Although Donald Trump’s status as a bestower of brilliant nicknames was always overrated, the GOP is clearly lost without his marketing savvy. On Friday, House GOP Whip Steve Scalise released a statement lambasting the $1.9 trillion stimulus package that’s expected to be brought to the floor next week as the “Pelosi’s Payoff to Progressives Act.” It is a mouthful—not well suited to hashtags or bumper stickers.

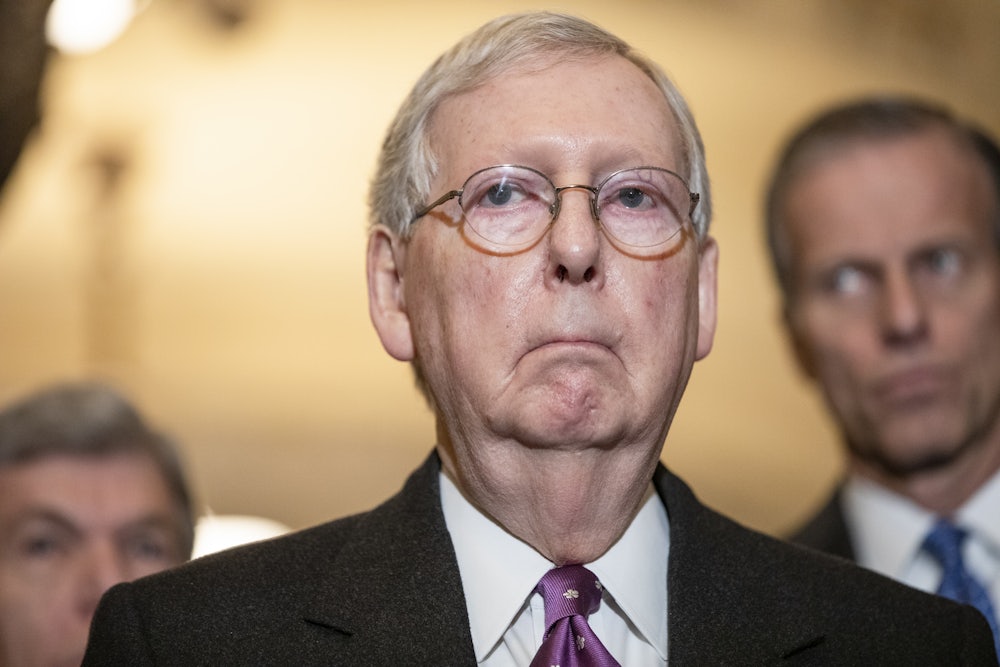

The long-overdue Covid-19 relief bill, Scalise nevertheless argues, is a veritable Christmas tree for Democrats and the socialist hellholes they represent. “This package will keep schools closed, bail out blue states, pay people not to work, and raise the minimum wage to $15/hour,” the statement reads. It also makes food stamps more widely available, offers postal workers more time off, and provides benefits for which some undocumented immigrants might be eligible. You know, bad stuff. On Friday, Mitch McConnell also circulated a memo indicating he planned on challenging the Democrats’ use of budget reconciliation to pass the stimulus, targeting the minimum wage increase in particular.

Republican alternatives to the measure coming to the floor are not to be found, nor have any potential compromises been raised to accompany these sudden objections. Not that it matters, but one is left with the strong impression that the House GOP would oppose this bill even if it included a plethora of sweeteners aimed at winning Republican support.

That, of course, may be the point. Twelve years ago, Barack Obama entered the White House amid somewhat similar circumstances: The economy was in a tailspin; stimulus and relief were desperately needed. His administration spent weeks watering down a bill that was more aimed at winning Republican support than adequately filling the yawning hole in the economy: The bill’s bottom-line figure was kept below $1 trillion so as not to spook the deficit hawks, and much of the relief it did include was engineered to flow into the gap with such subtlety that it was destined to be barely felt at all.

For all of Obama’s entreaties to his political opponents, Republicans rejected it anyway. They were rewarded for all that intransigence first with a big opinion swing against the stimulus and then by a wave election that took back control of the House of Representatives in 2010.

Despite all that has happened between January 2009 and February 2021, Republicans are running the same plays: fighting against economic relief in the hopes that they can use the immiseration that would follow for their political benefit. The bill, if passed, will be lambasted for adding to deficits and benefiting the undeserving. The bill, if spiked, will lead to an insufficient recovery that proves President Joe Biden and his fellow Democrats are failed leaders. There are enormous and worthwhile debates to be had between the two parties after America is lifted out of the crisis: enemies to slay and political points to be won. Republicans would rather order the Code Red, torpedo the economy further in the hopes that the electorate will come to believe that the only solution is to elect Republicans to Congress in 2022. (At which point they will gum up the works some more.)

But this is not 2009. The situation may be vaguely similar—an economic crash following catastrophic Republican governance—but the world has changed a great deal. The Black-Eyed Peas have faded toward irrelevance; most people now acknowledge that The Curious Case of Benjamin Button was bad. And the attacks on Democratic spending have lost some of their spicy tang after another deficit-busting GOP administration.

The Biden administration seems to have learned an important lesson from the Obama era: Republicans aren’t serious about voting for legislation sponsored by Democrats, so there’s nothing to be gained by watering down the big fixes in the quixotic hope of winning their votes. Going big and alone has more political merit than going small and bipartisan. Democrats are wising up to the trick that McConnell pulled in 2009. It’s just not worth negotiating with people who have shown, time and again, a refusal to engage in good faith.

The Republican grassroots has also changed a great deal. Twelve years ago on Friday, Rick Santelli embarked on the rant that launched the Tea Party from the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. That speech was all about how America’s winners—represented by Santelli and his buddies on the trading floor—shouldn’t have to bail out the losers, in this case all of those schmucks who were getting their homes repossessed. These people, Santelli argued, deserved to lose everything because they were foolish enough to be deceived by predatory lenders. For years, the GOP and the Tea Party obsessed over the concept of “winners” and “losers,” the animating idea being that the government should never help people who don’t really deserve it.

It’s a much harder task to sort the “winners” and “losers” of a global pandemic. While it was possible to chide those who took out loans with too-good-to-be-true terms back during the build-up to the subprime mortgage collapse, it’s more difficult to label people “undeserving” in the wake of the coronavirus crisis. The fact that enormous amounts of bailout money have been shoveled in any number of directions over the past 11 years, right down to Trump’s stock-buyback-bingeing tax cuts, still looms in the memories of Americans who feel that they’re entitled to some consideration for having to struggle in the teeth of a global health crisis. The idea that the poor are, by their very nature, morally unfit and thus excludable from government aid, still persists on the American right, but these critiques don’t seem to pack the same punch that they did a decade ago—at least not where the pandemic is concerned. Republicans had held on to a thin slip of small-government credibility, despite several consecutive GOP administrations that enlarged the deficit. That credibility is all gone now.

And the Santellian rhetoric that paved the way for the Tea Party no longer seems to be the argument of first resort for the grassroots right or the media elites whose product they consume. The issues that animate conservatives almost all revolve around culture-war battles, and Republicans don’t seem to want a shrinking government as much as they want to pass laws that banish Democrats from it. Ranting about the deficit just doesn’t quicken the blood the way it once did after four years of Trump. There are much more exciting and insane ideas to thrill to now, such as a stolen election and a cabal of blood-drinking Democrats who secretly rule the world. In this context, the difference between a $1.9 trillion stimulus and a $700 billion stimulus barely rates. How could it?

The media also seems to have learned some lessons from the radicalization of the GOP. Once, a lack of opposition votes was a scandal in miniature. In 2009, McConnell was able to weaponize that idea, pushing the Obama administration to downgrade its asks without ever having to give anything up in return. McConnell got cover from media luminaries such as David Broder, who approvingly cited Obama’s bipartisan yearnings: “The president has told visitors that he would rather have 70 votes in the Senate for a bill that gives him 85 percent of what he wants rather than a 100 percent satisfactory bill that passes 52 to 48.” It’s taken a while—and a deadly pandemic—but many in the often fabulously naïve Beltway press have gotten smarter. Now the narrative is increasingly centered on McConnell’s intransigence, rather than some failure on the part of Democrats to persuade Republicans to vote for legislation that would have been bipartisan not that long ago.