Less than a decade ago, it wouldn’t have taken much to imagine either Andrew Cuomo or Rahm Emanuel in the Oval Office as president about now. Cuomo, elected New York governor in 2010, and Emanuel, who became Chicago mayor in 2011, had always radiated a lean and hungry look. Their raging ambitions and their tough-guy personas suggested that they could get big things done—no matter how many aides and politicians they threatened and broke in the process.

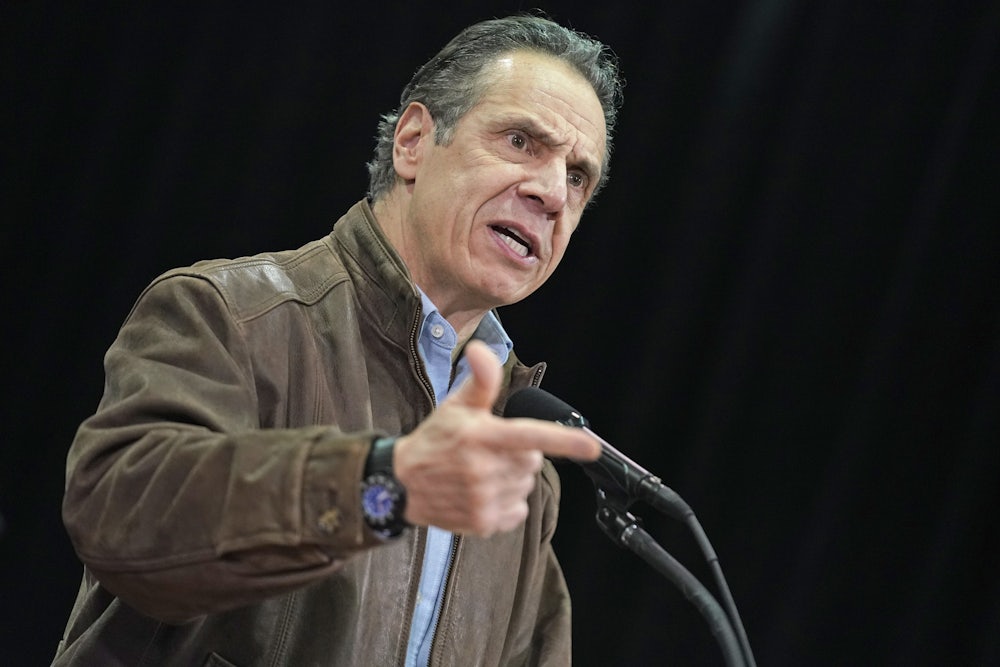

Emanuel unexpectedly bowed out of a third-term race for mayor in 2018, partly because of the festering controversy over his efforts to keep secret the details of the 2014 police killing of Laquan McDonald, a Black teenager who was shot 16 times while carrying a small folding knife. And now Cuomo, weakened by his cover-up of Covid-19 deaths in nursing homes, is desperately clinging to his job as he confronts three credible, on-the-record accusations of sexual harassment: In a press conference on Wednesday afternoon, he insisted that he “never touched anyone inappropriately” and refused to resign.

The eclipse of Cuomo and, to a lesser extent, Emanuel signals the welcome end of the cult of barroom brawlers in the Democratic Party. This archetype dates back to the Kennedy years—with the ruthless Bobby Kennedy as attorney general, followed by the intimidating Lyndon Johnson as president. During the 1960s, the Democrats felt they had to prove that they were men of action willing to take on the Soviet Union and demonstrate that they could fight communism in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

This tough-guy approach to politics returned to Democratic vogue during Bill Clinton’s presidency, in which both Cuomo and Emanuel played key roles. Stung by the Democrats’ three straight landslide defeats for the presidency in the 1980s, Clinton ran for the White House convinced that the Democrats had to refute Ronald Reagan’s claims that they were soft on crime and coddlers of welfare recipients.

Cuomo and Emanuel are the embodiments of this bully-boy style. Many Democratic insiders—and a significant chunk of political reporters—believed that this was the way to lead in difficult times, especially with the Republican right on the march. But in truth, the twenty-first-century Democrats who tried to govern solely through fear did lasting damage to the party with their emphasis on intimidation rather than idealism.

Cuomo and Emanuel both entered politics armed with gold-plated brass knuckles and a zest for using them. Andrew Cuomo terrorized Albany in the 1980s as the enforcer for his cerebral father, Mario, who spent three terms as New York governor. Emanuel, already famous for sending a dead fish to a pollster, spent election night 1992 brandishing a dinner knife as he loudly proclaimed future White House vengeance on Clinton’s Democratic enemies.

They both also hungered for far more than a backstage role as a backstabber. Cuomo spent the Clinton years at the Department of Housing and Urban Development and was elevated to the Cabinet for the president’s second term. Meanwhile, he plotted a triumphant return to New York politics. Emanuel, after a lucrative stint as an investment banker, was elected to the House in 2002 and then gave up his Democratic leadership post to become Barack Obama’s first White House chief of staff.

When Cuomo ran for New York governor in 2010, after a stint as state attorney general, reporters often framed his tough-guy reputation as part of the package. A New York Times Magazine profile by Jonathan Mahler described him as “ruthless” and shrewdly noted, “If Mario Cuomo’s Achilles’ heel had always been his ambivalent relationship with his ambition, Andrew Cuomo’s was his unambivalent relationship with his.”

After leaving the Obama White House to jump into the Chicago mayoral race, Emanuel ran a high-priced ad campaign designed to paper over his rough edges. But as Chicago Tribune columnist John Kass wrote, “This new Sympathetic Rahm might make some of us forget about the old Ruthless Rahm, the same guy who ran for Congress with the help of an army of knuckle draggers sent from Mayor Richard Daley’s City Hall.”

Ruthless was once the favored adjective to describe Bobby Kennedy as attorney general in his brother’s Cabinet. A former aide to Joseph McCarthy (really), Bobby Kennedy in 1963 gave his approval for the FBI to wiretap Martin Luther King. The eavesdropping was kept secret until 1968, but Bobby’s take-no-prisoners style as attorney general reflected the hard-boiled realism that was a major selling point of JFK’s presidency. No longer would Democrats be perceived as marshmallow men unwilling to go eyeball-to-eyeball with the Soviet Union like Adlai Stevenson and Hubert Humphrey, both of whom Kennedy beat for the 1960 nomination.

Lyndon Johnson later embraced many of the same tactics. His crude humiliation of loyal aides makes Andrew Cuomo’s berating of Albany insiders seem like a chapter from Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. Both when he was Senate majority leader and president, LBJ was known for the Johnson Treatment, a persuasive technique that was part threat, part relentless argument, and part promises of favors like campaign contributions from Texas oilmen.

Both Emanuel and Cuomo grew up hearing the echoes of the Kennedy and Johnson years and may have unconsciously aped their approach to politics. But thuggish behavior was not Johnson’s true political strength. Johnson was able to pass the landmark legislation of his presidency—the civil rights bills, the creation of Medicare, and the War on Poverty—not only because of his bullying but, mostly, because of a burst of national unity following the Kennedy assassination and the lopsided Democratic congressional margins flowing from the landslide defeat of GOP nominee Barry Goldwater in 1964.

Cuomo never quite learned that lesson. Even though he reveled in his cult following from his Covid briefings, the New York governor always appeared to believe that fear was a stronger emotion in politics than love. And the press, especially during the Covid crisis, bought the myth of Andrew the Terrible, believing that his terrorizing tactics were what had made him such an effective leader in a pandemic. Despite the chilling death toll in nursing homes in the state, Cuomo was widely hailed as the man for the moment. As Vanity Fair put it in a largely fawning profile in the magazine’s June issue, “Many of the traits that Cuomo’s New York political antagonists disdain—his micromanagement, his tactical scheming, his need for control—are proving to be his strengths in this crisis.”

In truth, there was nothing exceptional about Cuomo’s leadership in the crisis, beyond the schoolyard antics that accompanied his feud with Bill de Blasio, New York City’s easily mocked mayor. Yes, New York faces unusual pressures as America’s gateway to the world, since every international flight that arrives at JFK Airport runs the risk of accelerating the pandemic. That could have explained why infection rates in New York spiked so quickly last spring. But it doesn’t explain why the state has a humdrum record on vaccination. According to data compiled by The New York Times, New York is slightly below average in providing both first and second shots. The state, in fact, is roughly on par with Florida—and no liberal has ever put its Republican Governor Ron DeSantis on a pedestal.

In a sense, Emanuel may have the last laugh. Even though opposition from left-wing Democrats scuttled any hope that the former Chicago mayor would be given a post in Biden’s Cabinet, Emanuel is still jockeying for a plum ambassadorship to a country such as China or Japan. Meanwhile, Cuomo is looking like he will be lucky to last out his gubernatorial term.

Growing up in Queens in the 1970s, Cuomo was undoubtedly exposed to an inescapable ad campaign in which Frank Perdue bragged, “It takes a tough man to make a tender chicken.” Of course, the details of modern chicken processing are not for the squeamish. During his decade as governor, New Yorkers with delicate sensibilities have also averted their eyes from the details of how Cuomo has dominated Albany. But these days—as Cuomo is learning all too well—the chickens are coming home to roost.