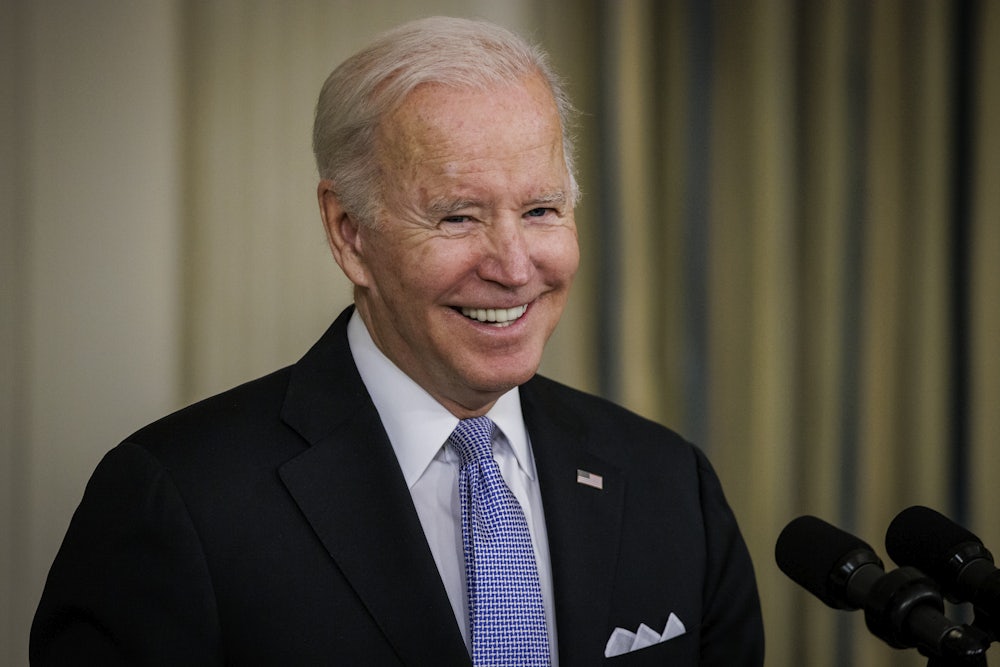

With less than a year until next year’s midterm elections, Democrats are in a tough spot. Yes, the party has just passed a $1 trillion infrastructure bill. But President Joe Biden’s popularity is underwater, and concerns about the economy have given Republicans a historic early polling advantage. None of this is being helped by the party’s continued failure to pass a budget reconciliation package that would contain many of the party’s 2020 campaign promises on green energy, childcare, and health care.

Eleven years ago, after months of wrangling and cuts, Democrats passed another messy, confusing bill: the Affordable Care Act. That bill wasn’t enough to save the party: Republicans won a staggering 63 House seats, in large part thanks to discontent over President Obama’s signature health care bill. The New Republic spoke with Indivisible co-founder Leah Greenberg, who was a congressional staffer in 2010, about what Democrats selling the Build Back Better Act in 2022 can learn from the party’s experience selling Obamacare in 2010.

Eleven years ago, the Democrats were also trying to sell a big, confusing bill: the Affordable Care Act. You were working for Tom Perriello then, a Democrat representing central and southern Virginia. How did selling that bill to voters work then?

When we went into 2010, there were a lot of reasons to be concerned. We were heading into a midterm election where the president’s party normally loses seats with an economy that was still staggering from the 2010 crash, high unemployment, a lot of suffering and people losing their homes, and a general sense that Washington had not been responsive to the crises that people were facing in their own life.

From my experience trying to sell the health care bill to voters, the problem was not that it had overreached. The problem was that they did not understand how it was going to impact their lives. Into that gap had come a large number of negative assumptions about the bill, the process of how it came about, and the fact that it hadn’t kicked in in ways that were benefiting them yet.

When you were talking to voters in the lead-up to the 2010 midterms, what kind of problems did you encounter?

What was challenging was that when the Affordable Care Act was passed, it was a messy and complicated bill. Some of the most popular benefits were not going to kick in for an extended period of time. I’m thinking particularly of Medicaid expansions, which, in order to maintain a certain price tag for the bill, were scheduled to come in years later. Having conversations with voters about what this bill actually did for them was incredibly complicated. You could point to the preexisting conditions language. That was helpful. But it was swamped by people’s vague sense that something about mandates was coming. We didn’t see death panels as being a particularly dominant theme among actually gettable voters. But people certainly had a general sense that there was a lot of red tape, possibly some kind of financial penalty in the future. It had not solved their particular problems or particular concerns about health care’s affordability or accessibility or the sense that they had a real social safety net under them. It was really, really difficult because of the way that the bill was constructed to actually have that conversation with a voter.

After the bill was passed, the response from a lot of Democrats was to run away from the bill and barely talk about it, if at all, on the trail.

That was the advice! There was polling being circulated saying the best thing to do, whether you voted for the ACA or you didn’t, was just to not talk about the Affordable Care Act. There is an enormous collective action problem there. The perception of a number of moderate to conservative Democrats at the time, both during the negotiation of the bill and after its passage, was that their best play was to distinguish themselves from other Democrats by being publicly critical of the bill. The reality is that it’s possible that you can eke out a little bit of a benefit at the margin, but by far the thing that dragged everyone with a D next to their name down was the negative perception of the bill. Had Democrats been able to move any form of the bill forward three months earlier, four months earlier, and then actually dedicated themselves as a party to selling it, you would have headed into 2010 in a radically different place. That would have had implications for everyone, whether they voted for it or against it.

Moving to the Build Back Better Act, Democrats seem to be having a hard time explaining the bill, in part because there’s so much unrelated stuff in it.

There’s a lot in the bill that will sell itself. But I think there are also certain structural challenges that have impeded it. A big part of the problem is the commitment to reconciliation. You can imagine a world with a functional legislative system where we were passing a universal pre-K bill and then we were passing a massive green energy investment bill and then we were passing a making childcare affordable bill and then we were passing a prescription drug reform bill. Then, every couple of weeks you have headlines about something popular and exciting, and the headlines are about something substantive that we’re actually doing about it. That is one of the asymmetrical ways that the filibuster hurts Democrats: It forces us to take all of our popular things, try to put them together, try to make them all harmonize with each other, in one single package. Meanwhile, everyone who has a reason to oppose any one of those things tries to come for the package.

That’s a very challenging place to be, to begin with. And that’s before we even get to the stuff that can’t be reconciled!

One thing that seems to be dragging Democrats down is that people don’t seem to know what’s in the bill because it took so long for congressional Democrats to decide what’s in it—a process that is still ongoing. How significant is that?

Until we have clarity on what is going to be in the final package, there are going to be ongoing debates about what’s in and what’s out. What the public hears is, every week, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema declaring that another enormously popular thing is out of the package—which is not the greatest overall messaging phrase! People are hearing a lot more about what we can’t have than what we can have right now. That will switch once the bill is passed, which is why it’s important to pass it as fast as possible and pivot to making sure people understand what is so exciting about it and what will change their lives. Conservative Democrats’ insistence on dragging this process out for several months and this constant drip-drip-drip of cutting popular things out of the bill has been a challenge.

As in 2010, there’s a sticker-shock issue here, with many raising concerns about the size and scope of the bill.

Well that’s certainly what they are saying. We should be real: Folks who didn’t want to pass this bill for one reason six months ago are saying that they don’t want to pass it for another reason now. Hand-wringing over the deficit, hand-wringing over economic conditions—these are perennial parts of the debate over expanding the social safety net for people who are struggling. Most of the debates that we’ve experienced, and this was true during the Obama era too, about the deficit are ultimately a debate about the size, scope, and role of government in our lives. We should have that conversation. We should be talking about if we should have universal pre-K and how are we going to pay for it. And the way that we’re going to pay for it is to have the wealthy actually pay their fair share.

Do you think the “Democrats in disarray” framing fits what’s happening in Congress right now?

To some extent, this is a lesson that everyone has to keep learning over and over again. We have seen, at times, the Biden administration lean in and really focus on an aggressive economic message that is ultimately about how they’re going to deliver for everyone. Fundamentally, we have seen pretty consistently through this fight that this is not actually a fight between moderates and progressives. This is a fight between the vast majority of people in the Democratic Party who want to deliver on the Biden agenda and a relatively small [number of] people who perceive an advantage, either electoral or financial, derailing it, in whole or in part. I think it’s a mistake to frame this as an ideological battle. Pretty consistently what the progressive side of the aisle has been trying to do is maximize the extent to which we’re delivering on the Biden agenda. And pretty consistently the objections that we’re hearing from the relatively small faction of obstructionists have been objections to what are often the most popular parts of the bill. We shouldn’t mince words about what’s happening: This is about the concerns of corporate interests.

How important is timing?

A lot of the conversation about what the Affordable Care Act would do for you in 2010 was about a few years in the future. What we pretty consistently see is that it’s better to give people something that they like and then tell them that they need to defend it rather than to tell people that something will roll out a few years later. That’s one of the reasons why we’ve really focused on what can be tangible, what can be delivered for the maximum number of people as early as possible. No message is going to be as strong as actually making a difference in someone’s life before the midterms.

Do you think that this bill has the opportunity to do that in a way that the ACA did not?

You have the child tax credit expansion. You have childcare and pre-K kicking in right away, especially for the lowest-income families. You have some places where there are real and tangible benefits if we act now.

There is really wide consensus across the Democratic Party this this is a good bill, that it should be passed, and that it contains things that Democrats running in 2022 will be really really proud to run on and will get a real advantage out of. The critiques that people across the spectrum have about messaging are actually pretty broadly shared.

Fundamentally, I think what we should all keep front and center is that the reason that we’re still in November and debating how to get this across the finish line, the reason that you have had a raft of headlines about the things we can’t have about the bill rather than the exciting, cool things that we are going to deliver for people—that reflects the ongoing obstruction from a relatively small number of conservative holdouts who have not demonstrated that they are ultimately invested in getting to an outcome.