently exits his (paying) hosts’ chic parties to smoke cigarettes and stare at the surroundings.

Looking out over the lawn, he sees beyond the chairs the “dark metal of the low fence rimming the perimeter which Grisha assumed had something to do with the hosts’ small silver dog and coyotes.” The inadequacy of the fence’s ability to protect anything or anybody makes Grisha want to laugh, “like it was a pun or a joke out of rhythm.” He is technically an intruder, although an invited one, and the puny little fence reads like a symbol for the way his graying lovers try to use money to control the uncontrollable, like the boundaries of their marriage—a bid for mastery that leaves the best among us looking like fools.

Carmen Maria Machado’s story, “The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror,” presents the most direct challenge in Kink to the conventions of the literary. A sapphic tale set in the theaters of early-twentieth-century Paris, and plenty of fun, the story leans into the silliness of erotica’s vocabulary. Its protagonist uses the rather camp euphemism “her sex,” for example, to refer to her lover’s genitals, and tends toward tragically beating her fists against doors. Such uses of the noun “sex” always remind me of Lady Macbeth’s melodramatic appeal to the gods to “unsex me here, / And fill me from the crown to the toe top-full / Of direst cruelty!”

Such is the occasional corniness of Kink, which is not a literary problem so much as a feature of almost all writing about sex. That’s partly because satisfying real-life sex requires that we get vulnerable and un-self-consciously sincere about our needs, which is a way of communicating quite foreign to the cool and intelligent distance of the professional observer (the curator, the novelist, the critic). Making things worse, we prize originality in our language arts, while sex has remained much the same across the centuries, making cliché almost an inevitability in any sex scene committed to paper.

This must be part of the reason why the terminology of kink dates so fast. In her story “Emotional Technologies,” for example, first published in 2004, Chris Kraus uses the term “SM” for activities like “kneeling on the floor of the downstairs studio awaiting the arrival of a man I met over the telephone named Jeigh.” SM was a term in more common currency in the 1990s and remains emblematic of that decade’s blossoming of the sexual weird, particularly in California’s Bay Area (see: Pat Califia’s Macho Sluts, 1988).

But the term SM is a little out of date, supplanted now by BDSM. It’s just a matter of historical distance, but it’s also a reminder that all versions of this term—BDSM, S&M, S/M, SM—are abbreviations of sadomasochism, itself a word built purely out of literary reference and psychoanalysis. In his 1886 opus Psychopathia Sexualis, Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing made the literary works of the Marquis de Sade and Leopold von Sacher Masoch into the ultimate reference point for “deviant” sex, which then stuck permanently. As with his contemporary Sigmund Freud, Krafft-Ebing pulled a neat trick when he turned bits of complicated fiction into medical terminology.

There are few stronger influences on the way we talk about sex or literature than psychoanalysis, but its own definitions for sexual relations turn out to be yet more chunks of literature. The tendency of erotic writing toward the cliché or corny derives, it seems, from the revolving door of literary reference at the heart of even the most apparently scientific of studies in sexuality. Trying to find the meaning of the word “kink” seems to leave us stuck in it, surrounded by fictions old and new, and as far as we were at the start from the real flesh and blood of what is, after all, a very tangible practice.

Not every story in Kink is a happy one, nor is every one particularly erotic. But each is a portrait of the way sex can turn slippages and differentials in human society—between people trying to understand one another through language, between the strata of power hierarchies, between differing gender expressions—into a phenomenon only fiction can really get at. Kwon and Greenwell’s Kink is an excuse to dwell in this confusion of ideas and juicy social problems, and an invitation to enjoy the sheer inexplicable fact that the body speaks a language we can’t understand.