Navigating the meat aisle is getting more complicated. Plant-based meat alternatives had $1.4 billion in sales in 2020, growing 45 percent year on year. Faux-meat burgers, sausage, and nuggets are slowly finding a foothold not just in the home but also on restaurant menus and grocery lists. Meat produced via cellular agriculture is probably next: Widely hyped in some circles as a potential solution to humanity’s unsustainable addiction to meat, this technology has been the subject of widespread and often rancorous debate over its scientific and economic viability, its financial links to Silicon Valley venture capital and incumbent meat companies, and the desirability of using taxpayer money to fund its research and development. And no one can agree on what to call it.

As the rise of nontraditional meat accelerates, the Agriculture Department is seeking input on names for these novel foods “that would be neither false nor misleading.” This question is particularly important for cellular agriculture; unlike plant-based meat analogues, meat produced from cells in a growth medium is biological animal tissue, just produced differently from conventional animal meat. And as the case of so-called genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, shows, linguistic missteps as a technology emerges can cause long-term problems with regulatory clarity and public trust.

Meat alternatives have been part of global culinary traditions for centuries. For instance, Chinese and Japanese cooking has long featured mock meats such as seitan and tofu, and tempeh has long been a staple in Indonesia. But these products are clearly not meat. Even the early branded faux-meats, like Quorn and Tofurky, never claimed to be something they’re not, wearing their badge of artful imitation with pride. Newer entrants into the field, however, are both trying to replicate meat and claim the mantle of “meat.” Impossible Foods, for instance, uses soy and synthetic heme to mimic the taste and mouthfeel of beef, and refers to its product as “meat made from plants.” This has raised hackles among both beef producers and some members of the food movement, who have rallied against “fake meat.”

This is an interesting linguistic development, given that the etymology of the word meat can be traced back to the old English mete, which denoted foodstuffs more generally. (It wasn’t until far more recently that meat came to refer almost exclusively to flesh.) But it’s a high-stakes political and commercial issue as makers of “alternative proteins” seek to—in the Silicon Valley vernacular that permeates the nascent field—disrupt the $200 billion-per-year meat industry.

The United States does not have a federal definition of meat because it has never needed one. Until recently, meat was meat. The brash claims of companies like Impossible push against this status quo. But the existence of cellular agriculture, which allows real animal fat and tissue to be grown from base cells, upends the conventional meat industry’s assumed claim to the word. This technology, as an article in the journal Science as Culture puts it, represents an “attempted reorganisation of contemporary food economies and ontologies,” destabilizing “established understandings of what food is.” By altering our taken-for-granted physical reality—making meat without killing animals—novel food technologies disturb our taken-for-granted linguistic and regulatory categories.

Cellular agriculture has moved from pipe dream to proof of concept to commercial sale relatively quickly. The first prototype beefburger was taste-tested in 2013. 2020 saw the first commercial launch of cellular chicken in Singapore. Now cellular agriculture companies are planning limited market launches in the United States. In 2019, the USDA and the Food and Drug Administration agreed to co-regulate the new technology, but they didn’t take a firm position on nomenclature. Nor is there consensus within the industry itself. Early scientific research referred to “in vitro meat.” Until a few years ago, the preferred choice among some advocates was “clean meat,” connoting a parallel with clean energy. Now the Good Food Institute, an alternative-protein nonprofit, argues that “cultivated” is best, presumably because it references the process of growing cells in a culture. New Harvest, a nongovernmental organization dedicated to developing cellular agriculture, uses “cultured” but has no fixed position on the term. The Alliance for Meat, Poultry and Seafood Innovation, a consortium of cellular agriculture start-ups, uses “cell-based/cultured.” Critics, journalists, and even some supportive commentators have tended toward “lab-grown.”

No one has taken these debates more seriously than incumbent meat producers, who have launched legal efforts, often backed by supportive politicians, in a number of states and federally to restrict the use of terms like meat and beef and chicken to the corpses of animals. (Most recently, the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association petitioned the USDA to prevent products of cellular agriculture from being labeled “meat”; its petition was denied.) This matters because alternative protein companies’ success in the market depends on consumer uptake, which could be affected by being unable to call the products meat—or, worse, if they are branded with a prejudicial prefix like “fake” or “imitation.”

The “Frankenfood” criticism is also one that was lobbed at GMOs—another food haunted by labeling debates. A 2014 segment from Jimmy Kimmel’s late-night comedy show followed an interviewer into a farmers market in California, asking shoppers, “What does GMO stand for?” Most of the respondents couldn’t explain the acronym, yet they authoritatively stated that GMOs are bad. The video is entertaining, but it shows that the term GMO itself, separated from any factual meaning, elicits a negative reaction and influences consumers’ purchasing habits.

Unless you’re purchasing a Hawaiian Rainbow papaya, it’s unlikely you’ll find a GMO in the fresh produce section of the grocery store. But GMOs are grown widely in the United States; over 90 percent of American corn, soybeans, and cotton are varieties genetically modified to be insect-resistant or herbicide-tolerant. More than 95 percent of meat and dairy animals in the U.S. are fed GMOs. While there are exceptions, most of these GMOs have been deployed by large multinational corporations focused on large-scale farming operations. But as the effects of climate change increasingly threaten crops, scientists believe these techniques can contribute to the urgent food system transformation required to make agriculture more resilient and feed the world sustainably.

Because humans have been “modifying” crop genetics since the beginning of agricultural societies, many scientists see genetic modification as an extension of conventional plant breeding. But when genetically modified organism entered the vernacular in the 1980s and 1990s, the term was specifically referring to recombinant DNA technologies, also called “transgenic,” in which genetic material from one organism is transferred into the genome of another. Settling on the relatively broad and ominous term genetically modified, rather than recombinant or transgenic, left the door wide open to interpretation.

These two words have ricocheted through the public imagination for decades, conjuring science-fiction images of vegetables pieced together in labs like a botanical Frankenstein’s monster. American skeptics of the technology have long lobbied for official labeling of foods containing GMOs. Government agencies have resisted, citing the conclusions of independent scientific bodies that genetically modified crops pose no more risk to human health or the environment than conventionally bred crops.

Yet the undeniable marketing success of the Non-GMO Project shows how wary Americans are of these products. This organization sets its own definitions of what constitutes a GMO ingredient and charges food companies to mark their products with the Non-GMO Project logo to assuage consumer concerns.

Terminology is as important for regulating a technology as it is for public perception. Unlike in the U.S., the words “genetically modified organism” are actually written into European policy in the EU’s “GMO Directive.” But this nomenclature has recently led to considerable commotion as it was unclear how emerging “gene editing” methods—which, unlike recombinant DNA techniques, can generate precise mutations in a plant’s own genome instead of inserting genetic material from a different organism—would be regulated. The European Court of Justice ruled that gene-edited crops would be regulated as GMOs because of the novelty of the method, even though they can be technically indistinguishable from products that are exempt from such regulation. This has only led to more uproar and questions of whether the directive is actually effective for emerging technology. In one of its first actions post-Brexit, the United Kingdom tossed out the European ruling and announced plans to relax regulation of gene editing in order to help achieve climate and nutrition goals.

Language choices helped set the stage for all this—something those currently adjudicating the language and regulations surrounding cellular agriculture should keep in mind. New innovations will always push and pull against the boundaries of language. It is important to choose terms that fairly, clearly, and precisely represent the new meat-producing technologies, rather than simply giving in to the meat industry’s attempts to restrict nomenclature or rushing into legally enshrining terms now that can cause problems in the future.

The question of what to call new forms of meat can also be an opportunity to ask questions about the sort of world we want to live in. The meaning we attribute to words changes frequently in response to both technological and social changes. The term “car,” for example, as the philosopher Andy Lamey has pointed out, once referred to horse-drawn trams, then almost exclusively to combustion engine vehicles, and now encompasses electric vehicles—the term expanding and shifting as new technologies emerged and others became obsolete. The definition of “car” required revision because early definitions relied on “one particular conception of cars” rather than getting at the central concept. The same should happen “to make room for in vitro meat,” he wrote, accepting meat as anything that “has a meaty substance and function. Just as Model Ts and Teslas both qualify as cars, animal-sourced and lab-grown versions would then both qualify as real meat.”

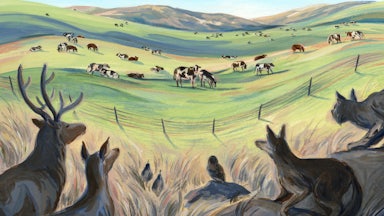

There is a flip side to Lamey’s argument, however, which is equally important. If we accept that the new meats differ from conventional ones only in how they are produced, we can stop to reexamine whether our old way of doing things is actually preferable from an ethical or environmental perspective. Tradition isn’t always best: Solar and wind power are unambiguously better from a planetary perspective than fossil fuels. Agriculture that excludes synthetic fertilizer, genetic modification, and certain agrichemicals is associated with lower crop yield per hectare, which means that traditional “organic” agriculture may have some downsides when it comes to conserving natural habitats and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from converting land to agricultural uses. Should we call it “land-extensive production” instead?

Similarly, the new meats should prompt us to consider the origins of conventional meats. Calling conventional meats “slaughter-based” might seem provocative to some, but it’s probably about as fair as calling new meats “lab-based.” If we can avoid slaughter, after all, we should. If we can heat our homes without overheating the planet, we should. If we can grow more resilient and productive crops in a changing climate, we should.

That’s not to say that there aren’t important caveats to new technology, or that it shouldn’t be regulated. Quite the opposite. But in challenging our preconceptions, be they physical or linguistic, new technologies can also lead us to think more precisely about the world we want to build for future generations. But that only happens if we resist pressure from special interests, consult scientists, and focus on finding solutions.