Melekh Bibi—King Bibi—has been dethroned. Usurped by his former deputy, Naftali Bennett, in early June, Netanyahu was finally dealt an election result with which he could not form a majority government. For the time being, as of June 13, a tenuous coalition of parties across the political spectrum, led by a longtime face of the West Bank settler movement, now has control.

You can’t argue with a straight face that anything is “different” than it was before. Much like Trump, Netanyahu was much less of a departure from his nation’s “democratic” “norms” than political and media elites would care to admit. Bennett’s arrival was heralded by a fresh wave of provocations in East Jerusalem and deadly bombings in Gaza. Neither Biden nor Congress appears interested in increasing pressure on the Israelis to ease up. Bennett has reportedly assured his colleagues that there will be no halt to settlement construction on Palestinian land under his watch.

All of which is to say that Benjamin Netanyahu’s exit, far from auguring some sort of new political era, heralds only horrible continuity. That he has succeeded is indisputable: He is the longest-serving Israeli prime minister, and Bennett will largely be sticking to a script that Netanyahu wrote. But what accounts for the success of his reign? There is the Joe Friday answer: a combination of P.R. savvy, the good fortune to have a war hero as an older brother, and the foresight to have spent years cultivating wealthy allies around the world before many of his domestic rivals.

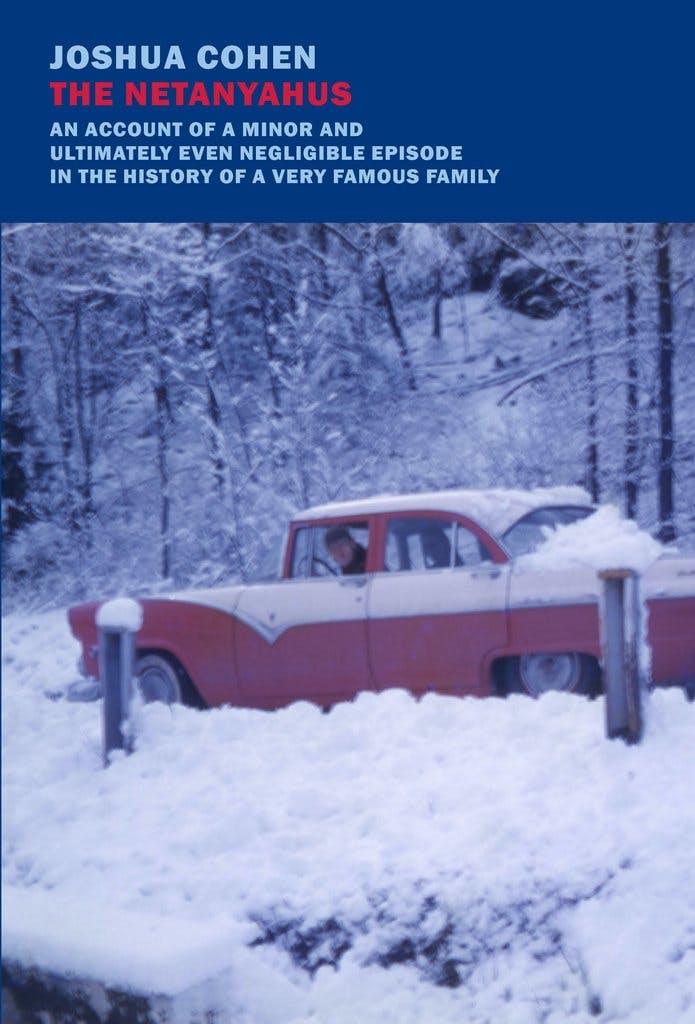

And then there is Joshua Cohen’s answer. His latest novel, The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, provides something of an origin story for a political family that has sought nothing less than to make itself into an emblem for all of Israel. In The Netanyahus, Cohen has found a semifictional historical tapestry adequate to his vast imagination. He has written one of the only genuinely funny novels of political satire to be published since Donald Trump was elected president. Best of all, by invoking archetypes of claustrophobia—the liberal arts college, sexual rebellion, in-laws, stale dinners, creaking boards, cramped reading spaces, sneezes, twitches, farts—Cohen is working in new territory for the Netanyahus, successfully cutting the dynasty down to size while bringing its delusions of grandeur into relief.

The narrator and shadow protagonist of The Netanyahus is Ruben Blum, a retired Jewish professor of American history at fictional Corbin University. His tale concerns the January 1960 campus visit of the Jewish historian of Jewish history Benzion Netanyahu, the all-too-real father of Benjamin. Being the sole Jew on the faculty, Blum is tasked by his department chair with supervising Netanyahu’s visit, a distinctly midcentury kind of anti-Jewish bigotry that leads Blum to open the novel by insisting to the reader that although he is a Jew and a historian, he is not a historian of Jews. This distinction is important. Blum views himself as a keeper of the American faith both in personal conduct and professional practice: Swede Levov meets Skip Gates.

Blum’s home life is so-so (“The truth was this: my wife was bored and my daughter was angry”). After uprooting his family from the exciting city to the goyish countryside, believing not without reason that he had finally made it as an academic, Blum’s primary sources of discontent come from the home front. The parents of his wife, Edith, are elitist German Jews, while Blum’s own background is that of poverty and piety and points of origin further East. His teenage daughter, Judith, hates the world, her large nose most of all. The campus novel may be an unexpected métier for Cohen. The genre’s opportunities for wordy dialogue and ironic melodrama clearly favor him, and the 800-pound gorilla of Zionist ideology does not have to be explicated through the clipped grunts, as in his previous novel, Moving Kings, of freshly graduated Israel Defense Forces alumni.

Although the Netanyahus are from Israel, by the novel’s opening in 1959, as in real-life, Benzion, his wife, and their three sons are settled in Philadelphia. Benzion is a professor at Dropsie College, a now-defunct graduate institution of Jewish studies, desperately in search of more prestigious and remunerative work in American academia. In the months preceding the Netanyahus’ family visit, Blum hides himself in his attic office, sifting through Benzion’s corpus: letters of valediction and scorn, the historian’s C.V., and his bizarre scholarship on Jews under Spanish rule in Medieval times. Blum suffers through the visits of his in-laws, whose differing conceptions of success, family, and Jewishness will come to feel like kisses on the cheek compared to the bitch-slap of the “Yahus,” as he takes to calling them in his head.

Benzion Netanyahu was not a larger-than-life figure and, according to Cohen, the basis for this novel came from a tossed-off story told by Harold Bloom, who had once hosted Professor Netanyahu for a campus visit. But proximity breeds intrigue. Although father and son mostly downplayed their link, Benzion’s Manichaean sense of Jews and the world has long been suspected to have rubbed off on his middle son, the former Israeli leader. And though the since-deceased Benzion would probably dispute it, the historian would best be described as a faithful adherent to what another Jewish historian, Salo Baron, identified as the “lachrymose” school of Jewish history. That is, those who view Jewish history as a string of tragedies stretching from the destruction of the Second Temple to the Holocaust. “Jewish history is in large measure a history of holocausts,” Benzion infamously told David Remnick in 1998. “Carried out by anti-Semitic leaders and factions that managed to take over whole countries or regions in times of anarchy, civil war, or rebellion. In the areas that fell under their control, all Jewish communities were wiped out.”

In Benzion’s view, this unbroken cycle of tragedy was only marginally eased by the founding of Israel in 1948, but a muscular Zionism to repel the outside world remained the only strategy for survival. The specific Jewish tragedy with which Benzion was obsessed was the Spanish Inquisition, the competitive fifteenth-century-and-onward efforts between the pope and the Iberian kingdoms to root out supposed “crypto Jews.”

Benzion Netanyahu, as Blum deadpans it, essentially subscribed to an elaborate conspiracy theory about the true nature of the Inquisition:

The true purpose of these inquisitions wasn’t doctrinal; they weren’t supposed to investigate heresies or convert the Jews or ensure that the Jews who converted remained faithful Catholics—not at all. Instead, their true purpose—never publicly stated, but privately acknowledged—was to invalidate new conversions and turn as many new Christians back into Jews as possible.

This is what Benzion Netanyahu actually believed—that everything that is known about the Spanish Inquisition is a lie, the biggest lie of all being that its purpose was to Catholicize the so-called conversos and marranos. In his interpretation, the Inquisition was not about the supremacy of Christianity but entrenching Jews as an object of goyish hatred. His life’s work was devoted to proving that not only were the Jews a nation, they were a nation whose innate goodness of character naturally made them a perpetual scapegoat. The Spanish Inquisition, ostensibly to stamp out Judaism, was another clandestine effort to secure the Jews’ fixed subaltern position by keeping them as Jews.

“I confess I felt ashamed about it, this secret study of mine, this sudden hidden lucubration, my unexpected resurgence of interest in subjects Jewish,” Blum writes of his evenings obsessively reading Netanyahu’s materials prior to the visit. Blum’s shame does not come from a buried sympathy springing forth; it is due to the “bewildering” fact that Benzion is a “believer.” Meaning, “if there was any distinction at all between what he believed and what the rabbis did, it was that Dr. Netanyahu preferred to attribute the power of change not to a deity acting in accordance with an inscrutable design but to the world’s vast stock of gentiles who acted out of hatred.”

In glimpses of Netanyahu family life that come into view two-thirds of the way through the book, Cohen shows that the best literary twists on political characters rest on inventing entirely new worlds for their readers, allowing them to see familiar brokers of the established order in entirely unfamiliar contexts. A scene from a few minutes after Benzion, his wife, Tzila, and their sons, Yonatan, Benjamin, and Iddo, arrive at the Blum family home in Corbindale:

But Benjamin was leaning over his younger brother’s ashy nakedness and flicking at his penis. Tzila slapped his hand away and Iddo howled. “Chocolate chip poop cookies,” Benjamin said, pointing into the diaper, “chocolate chip brownie fudge poop cookies.”

At the time of this story Benjamin is 10 years old, and his

younger brother, Iddo, is seven years old. The diaper is due to youthful

incontinence; Cohen imagines Netanyahus who could not abide pit

stops for their kid, one of many colorful

pieces of evidence the novel conjures to illustrate how Benzion’s monomania

ripples outward through the family in weird ways. Attending her husband’s guest

lecture at the college, Tzila borrows Edith Blum’s jewelry without requesting

permission. “Edith held Netanyahu’s coat out for him and he awkwardly armed

into it: he was unaccustomed to the help.” Their babysitter had canceled,

requiring them to bring the kids, because of “a flood from pipes that are

freezed and a fire.” When Benzion picks up a photograph on a table, he replaces

it upside-down. Predictably, the manic right-wing Zionist has a bizarre formal

interview with the faculty before he is to deliver a guest lecture on the

subject of his work, the Jews and the Spanish Inquisition. Without the might of

an occupying army, the protection of the lectern at the U.N., or the false

transparency of the television camera lens—and stuck in the living room of a

mild-mannered liberal academic—the “Yahus” make an undignified spectacle.

Benzion Netanyahu’s guest lecture, which precedes the climactic ending of the novel, provides the only moment at which Cohen lets a little bit of his sympathy for Benzion show, as expressed by Blum. “The Spanish Inquisition became the first institution in world history to treat Judaism primarily as a race, as a sanguinary quantum and heritable trait that could not be lost or abrogated,” Netanyahu thunders from the lectern to an uninterested audience, listing Jewish suffering at the hands of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and the expulsion of Jews from the Arab umma as examples. Blum says that while at the time he thought Benzion sounded harsh, upon recollection, “I find it poignant.”

Poignant though Blum/Cohen may find Benzion’s digest of twentieth-century Jewish catastrophe, The Netanyahus gives Benzion’s scholarship more than its historical due. The elder Netanyahu was a prolific crank, a close reader of ancient languages whose scholarship was roundly criticized by most of his contemporaries. In 1967, a few years after the events of The Netanyahus, Benzion did receive a comprehensive review from a contemporary historian of the Jews, unlike the Jewish historian Ruben Blum. Gerson D. Cohen, future chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, concluded that The Marranos of Spain: From the Late XIVth to the Early XVIth Century According to Contemporary Hebrew Sources, while certainly the work of an active mind, amounted to scholastic bupkes. According to that review, Netanyahu based his study on “one set of sources alone where there are others available,” functionally an accusation of cherry picking his sources.

“Professor Netanyahu may choose to disqualify the whole mass of Inquisitorial evidence utilized by … earlier students in that field as one pack of lies,” Gerson Cohen wrote. “If so, then his discussion should have been integrated with an evaluation of seemingly contradictory materials, or he should have postponed all weighing of the evidence until after having presented the other side of the case. As matters stand, Netanyahu’s study, at best, leaves us in mid-air.” At the time of Benzion’s death in 2012, the Jewish intellectual historian David N. Myers affirmed what Gerson Cohen had written 45 years earlier, noting that the heretic historian “was frequently criticized for ignoring the veracity of the largest trove of documentary material relating to the conversos.”

Netanyahu’s scholarship was out of step with that of his peers, not just in technique but in its thrust. In his 1982 masterwork, Zakhor, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, a Jewish historian at Columbia University, identified an interminable contradiction at the heart of writing Jewish history in the modern era: Scholars had to tell the story of “the belief that divine providence is not only an ultimate but an active causal factor in Jewish history, and the related belief in the uniqueness of Jewish history itself,” without actually enacting those beliefs themselves. Whereas scholars like Yerushalmi were grappling with these difficulties, Netanyahu had no use for them—seeing a fixed place for Jews in time and space across hundreds of years, aligning messianic visions of Jewish nationalism with Jewish religion.

In a recent interview, Cohen has noted that “there’s a whole lot of Zakhor-parody in The Netanyahus,” that is expressed as “me channeling Benzion Netanyahu’s mockery of Zakhor.” This mockery is not explicit but expressed more broadly in Benzion’s disbelief that a Jew would look at the Gentile world and see anything but hostility. (Toward the book’s close, Benzion argues with Blum not merely over prompt payment of his honorarium but over whether his prospective employer would pay it at all). Because while Yerushalmi would have denied the specific historical claims of Netanyahu regarding the conversos, he like Netanyahu identified that a “racialized” sorting of Jews took place during both the Inquisition and in Nazi Germany. As Cohen notes in the interview, “from a Revisionist point of view, Yerushalmi was a poet, or was poetic, but blanched before the political implications of his thesis.” Benzion sees himself as one of the few who does not blanch.

If we were to characterize Benzion Netanyahu’s theory of the Inquisition as a school of thought, it would be, Myers argues, an “Amalekite view of Jewish history.” “Zakhor!” the Old Testament intones, urging Jews to remember the tragedies dealt to them by the nation of Amalek. In the book of Samuel, King Saul is commanded by God to destroy Amalek for attacking the Israelites during their exodus from Egypt. In the so-called “Amalekite view,” the memory of victimhood necessitates the destruction of the enemy. In enlightened times, the word for this is now “defense.”

The biblical imperative against Amalek is a good match for what Myers calls the elder Netanyahu’s “own militant Zionism, which demanded a persistent willingness to wage war against one’s enemies.” There is no statement about Benzion in this paragraph that would not also apply to most Israeli politicians today, including his son, who has repeatedly invoked the name “Amalek” to describe variously Iran, Palestine, and other enemies. Though Benzion was an obscure scholar who spent much of his adult life outside Israel, his perspective has explanatory power for reasons unrelated to the prominence of his children.

Cohen is fortunate to have the best of all endings, which is simply history as it happened. Jewish catastrophes, at least of the variety that produce body counts at the level of genocide, ceased to happen to Jews. Israel got a nuke, and with the help of just about every other Western power, Israel has striven to be a state that does bad things to other people and not a state to which bad things happen.

Benzion Netanyahu went on from Dropsie College to the University of Denver and later a tenured position at Cornell, and he died in 2012 at the age of 102. Among American Jewish academics, he remained a bizarre loner, and most of the people he would have considered his contemporaries in Israel had been dead for years. All three of Benzion’s children served in the Israeli Special Forces; Yonatan died in the raid on Entebbe, becoming a martyr through the skillful manipulation of his image by Israel, Hollywood, and his family. Iddo is a doctor and a playwright, and he splits time between Israel and New York. And Benjamin?