Nearly every hospital in the United States appears to be flouting Trump-era rules mandating price transparency, according to a bombshell new study. Put into effect on January 1 under the Trump administration, the new directive requires hospitals to make rates they negotiate with different insurers for procedures publicly available—a move proponents argue curbs runaway health care costs by stripping hospitals of the market-hobbling opacity that’s long benefited their bottom lines. The new research published by the nonprofit group Patient Rights Advocate determined that 471 of 500 hospitals examined were not in compliance with the new rule, results even more shocking than a previous study in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimating a mere 80 percent of hospitals to be in violation. The Biden administration recently directed the Department of Health and Human Services to enforce the rule as part of his extensive executive order aimed toward facilitating market competition.

It’s worth emphasizing just how conservative this line of thinking is: Not only does the fetishization of price transparency endorse the idea of health care as a market good, it also embraces a vision of patients as consumers, saddled with the arduous task of dutiful comparison shopping whenever they require care. Never mind that the path to universal health care in practically every country that has it relies heavily on public sector financing and coordination, instead of an optimized marketplace.

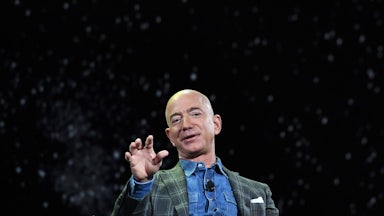

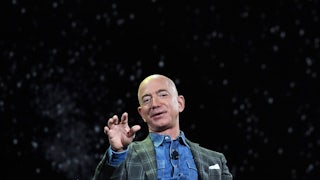

The price transparency policy was largely pushed by Cynthia Fisher, a Republican donor who convinced Donald Trump to enact the rule. Her goal is not just to reduce prices but to stand as a bulwark against more far-reaching change. In an interview last year with Morning Consult, she said, “This is a shape-shifting moment—we’re at this inflection point.… It is probably the last moment of time for transparency, or we go to Medicare for All.” But Medicare for All, not a piecemeal market-based approach, is the only way significantly to reduce America’s uniquely high medical bills.

Though insurers are often the most villainized part of the system, hospitals shoulder plenty of blame for our health care catastrophe. Hospitals gobble up almost a third of our national health care spending, topping $1 trillion annually. The American Hospital Association is one of the most formidable trade groups on Capitol Hill and has been a fierce opponent of not only single-payer but the public option and other watered-down reforms, as well. In most cases, it’s safe to say that hospitals have the upper hand over insurers when it comes to reimbursement negotiations, particularly when they consolidate or otherwise dominate a given geographical area.

The sums that hospitals are able to extract from payers have been widely lambasted as both astronomical and irrational, differing by tens of thousands within the same hospital or for the same procedure, depending on a patient’s insurance plan. In extreme cases, hospitals have come after their own patients with lawsuits to recoup medical debt, roping them into ruinous repayment plans for years after their treatments. In short, hospitals are so unsympathetic that critics frequently chide left-of-center health care commentators for going easy on them compared to insurers, implicitly echoing the conclusions invoked by the title of the legendary 2003 paper by health economist Uwe Reinhardt that health care costs are largely driven by hospitals’ eye-popping reimbursement rates: “It’s the prices, stupid.”

But what if the problem is the existence of “prices” at all? Why do we talk about the “price” of an appendectomy and a blood transfusion but not about the “price” of one 40-minute math lesson for a fifth grader and a half-hour of detention after school? In the U.S. health care system, the “price” of a given service is the amount a given facility gets reimbursed for it by the patient’s payer—amounts that differ wildly depending on a variety of factors. As historian Gabe Winant chronicled in his book The Next Shift: the Fall of Industry and the Rise of Healthcare in Rust Belt America, the 1980s switch from calculating reimbursement by length of patients’ stay to the “price” of care received only served to spur the corporatization of hospitals by rewarding capital-intensive high-tech and invasive care over the services offered in simpler community hospitals—empowering the bigwigs to bill for more high-cost procedures and snap up the smaller players that couldn’t. This gave large hospital chains even more market power to break the backs of whatever insurer tries to argue with them.

But the problem with that dynamic isn’t “prices,” it’s power—a problem that price transparency does little to solve. To borrow Winant’s example, it’s tough to imagine Pittsburgh insurers holding onto too many customers were they to decide not to include University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in their networks, suggesting that listing negotiated prices could only apply so much downward pressure through competition. But even in a perfect world, transparency still wouldn’t offer much in the way of patient relief: Most hospital visits entail thousands of dollars’ worth of care even when coherently priced, so a slight reduction would leave most patients with roughly similar out-of-pocket expenses, even if their insurers save a bit on so-called “medical loss.” Framing that as a boon for health care “consumers”—a ghastly phrase the proponents of this scheme sure do seem to love!— is disingenuous at best.

Medicare for All, on the other hand, wouldn’t just obliterate health insurance as we know it, it would upend hospitals’ ability to bilk payers and patients in the process. With private insurers barred from selling plans that duplicate the benefits of the single public pool, and with providers barred from taking cash for procedures covered by Medicare, hospitals lose the privileged position they enjoy over a fractured field of insurers whose existence—unlike hospitals—provides us exactly nothing of value. The vision outlined in Representative Pramila Jayapal’s House bill essentially transcends the concept of “prices” at all, allocating each hospital a global operating budget akin to a fire department or school. Medicare for All would also impart strict control over profits and capital expansion: Hospitals wouldn’t be permitted to keep or reinvest surplus revenue, or beef up facilities without public approval, rendering it all but impossible for them to keep taking cues from corporate playbooks.

As we move toward the more just hospitals of the future, we deserve to aim beyond a tedious master list of prices. The Biden administration is struggling to get hospitals to disclose their prices, but this is fighting the battle the wrong way around. Instead, it should be looking for a way to kneecap the power of hospitals to set them in the first place. Scrapping private insurance is the best way to do it.